Sweet F.O.O.D: Meet The Sugar Babies

The Nigerian sugar industry will leave a bitter taste in your mouth

This case study begins not with a story, but with a long-held hypothesis of mine: because traditional Nigerian cuisine is not defined by sugary flavours, sweetness has always existed at the periphery of the diet. Everyday staples - from yam and cassava to plantains, beans, and rice - are overwhelmingly starchy, savoury, or spicy, historically prepared with minimal sweeteners. Unlike many Western culinary traditions, there is no deeply ingrained custom of sugary desserts to conclude a meal, nor have sugar-laden baked goods like cakes ever been a central part of Nigeria’s food heritage.

Historically, the Nigerian diet derived its energy from complex carbohydrates and fats, such as palm oil and groundnuts, with refined sugar being a relative scarcity. Even as colonial trade made it more accessible, sugar first entered the territory as a luxury - in Professor Anthony Hopkins Capitalism in the Colonies which Tobi and I read along on this site last year, sugar regularly pops up as one of the main imported goods in the pre-colonial era, coming in from Europe and Brazil. Its eventual transition to a daily commodity did little to alter the fundamental character of the main meals, which remained steadfastly savoury. Consequently, sweetness found its niche outside the core meal in snacks, beverages, and other accompaniments. This legacy persists today, where a bottle of soda often serves as the quintessential “dessert.” An amusing expression of this can be found outside of Nigeria where Nigerian coca-cola is marketed as “a perfect accompaniment to any meal, especially with spicy and savoury dishes where its sweetness provides a delightful contrast.”

One might wryly observe that Western diets, with sugar so thoroughly integrated, require their own parallel healthcare systems - a luxury Nigeria can scarcely afford. My hypothesis, however, points to a more fundamental human truth: where a natural taste for sweetness is not met within the core meal, people will inevitably find alternatives to compensate. This offers a plausible explanation for the popularity of intensely sweet beverages in Nigeria; they effectively “fill the gap” left by a diet traditionally low in sweet flavours.

Thinking of a Master Plan

Within the F.O.O.D. scaffolding, once a demonstrable need is identified among Nigerians, it inevitably becomes a target for a particular kind of “entrepreneur.” In the case of sugar, this dynamic played out precisely. Following extensive lobbying that highlighted how Nigeria produced a mere 3% of its domestic sugar consumption - an import dependency draining an estimated N100 billion in foreign exchange annually - the government approved the National Sugar Master Plan (NSMP) in late 2012. The government projected it would save $350 million in forex yearly and create about 37,000 permanent jobs by reviving the sugar value chain over the ten year life of the NSMP.

The NSMP gave rise to the Sugar Backward Integration Programme (BIP), an initiative designed to achieve national self-sufficiency in sugar production. Its goal was to meet Nigeria’s annual demand of roughly 1.7 million metric tonnes by 2020 - a deadline since extended for obvious reasons. The programme also aimed to capitalize on by-products like ethanol to support energy generation. The first major policy action under the BIP arrived in January 2013, with a sharp increase in import duties on foreign sugar: a 10% duty plus a 50% levy was applied to raw sugar, while refined sugar faced a 20% duty and a 60% levy. The importation of packaged refined sugar was banned outright. The initial plan was quite ambitious with a plan to ban all types of sugar imports - raw or refined - by 2015. That has since been extended to 2033.

It went further. Somewhat unusually, the BIP established a system of import quotas for raw sugar, directly tying them to local investment. In essence, only pre-approved operators committed to backward-integration projects were permitted to import raw sugar for refining. Their allotted quota was proportional to their refining capacity and their demonstrated progress in cultivating domestic sugar plantations. This created a clear mandate for all importers: to maintain their licences, they had to own or develop local sugar farms - a definitive “grow cane domestically or lose your import rights” policy.

To further encourage investment in local sugar production, the government introduced a suite of fiscal incentives. These included a five-year tax holiday for investors across the sugar value chain and a zero-percent import duty on machinery and equipment for sugar projects. Concessionary loan facilities were arranged, and a dedicated Sugar Development Fund was established under the National Sugar Development Council - financed partly by levies on sugar imports - to support investors. According to the Bank of Industry, which manages the disbursement of the fund, loans are arranged at a very concessionary 5% (PDF, page 103).The strategy was: by reducing upfront capital costs and improving long-term project viability, these incentives were designed to make the substantial investments in plantations and refining mills far more attractive.

