F.O.O.D Is Ready

A framework for understanding how Nigeria's economy works and why it doesn't work

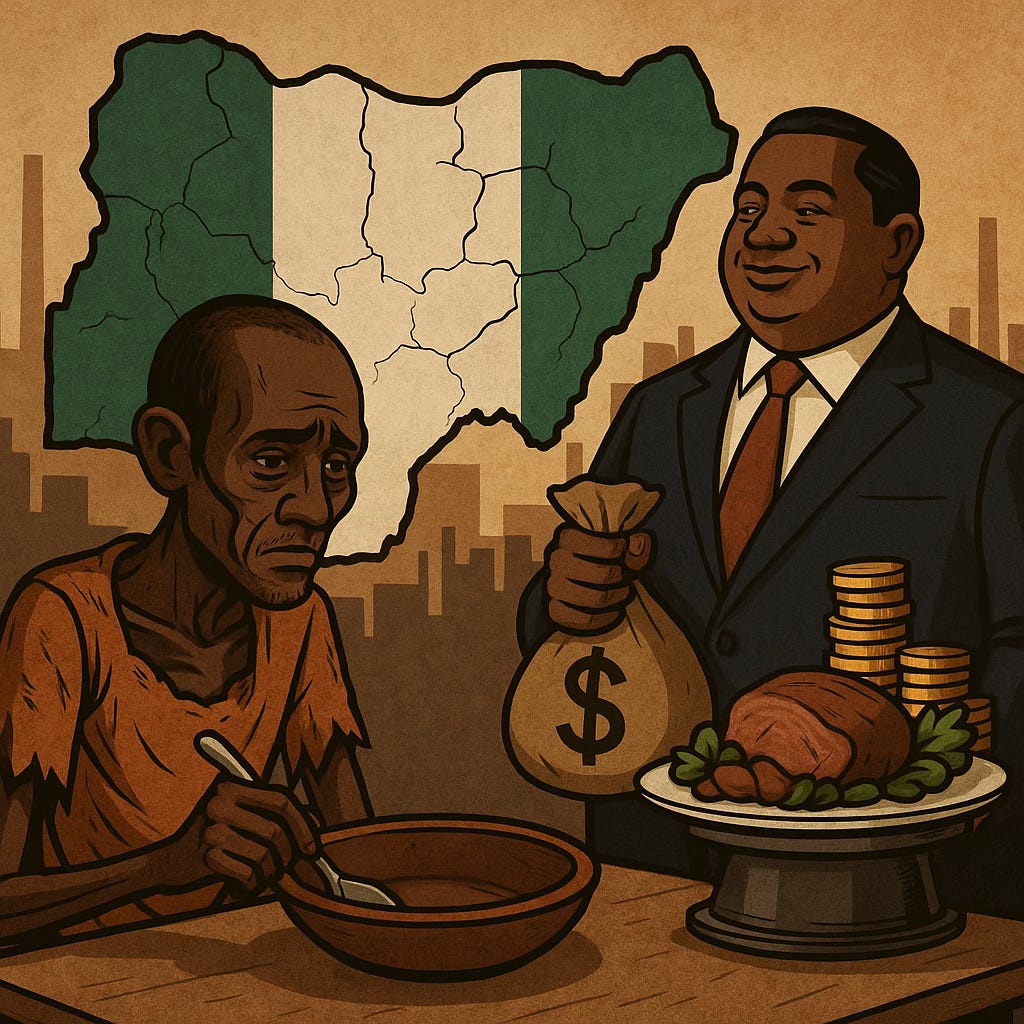

A stagnant economy - specifically the lack of innovation - is Nigeria's disease, and its richest men are the most prosperous symptom. They profit not by solving problems, but by profiting from them. To advance our discussion on this lack of innovation, I propose a framework to unpack this very paradox.

As a lowly accountant, not an academic, I offer this with the appropriate disclaimer: may I present, for your consideration, the Framework of Opportunity, Oligopoly, and Distortion. You can call it the F.O.O.D. framework - because if you follow the framework, you are guaranteed to eat well.

The framework unfolds something like this:

Someone somewhere outside of Nigeria comes up with an idea, innovation or invention

That idea, innovation or invention turns out to be something that Nigerians find useful because it solves an extant problem for them

Nigerians then begin to import a product that is the embodiment of that idea, innovation or invention, proving that there is a market for it in the country

At this point, the well connected Nigerian “entrepreneur” spots an “opportunity” and gets to work on “import substitution”

The case is made that this thing that was invented elsewhere and has proven to be a solution to a problem Nigerians had, is costing the nation “scarce foreign exchange” and “exporting jobs” while at the same time “importing poverty” (to be fair to the entrepreneur, Nigerians also fall for this argument and even amplify it themselves)

The “opportunity” is straightforward - since the thing being imported is already proven to have a market, the goal is to ban or tariff the imports while replacing it with your own “locally manufactured” version.

