Wheat F.O.O.D: Meet The Dough Boys

What you are really eating when you bite a loaf of bread

Last year, a paper from University of Michigan researchers presented a surprising discovery from the medieval Nigerian city of Ile-Ife: archaeological evidence of wheat. This finding was unexpected, as the humid climate of southwestern Nigeria has always been considered inhospitable to wheat cultivation. The team unearthed 48 grains of free-threshing wheat from the 13th and 14th centuries. Their analysis concluded that the wheat was not a local crop but an imported prestige good, a theory bolstered by the site’s humid forest environment and the lack of any waste materials associated with threshing or processing local harvests.

Unaware of this ancient precedent, the British began their own experiments with wheat cultivation in Nigeria during the early 1900s. Recognising the climate posed a significant challenge, they concentrated their efforts in the cooler northern regions. The results were mixed: while a variety known as “Kano wheat” proved to be of excellent quality for milling and baking, other types imported from India saw only limited success. The ultimate failure of these ventures, however, would be laid bare by the outbreak of the Second World War, which severely disrupted food imports and exposed the fragility of such agricultural schemes.

The Bread King

Amos Stanley Wynter Shackleford was born in 1887 in Charles Town, Jamaica. A bright and academically gifted child from a family with no history of bread-making, he began his career at sixteen with the Jamaican Government Railway. He held a variety of posts until 1912, when a fortuitous opportunity arose: the Nigerian Government Railways was conducting a recruitment programme in Jamaica. Inspired by his Maroon heritage and the early Pan-Africanist ideas of Marcus Garvey, Shackleford seized the chance. By 1913, he had taken up a new post in Colonial Nigeria where he started as a station clerk in Ebute-Metta.

While the British were conducting their wheat experiments in northern Nigeria, Shackleford and his wife, Catherine Rickets - the daughter of a Jamaican Baptist missionary - identified a growing market opportunity. Though bread was still a novelty in the local diet, its popularity was increasing. The couple consequently established a small bakery within their Ebute-Metta community in Lagos, founding what was effectively Nigeria’s first commercial bakery. Shackleford soon confronted the same problem that had plagued the British: a lack of locally sourced wheat. He circumvented this by importing wheat flour directly and then devising methods to stretch the expensive imported ingredient as far as possible.

Shackleford pioneered two key innovations: mechanisation and new distribution networks. In the early 1920s, he revolutionised local baking by importing a dough-brake machine, which mechanised the kneading process. This drastically increased his bakery’s efficiency and output, helping to offset the price of imported flour. Furthermore, he refused to rely on a passive customer base. Instead, he used vans and buses to deliver his soft, fluffy loaves - celebrated for their fresh, sweet taste - from Ebute Metta to areas like Agege, creating demand where little had existed before. Thanks to these strategies, his operations expanded beyond Lagos to other Nigerian towns and into the Gold Coast (modern Ghana) by the 1930s. His enterprise had effectively created a bread culture in southern Nigeria where one barely existed before.

The reliance on imported wheat was a structural, not a temporary, feature of the Nigerian market, a truth thrown into sharp relief during World War II. When naval blockades severed supply lines, the colonial government desperately launched campaigns to boost local wheat production, yet these efforts failed completely. By 1941, the Food Controller admitted that domestic harvests had “fallen far short of the demand,” forcing a reliance on scarce imports. It was within this enduring reality of dependence that Shackleford operated; his genius lay in navigating it with superior efficiency. By mechanising his bakery and diversifying his business interests, he built a resilient operation that could withstand the shortages which had confounded the colonial authorities, ensuring his bread remained a staple despite its imported origins.

His bread became a sensation so widespread that “Shackleton” - or as Lagosians of the time likely pronounced it, “Shakutin” - became a local synonym for bread itself. This legacy endures through the story of Agege bread. In the early 1960s, one of his former associates, Alhaji Ayokunnu, established his own venture in the Agege area, acquiring the same type of dough-kneading machine that Shackleford had pioneered. The bread he produced - characterised by its soft, springy texture, square loaf shape, and unsliced presentation - grew immensely popular, and people naturally began calling it Agege Bread, an enduring name that remains to this day.