A further unconventional aspect of this policy was the government’s explicit designation of three specific companies to drive its implementation. In effect, the strategy was crafted primarily for, and around, these established market leaders: our old friend, Aliko Dangote’s Dangote Sugar Refinery, Abdulsamad Rabiu’s BUA Sugar, and the Golden Sugar Company, a subsidiary of Flour Mills of Nigeria - hereafter referred to as the Sugar Babies. Collectively controlling nearly the entire sugar market, these three were granted exclusive import quota licences - a status only recently challenged by a new entrant, Kia Africa. This exclusivity was then consolidated in 2021 when the Central Bank of Nigeria, under the marauding Governor Godwin Emefiele, intervened to decree that only these same three firms could access official foreign exchange rates for sugar imports. The value of these tariff quotas and concessions was substantial, estimated at N170 billion as early as 2019, with Dangote Sugar alone capturing N102 billion of that total.

Other side of the ledger

The substantial support and incentives granted to the designated sugar producers raises the question: what have they delivered in return? To answer this, we must examine the practical consequences of this policy.

A key outcome of the import licence regime was that any manufacturer requiring a specialised grade of sugar unavailable locally - a beverage or juice producer, for instance - was forced to petition one of the three major firms to import it on their behalf. This is not a hypothetical scenario but a documented operational reality, effectively transforming the purported domestic manufacturers into national importers in all but name. Furthermore, because import quotas were directly linked to their reported progress in local cultivation, the system created a perverse incentive to exaggerate the amount of land they had genuinely brought under sugarcane production. You can view the public data on the import quotas here.

Every year the United States Agricultural Department’s Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) publishes a report on sugar in Nigeria. The most recent one was published in April of this year and includes this paragraph:

FAS-Lagos estimates that Golden Sugar has planted sugarcane on about 5,000 hectares of the 15,000 of land available, Dangote has planted 6,000 of the 23,000 hectares available, and BUA Sugar has planted 5,000 of the 20,000 hectares available. Post estimates that Golden Sugar and Dangote are harvesting much of the planted hectares for further refining, however BUA is using much of the planted sugarcane to replant and expand and not using it to refine.

[…]

FAS-Lagos forecasts domestic sugar production at 105,000 MT in MY 2025/26, about a 31 percent increase compared to the previous year’s estimate (Table 2). The 31 percent increase does not indicate a significant increase in sugar production; rather, it is the result of increasing the estimate of sugarcane yields. According to contacts, only about 30 percent of sugarcane produced is refined into raw sugar, while the remaining 70 percent never enters refining. Post expects an increase in sugar production because of the expected increase in large-scale sugar company milling capacities and an improved sugar recovery rate.

The report puts the local demand for sugar at 1.5 million MT in 2024/25 meaning that the domestic production of 105,000 MT by the Sugar Babies currently meets about 7% of local demand. This is more than a decade after the NSMP came to life.