If all goes well (especially if the product is not easy to smuggle), you will make a lot of money because the price of the imported product plus the high tariffs you’ve lobbied government to place on them will determine the price of the local version of the product i.e. price of local version = price of foreign version + import tariffs and duties. In other words, Nigerians will see no benefit from the product being manufactured close to them at home other than some nebulous “foreign exchange savings” or local pride

The problem lies not just in the disease, but in the flawed cure. While import substitution is not itself a great crime, it becomes one when it is held up as the primary path to wealth. This creates a dangerous psychological signal: when the richest men profit from protectionism rather than innovation, they become the aspirational models for a generation. The result is a vicious cycle where this self-replicating behaviour stagnates the entire economy.

Case Study for F.O.O.D: BUA Foods Plc

A few weeks ago, Nigerian newspapers were awash with the news that BUA Foods Plc, owned by one of the nation’s richest men, Abdulsamad Rabiu, had become the most valuable listed company in the country by market capitalisation:

Market capitalisation of BUA Foods Plc, owned by Nigeria’s second richest man, Abdul Samad Rabiu, has soared to N10.3 trillion as of Friday, August 8, following an 8.7 percent rise in its share price to N574.9, making it the most valuable stock on the country’s bourse.

This historic feat came barely one week after the fast-moving consumer goods giant recorded the highest profit in six years, supported by a 36 percent rise in revenue to N913 billion and a stable naira that returned the manufacturer to FX gain after swimming in losses in the past year.

That is wonderful news, I hear you say, not least for the owner who pocketed an incredible N216 billion in dividends ($135 million) out of this performance (even though the company is “listed” on the Nigerian Stock Exchange, Abdulsamad Rabiu owns 95% of its shares, a story for another day)

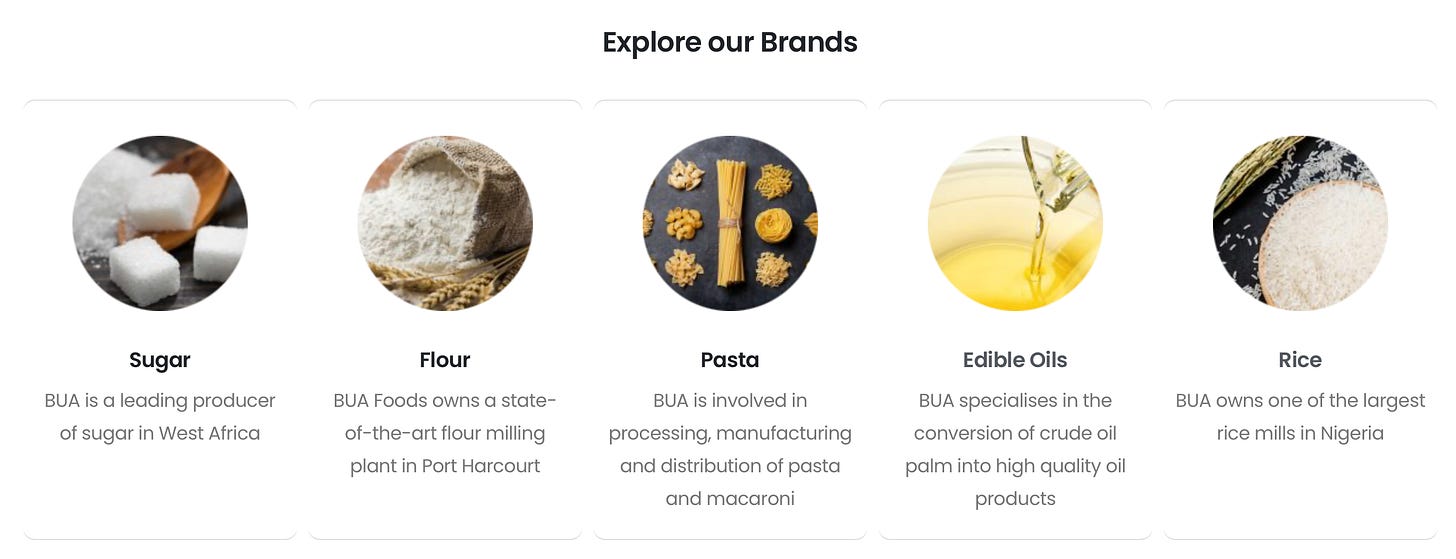

So what does this company actually do? Here, taken from the company’s own website, is a list of the products it sells:

This list is as much about what is on it as what is not on it. But let’s start with what is on there.

Sugar - sits behind up to 70% duties, made up of 10% import duties (ID) and 60% Import Adjustment Tax (IAT) plus VAT and you need a licence to import it. These tariffs apply to raw cane and refined sugar. Chapter 17 (PDF, page 71)

Flour - sits behind 70% duties (20% import duties plus 50% IAT) plus VAT. This applies to wheat and meslin flour and is an “improvement” from the previous 100% tariff. Chapter 11 (PDF, page 55)

Pasta - spaghetti and noodles are actually on the Nigerian Customs import prohibition list (number 7) i.e. they are banned. However on the tariff list, pasta sits behind 20% import duties plus VAT. Chapter 19 (PDF, page 76)

Edible Oils - These are palm and vegetable oils and they sit behind 10% import duties and 25% IAT for crude palm oil and other types of palm oils i.e. a total of 35% tariffs. Chapter 15 (PDF, page 65). Refined vegetable oils are on the banned list above (number 4).