A success story

Were it not for the brain melting effect that the cult of import substitution has had on Nigeria (fuelled in large part by the unfortunate success that Aliko Dangote has reaped from it in recent times), a story like this would be told as one of the biggest success stories of modern Nigeria. A foreign raw material was imported to create a uniquely Nigerian finished product, consumed nationwide. The proof of its triumph is its global reach. The same Agege bread - with its springy texture and unsliced presentation - that I could buy in Lagos is available just fifteen minutes from my home in Hertfordshire. Crucially, the loaves here aren’t imported from Nigeria; they are baked locally using the process knowledge perfected in Nigeria a century ago. That is the real export: not the bread, but the blueprint. And its name is still Agege bread.

The Turning Point

Up until very recently, things were relatively normal with getting wheat into Nigeria. There were no import bans, no additional levies and no FX restrictions on wheat imports into Nigeria. This pragmatic approach was soon overturned by powerful domestic lobbies, whose protectionist agenda found a willing ally in President Muhammadu Buhari. From around 2016, “Supplementary Protection Measures” (SPM) began to be implemented alongside the existing ECOWAS Common External Tariff (CET). This worked out at 5% duties plus 15% Import Adjust tax (IAT) for a total of 20%. By 2023, these levies were ramped up to 20% duties and 50% on IAT on wheat flour. A couple of years before, embracing this cause with fervour, Buhari was advocating for the empirically absurd goal of ending wheat importation by 2023.

What might possess a country to slap punitive import tariffs on a raw material it is not able to produce and which goes into producing a basic food item that millions of people rely on? It only makes sense once you understand that in the F.O.O.D scaffolding, tariffs are there for connected people to work around and create very tasty profits for themselves.