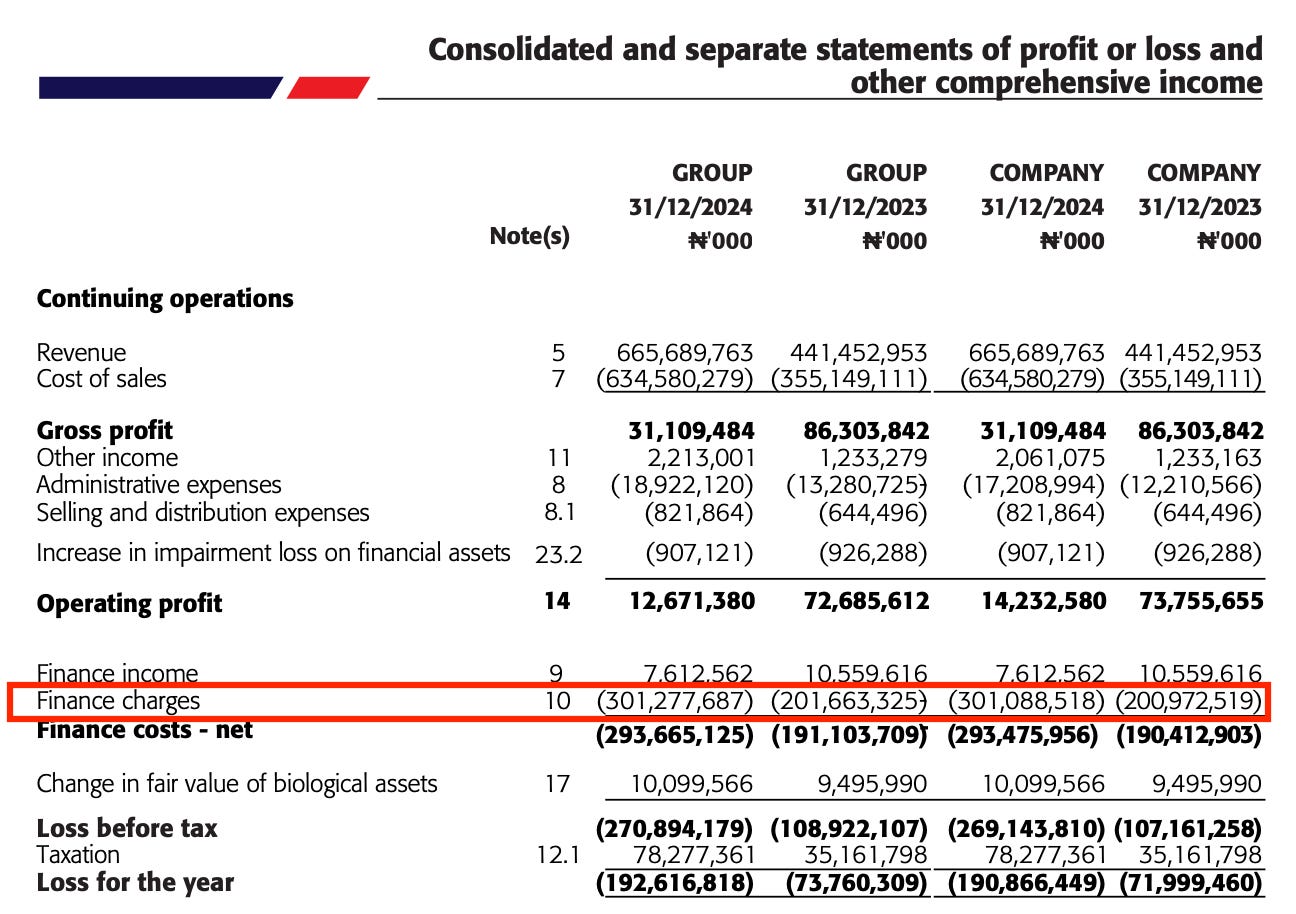

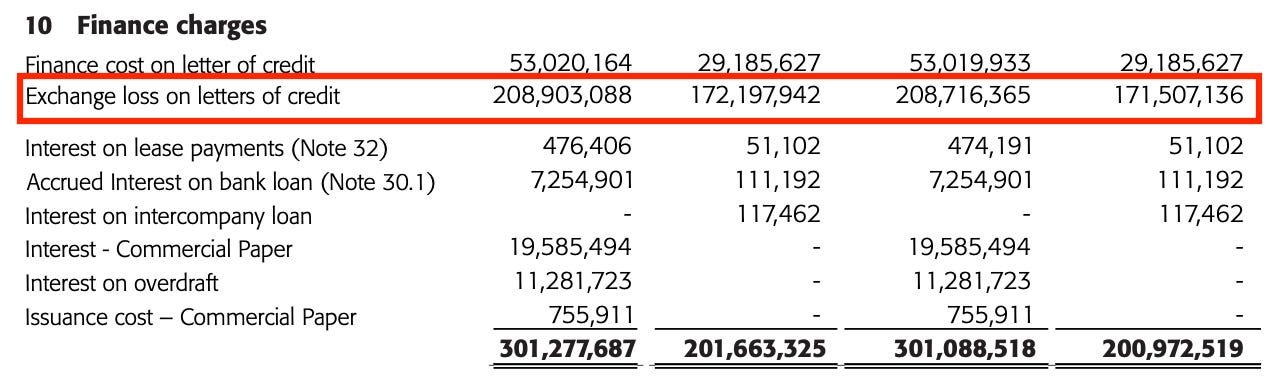

Maybe the Americans are lying? We can sense check the numbers against what the Sugar Babies themselves publish in their accounts. In the Dangote Sugar accounts for 2024, a massive N301 billion loss is attributed to finance charges. What’s that?