Rice - semi-milled or wholly milled rice and broken rice sit behind 60% tariffs (10% import duties and 50% IAT) while brown rice sits behind 30% tariffs (10% import duties and 20% IAT). Chapter 9 (PDF, page 53).

This case study of BUA Foods perfectly illustrates the F.O.O.D. framework. The company has built a vast empire by only concerning itself with products shielded by heavy government tariffs. This strategy reveals everything: the real blueprint for their success is best understood by noting what is not on their product list - and why those unprotected goods will likely never be.

Consider the humble Nigerian yam. This is a product and sector desperately in need of innovation, plagued by endemic problems from planting to harvest. The scale of these challenges is vividly captured in an NPR report from a few years ago:

But in the past few years, Nigeria's yam yield has dropped to its lowest level in two decades, according to the United Nations, even though the area of land under cultivation is rapidly rising.

"For a large number of farmers, seed yam is a big problem," said Robert Aseidu, West Africa research director for the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), a nonprofit research organization based in Nigeria. "It's only now that we're seeing how big a problem this could become."

The trouble stems from the way yam is grown by Nigeria's small farmers. New tubers grow directly from planted pieces of old ones, rather than from seed. Traditionally, farmers will set aside the more measly yams from each harvest to use as seed yams for the next season, and take the bigger ones away to eat or sell. Having a big enough harvest to be able to keep your own seed yams is a mark of a farmer's competence; buying them at the market is considered bad luck.

At the same time, yams are clonal, meaning that each tuber is genetically identical to its "parent." So farmers are essentially planting the same yam over and over again, with none of the routine genetic mutation that typically occurs between generations to help ward off pests and diseases. And because farmers tend to set aside the worst yams as parents, they're unintentionally practicing a kind of anti-Darwinian "survival of the scrawniest."

"When you have this recycling over so many years, then they keep accumulating pests and diseases, and then productivity keeps reducing until you get to a stage where it's no [longer] economical to plant anything," says Beatrice Aighewi, a yam specialist at IITA.

That cycle is reaching a crisis point, forcing a reconsideration of the longstanding stigma against buying seed yam. Adaikwu opened her business a few years ago to take advantage of the emerging market. She sources good seed yams from around the country and reproduces them in her field. One of her first big hits was a high-yielding, disease-resistant variety that earned the nickname "Mecca Approaches," because of a reputation that it could help farmers earn enough money to make the pilgrimage to Islam's most holy site.

Nigeria leads the world in both the production and consumption of yams. Yet it still struggles to meet its own demand, hampered by systemic issues throughout the supply chain such as the ones listed above. It is therefore profoundly telling that one can build the country's largest and most valuable food company without ever touching a product so central to the Nigerian experience.

Nowhere in BUA Foods Plc’s 2024 annual report is there a single mention of yams. The document similarly omits any dedicated research and development function or a clear R&D line item in its financial statements - a vague reference to “research funding” on page 79, tied to education, is the most you’ll find. Under “Product Innovation,” the company describes adding premium pasta and semolina as its method of “staying ahead of industry trends.” Let me be clear: this is not merely Nigeria’s largest food company. It is the most valuable company in the country, full stop.

Should a foreign innovator ever solve yam's production problems, the local "entrepreneur" would swiftly leverage government connections to seize the opportunity. This is the very model of innovation outsourced and rent-seeking domesticated. The business model is to use tariffs to inflate the price of imports, then price their own local product at the same level (or even above) to secure outsize profits. We've seen this before. When China developed waste-heat innovation for cement, the benefits weren't passed to Nigerians; they were captured by middlemen who charged rent for the privilege of access. The F.O.O.D framework can be observed in the country’s palm oil industry as the players make vast profits while you can still see palm oil production in Nigeria that looks like something from the nineteenth century.

It is for this reason that someone can get very rich in Nigeria while the country remains very poor - a malnourished economy on a diet of outsize profits. The incentive structure within Nigeria's nominal market economy is fundamentally broken. The psychological toll is immense, as a generation learns the demonstrated truth that improving lives is optional for acquiring wealth - the F.O.O.D. framework is all that is required. Even investors and fund managers, resigned to a lack of better options, validate this model in their pursuit of returns.

When this is an economy's only sustenance, the nation is guaranteed to starve.

Clearly, Feyi’s F.O.OD analysis shows how Nigeria has become a system where wealth is built not by creating value, but by exploiting regulatory shields.

…and until innovation and problem-solving become as rewarding as rent-seeking, Nigeria’s economy will keep enriching a few at the expense of the many.

Imagine,

Right on the money as usual. I hope this is read widely as one thing that worries me is that even among supposedly well educated Nigerians there is a refusal to open their eyes and actually take in what is happening to their country.