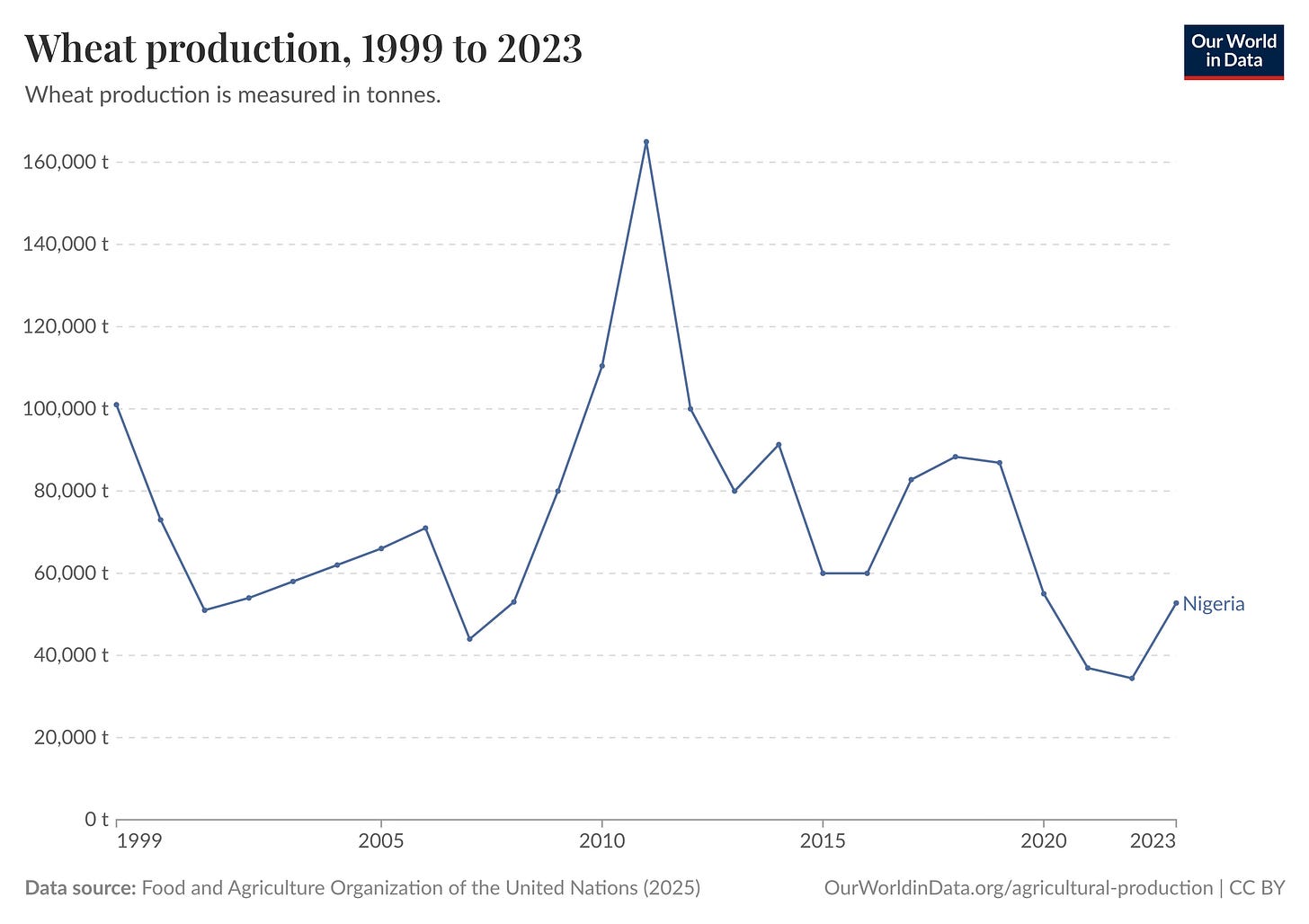

According to the latest report from the United States Department of Agriculture, Nigeria’s domestic wheat production is projected to be a mere 135,000 metric tons (MT) for the 2024/25 season. This figure is dwarfed by a total domestic consumption of 5.6 million MT, that several years after tariffs began to be imposed on wheat imports, local production meets just 2.4% of national demand. Approximately 70% of this demand is for bread production, with the remainder allocated to biscuits, cakes, and other wheat-based foods - implying that practically all of it is destined for human consumption.

Other data sources like the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) put domestic wheat production even lower:

In Nigeria, the imposition of a tariff is invariably accompanied by a system of waivers, creating a protected class of businesses that profit from preferential treatment. A select group of firms - Flour Mills of Nigeria, Olam International, and BUA Foods (hereafter, The Dough Boys) - are the beneficiaries of this particular F.O.O.D. Collectively controlling over 85% of the country’s wheat imports (PDF, page 28), they are exempt from paying these tariffs under the designation of “millers.” This allows them to operate from a position of privilege while pricing their goods as if they bore the full cost of the levies.

Checking in on The Dough Boys

To see the impact of what has happened especially since 2023, let’s step through some workings and charts.