When you follow the accounts to Note 10 where this is broken down, you see this:

This loss is almost entirely attributed to “exchange loss on letters of credit.” The mechanism works like this: when Dangote Sugar needs to import raw sugar (primarily from Brazil, the source for most of Nigeria’s supply), it secures a letter of credit - a bank guarantee of payment in US dollars to the supplier. Dangote Sugar then allocates naira to cover this dollar commitment based on the exchange rate at the time the letter is opened. However, Nigeria experienced significant currency devaluations in 2023 and 2024, which occurred after the letters were issued but before the dollar payments were settled. The additional N208 billion represents the extra naira required to fulfil the dollar obligations at the new, weaker exchange rate.

A company whose primary business is genuinely centred on local cultivation and refining of cane should have no exposure to such devastating foreign exchange volatility that erased an entire year’s profits.

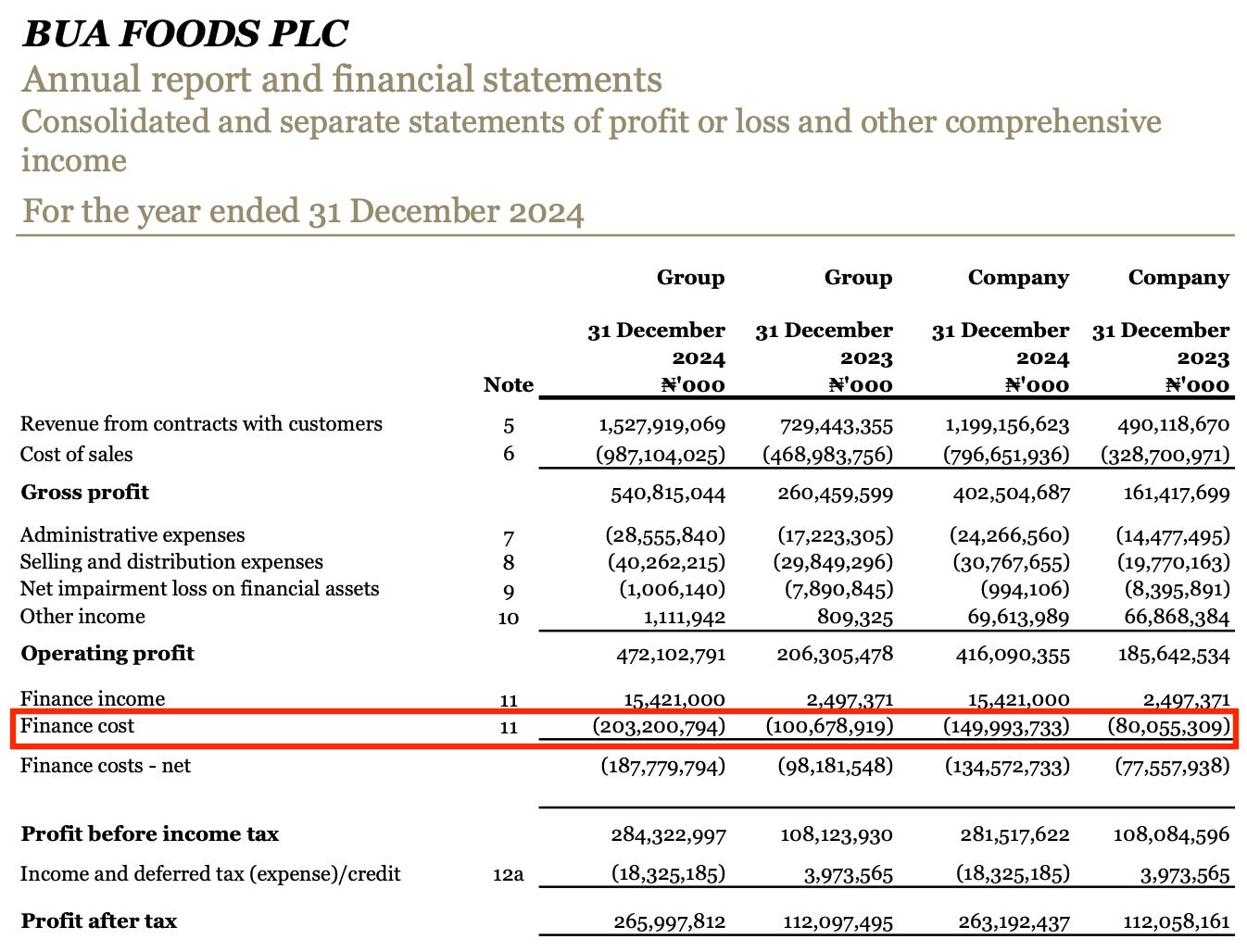

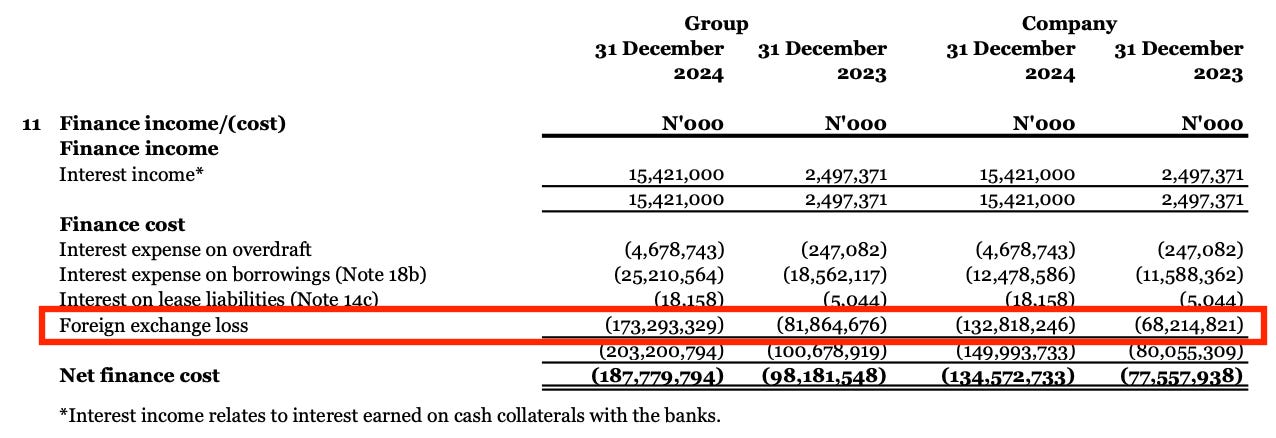

Something similar can be observed in the 2024 BUA Foods accounts (sugar sits inside the wider BUA foods business, not separately as with Dangote Sugar):

And when you drill down into Note 11, you see the same thing - FX losses making up almost all of that finance cost for the year:

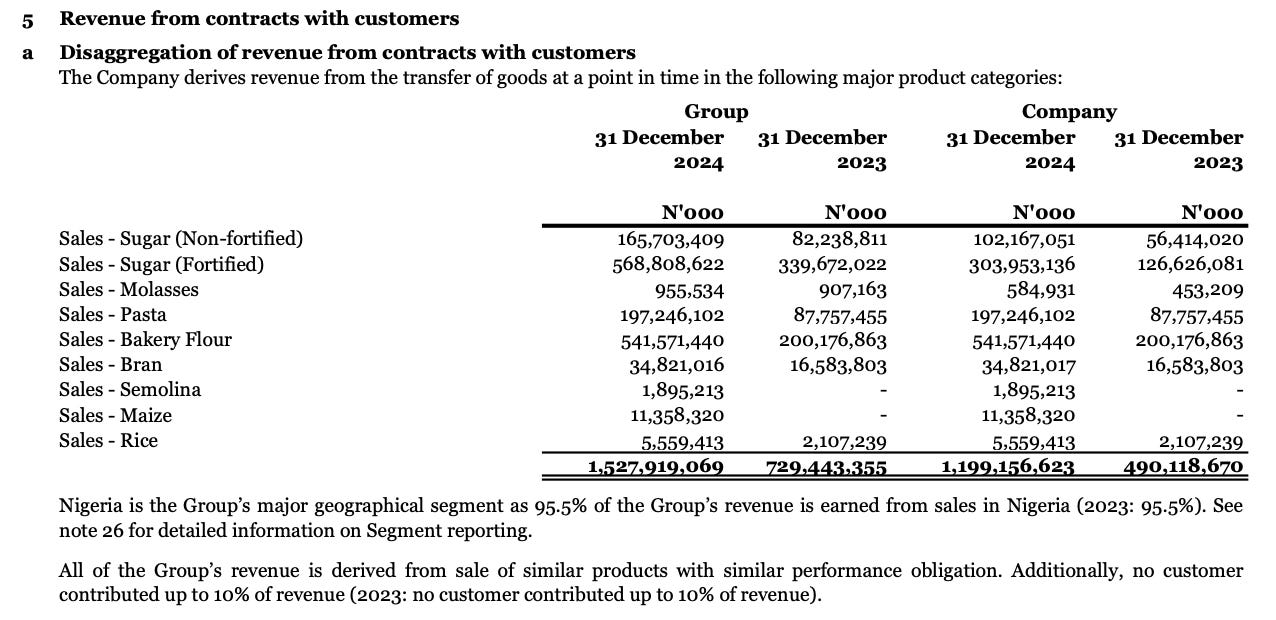

In BUA’s case however, it did not make a loss for the year because revenues doubled from N729 billion in 2023 to N1.5 trillion in 2024. How did it manage to do this? We go to Note 5:

It simply doubled prices on Nigerians, with sugar accounting for 40% of the increase in revenues from 2023 to 2024. Again, when prices of “locally manufactured” foods track FX devaluations in this way, it reveals something about what is actually going on. This is the inevitable outcome of a business model operating entirely behind a wall of government protection, insulated from competitive pressure. Such entities can operate with impunity.

Regarding Golden Sugar, anecdotal evidence - corroborated by the USDA report - suggests the company has made modest progress in actual cane cultivation and refining, somewhat outpacing its counterparts. However, this assessment must be contextualised against a very low bar. As Golden Sugar’s financial accounts are maintained separately from its parent company, Flour Mills of Nigeria, and are not publicly disclosed, a direct financial comparison like the one above is not feasible. While Flour Mills’ accounts indicate similar foreign exchange losses, these are primarily attributed to its flour operations - a related, yet distinct, narrative.

Instead, an amusing game that the Flour Mills likes to play is the repeated announcement of $500 million of “investments” into sugar refining which somehow never move the refining output needle. In 2009, before the NSMP, the company announced plans to invest $500 million in sugar refining in Nigeria. Last year, the company once again announced a $500 million investment in sugar refining in Niger state. Going forward, may I suggest they at least change the investment figure? (In 2013, a similar $500 million investment was announced by the company in cement production.)

In reality, these are little more than privileged importers disguised as “investors” making a purported contribution to the Nigerian economy through “backward integration.” When legislation is crafted specifically to serve your interests, this becomes the rational, if cynical, path of least resistance.

The Final Insult

The Nigerian sugar regulator - the mere existence of which is an absurdity in itself - used to publish a weekly summary report comparing the local and international prices of raw and white sugar (if you want a laugh about the sugar regulator, go to this link and observe how their expenditure jumped between 2016 and 2017.) In July 2023 it abruptly stopped publishing them and took down all the old versions of the report. The report used to sit at the location below on their website:

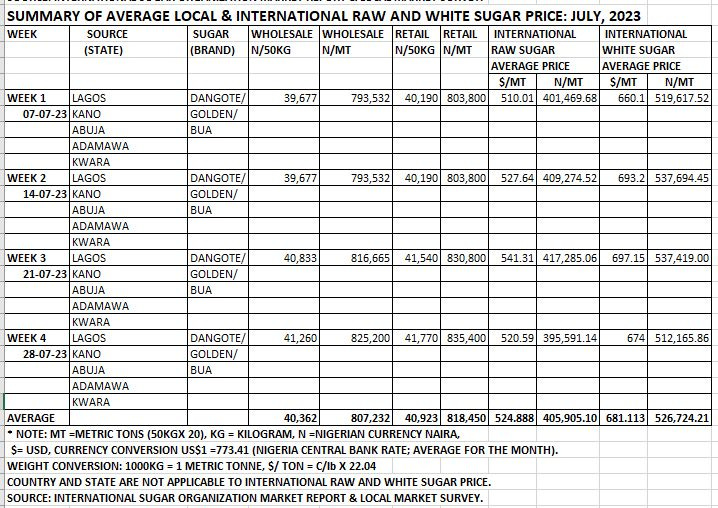

The link no longer shows anything when you click on it. What was in the report? Thankfully, a friend of mine who used to monitor them took a screen-grab of the last version of the report before it was taken down. Here’s what it looked like:

After lavishing them with tax breaks, shielding them from competition, and granting them exclusive access to foreign exchange and import licences, what did the nation receive from the Sugar Babies? They delivered a staggering result: domestic sugar prices that were double the international benchmark as of July 2023 - a situation unlikely to have improved. It is a scandal that the regulator has allowed this crucial data to go dark, and must be pressured immediately to restore accountability.