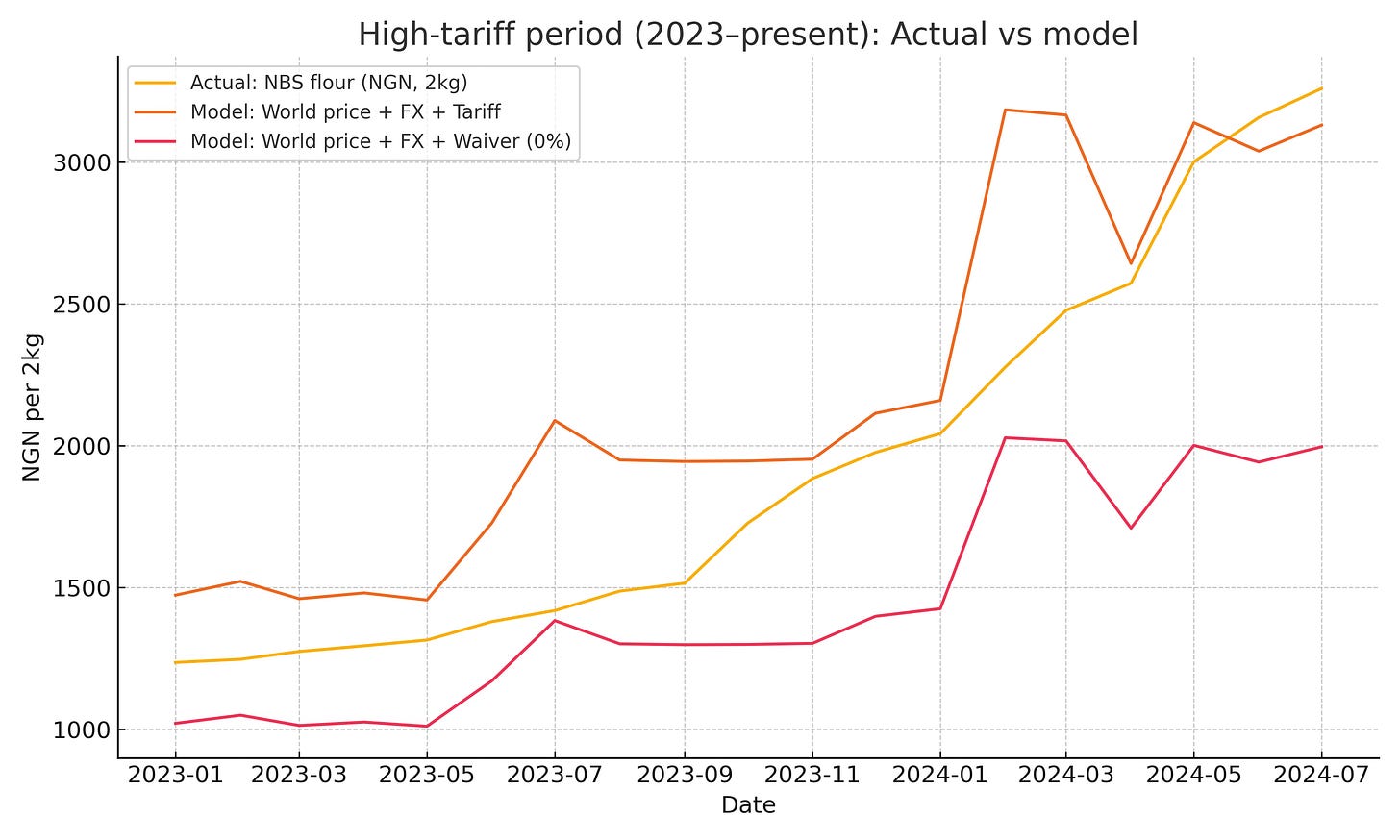

The main point I want to check here is this - since The Dough Boys get waivers on the high tariffs, what will it look like if we track local prices compared with international prices plus tariffs and international prices without tariffs?