Conclusion

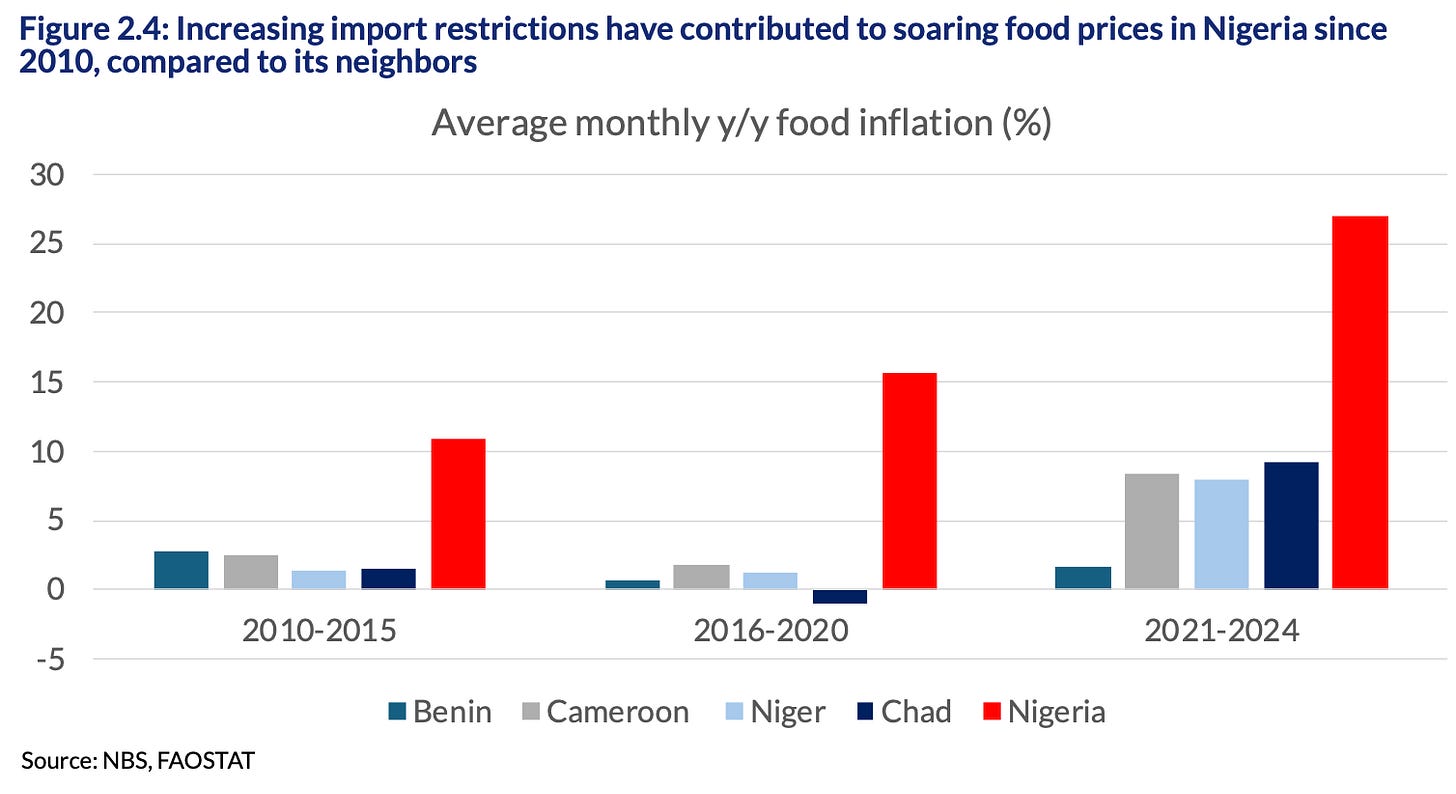

Yesterday the World Bank published its Nigerian Development Update (NDU) report. The section highlighting how import restrictions create distortions and concentration in the Nigerian economy is worth quoting extensively (emphasis mine):

These import restrictions aim to support domestic production but often undermine competition, encourage tax evasion, and drive up prices, as domestic production cannot meet demand. Trade barriers have contributed to narrow formal competition in rice, maize, and sorghum, shifting imports toward waivers-holders and informal channels. They have also led to undersupply, as with maize output, which repeatedly falls short of the demand from poultry and maize processing industries.

Finally, these policies have undermined productivity growth, with rice and maize missing yield targets, and the claimed self-sufficient sorghum recording declining yields and output (FAO, 2024). A few existing partial or complete import waivers are granted, but only to a handful of companies, further increasing market power. The three companies with import waivers for rice account for 96 percent of total imports, while the same number of companies concentrate 86 percent of wheat imports. For sugar, a single company concentrates 82 percent of all imports.

These effects of the import barriers ultimately result in higher food prices for Nigeria. Food inflation has been consistently much higher in Nigeria than in its neighbors, averaging around 10, 15, and 27 percent in 2010-2015, 2016-2020, and 2021-2024, respectively

These case studies are getting boring now. I could do several more and the F.O.O.D story will be the same. Too much of the Nigerian economy is distorted behind government protections that end up only protecting Nigerians from the chance of a better life. Behind these government protections are “entrepreneurs” in name only whose competitive nose and taste for innovation has been completely atrophied. It does not take a genius to see these problems and the damage they are doing. It does not need extra-strength glasses to see the sheer immiseration all around Nigeria, the result of an economy that fires on no cylinders.

More than a decade has passed since the full force of the state was mobilised to replace sugar imports with a domestic industry. The result? A litany of failure. No significant cultivation. No meaningful refining. No development of local technology. The anointed “investors” are little more than privileged importers, while Nigerians consume half the sugar of their African neighbours (if you follow this link on the sugar regulator’s website, you’ll see that sugar consumption has remained the same in more than a decade since the “master plan”.) The Sugar Babies reap obscene, undisturbed profits, as ordinary citizens are battered by an inflation driven by eye-watering prices - a direct consequence of the very “protection” meant to shield them. And then you get the government supposedly elected to better the lives of Nigerians tweeting about its commitment to maintaining stable sugar prices during Ramadan, ensuring affordability for Nigerians” as if it was powerless to do anything else.

On a personal and perhaps positive note, I have found a silver lining to this cloud. Having significantly reduced my own sugar intake over a year ago, the health benefits have been undeniable. By pricing sugar beyond the reach of so many, the Sugar Babies may have inadvertently launched the nation’s most effective - if entirely accidental - public health initiative.

One learns to accept progress, however unintentionally it is delivered.

When I saw ‘ the three sugar babies’, I already knew where this was going! Just despicable and deeply heartbreaking! For a non-economist and a non-scholar like me, I deeply appreciate this fantastic piece of writing and journalism. Also, how a piece of writing on sugar can get one this riled, must be one of those distinct ironies of life.😀 Thank you! And by the way, all these your friends giving you scoops are the real ‘MVPs’.

I wonder, with Alhaji pushing and fighting vehemently around crude refining in Nigeria, can we expect a similar FOOD report on petrol in 10-15 years?