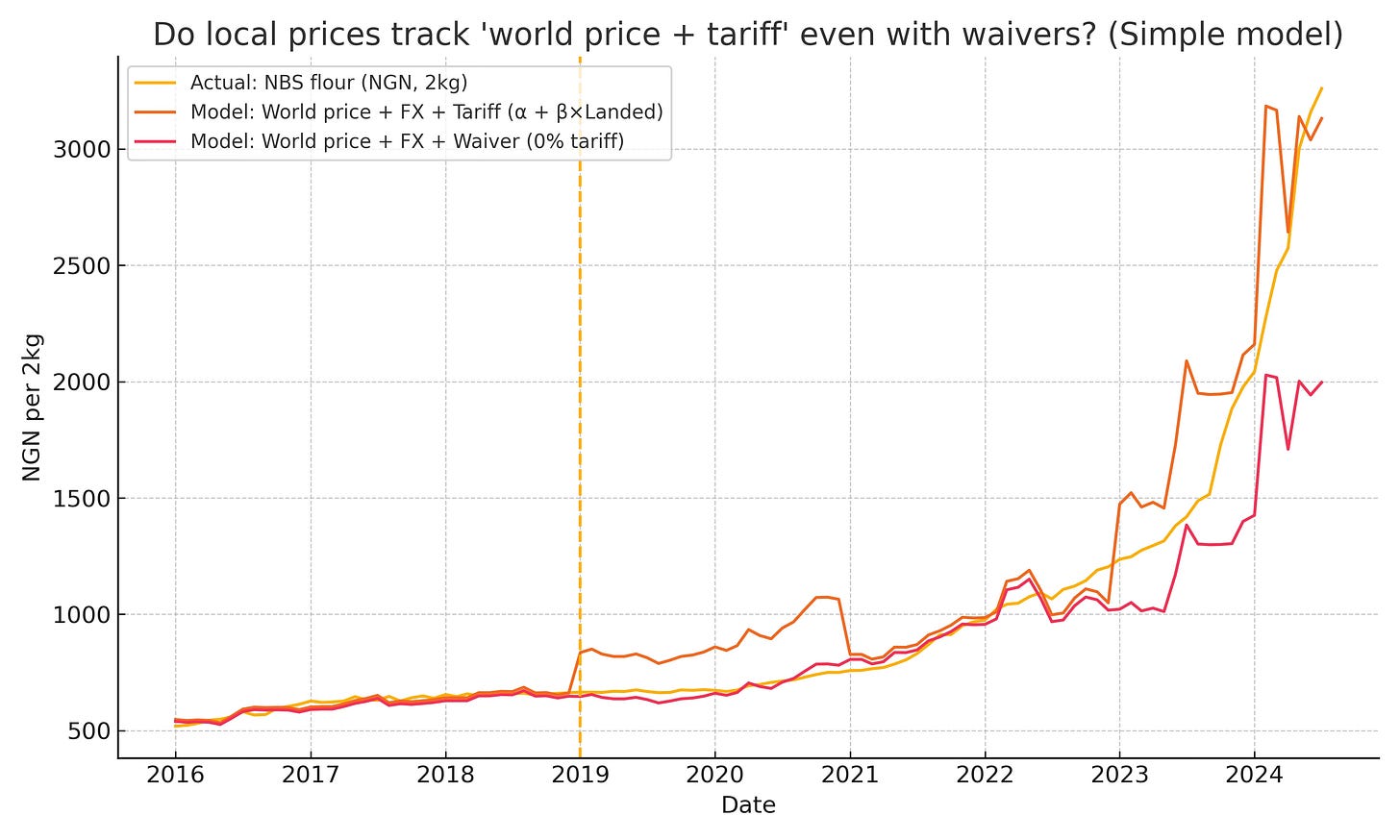

To model the relationship between global wheat prices and local flour costs, I have used the following transparent assumptions. The international benchmark is the U.S. Hard Red Winter wheat price from the World Bank Pink Sheet, while the local price is the NBS data for a 2kg bag of Golden Penny flour (available from January 2016 to date.) I converted U.S. dollars to Nigerian Naira using the monthly average of the CBN’s official exchange rate (since The Dough Boys would have gotten access to official rates before May 2023’s liberalisation.) For policy, I assumed tariff changes take effect at the start of a calendar year, applying a 5% rate for 2016-2018 and 2021-2022, and a 70% rate for 2019-2020 (there was a stop and start in the tariffs in this period) and from 2023 onward. A constant freight cost of $70 per metric ton was used. To convert raw wheat to flour, I applied a standard milling yield of 75%, meaning 2.667 kg of wheat is needed to produce 2 kg of flour. The tariff is applied to the combined cost of wheat and freight. You can inspect my underlying data here.

When we look at the result of the model for this high tariff period from 2023, here’s what we see1:

This case exposes the central point I stated at the start of the F.O.O.D series: the beneficiaries of tariff waivers simply pocket the difference, charging consumers as if they had paid the full, punitive levy. The introduction of tariffs means that we now have two prices for the same product and so we can check in to see which of these two prices the local price follows.

The chart above shows it plainly. The dark red line shows where prices should be if the waivers received by The Dough Boys were passed on to Nigerian consumers. Instead, the actual price of Golden Penny tracks ruthlessly against the far higher orange line - the world price converted at CBN exchange rates plus the 70% tariff. The result is a price that is artificially inflated by roughly 50%. Of all the F.O.O.D case studies we’ve examined, this is the one that has irritated and disgusted me the most. A government that knowingly orchestrates such a fleecing of its own hungry citizens has forfeited its fundamental reason to exist.

We can buttress the point by stretching the chart back out to 2016 where the NBS data series starts. Before tariffs started, Nigerians simply paid the international price of wheat, which is what you’d expect for a wholly imported raw material. Once the tariffs started, we start to see the link between international and local prices broken. It is perhaps telling that Olam bought Dangote Flour in 2019, to get into the tariff game.

Inside the accounts

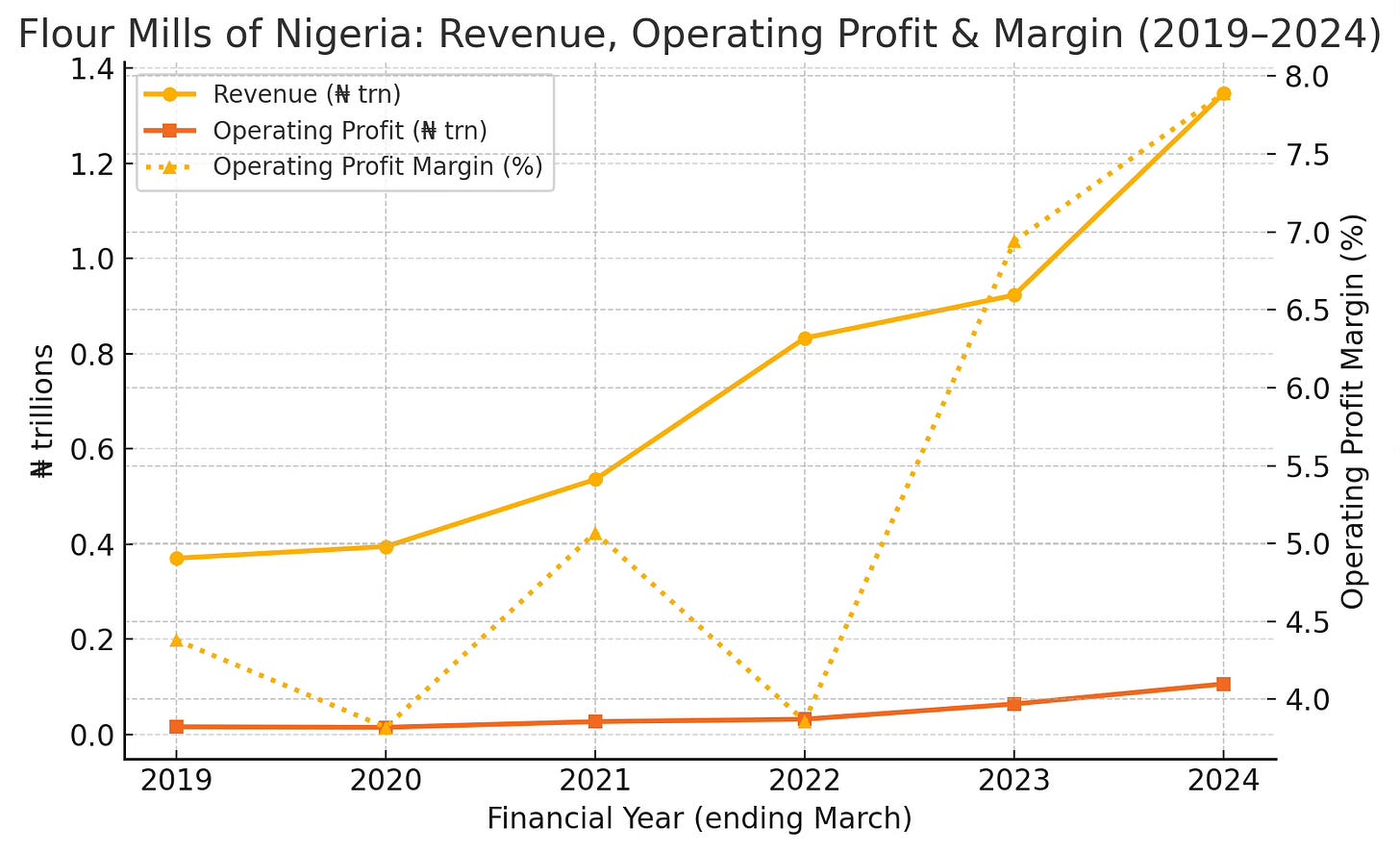

To assess the impact of the tariffs, I examined the financial accounts of Flour Mills of Nigeria (the standalone company, not the Group) from 2019 onward. It is worth noting that a comparable analysis for Olam was not possible, as its accounts do not appear to be publicly available.

Here’s what it looks like:

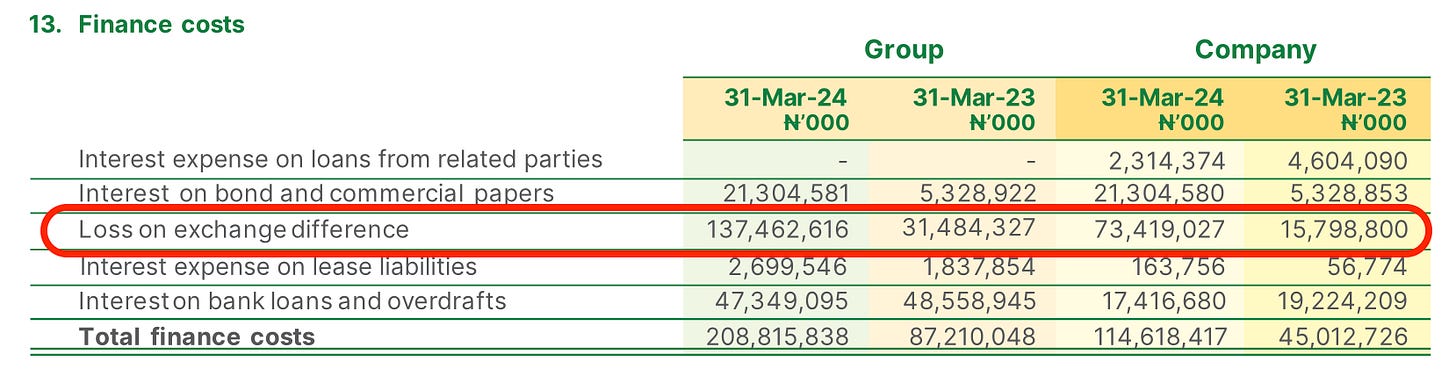

While massive naira devaluation in 2023 complicates the revenue analysis, the operating profit margin provides a clearer picture: it has climbed from 4.38% in 2019 to 7.89% in 2024. Equally telling is a change in the accounts themselves. As the tariff regime effectively anointed its beneficiaries as primary importers, a new financial line item appeared in Flour Mills’ 2024 report, with prior-year figures restated for comparison - a direct reflection of their transformed role as designated flour importers:

I did the same thing for BUA using the segment numbers for flour. These are only available publicly going back to 2021. The operating profit numbers are before depreciation and impairment so a cleaner measure. Here’s what it looks like:

Operating margins contracted from 12.04% in 2021 to 8.62% in 2022, only to surge dramatically to 23.3% in 2023 and then 34.36% in 2024. It is essential to contextualise these figures: these are the profit margins on a staple food product, one that the company imports tariff-free, yet sells to the Nigerian public at prices that fully incorporate the avoided levy.

Conclusion

Given that a significant amount of sugar goes into the making of bread, when you combine the shenanigans of the Sugar Babies we covered in the previous instalment to the work of The Dough Boys in this post, It is no exaggeration to say that with every bite of bread, a Nigerian consumer is swallowing a heavy dose of tariffs - whether actually paid or simply priced in as pure profit for a privileged few. The true ingredient in the modern Nigerian loaf is artificial cost.

Reducing the cost of food for Nigerians by abolishing this unnecessary tariff is one of the most straightforward policy decisions available to any government. The notion that local milling is contingent on such punitive protection is an admission of inefficiency; those who hold this view should be directed to other ventures. Given that Nigeria will never be a significant wheat producer, the national priority must be to secure this vital food input as cheaply as possible. This is not a complex economic puzzle but a simple matter of common sense - it is, quite plainly, the right thing to do.

Ultimately, a nation’s policies should make bread cheaper for its people, not more profitable for a select few. Thankfully this is a very recent policy that can still be changed before it becomes too entrenched.

A simplified example of this model: say US HRW price for the month was $250/MT. I add freight costs of say $40 to give a price of $290/MT. The prevailing tariff in that month was 70% so when I add this I get to $493/MT. If the exchange rate in that month was N500/$1 this gives us N246,500/MT. With a milling yield of 75%, we get N328,666/tonne of flour (N246,500/0.75). To get the per bag price of flour in Nigeria we take this tonne, divide it by 1000 and multiply it by 2 to arrive at the price of a 2kg bag of Golden Penny: N328,666/1000 * 2 = N657 i.e what the price should be with 70% tariffs included. We can then check this against the actual NBS price.

With every new article in this F.O.O.D series I'm left feeling disgusted than the last time. A profit margin of 36% on a staple product that is imported tariff free is beyond criminal. Nigerians are being starved just so a few people can benefit immensely. Like you said, a government that allows this has lost its raison d'etre.

Best post ever! 😂 Charles Town Maroons very distinct group of Maroons and are alive and well with an annual festival. They would greatly appreciate this story so shall look for a link. In general, the fascinating story of Black Jamaican returnees (usually missionaries) not widely known though a few books exist. Black Baptists active also in Ghana and Western Cameroon from early 19th C.. Interesting point here is that not confined to religion. Thanks for this 👍👍