The Food Problem

Some of the things I have been reading on food and development

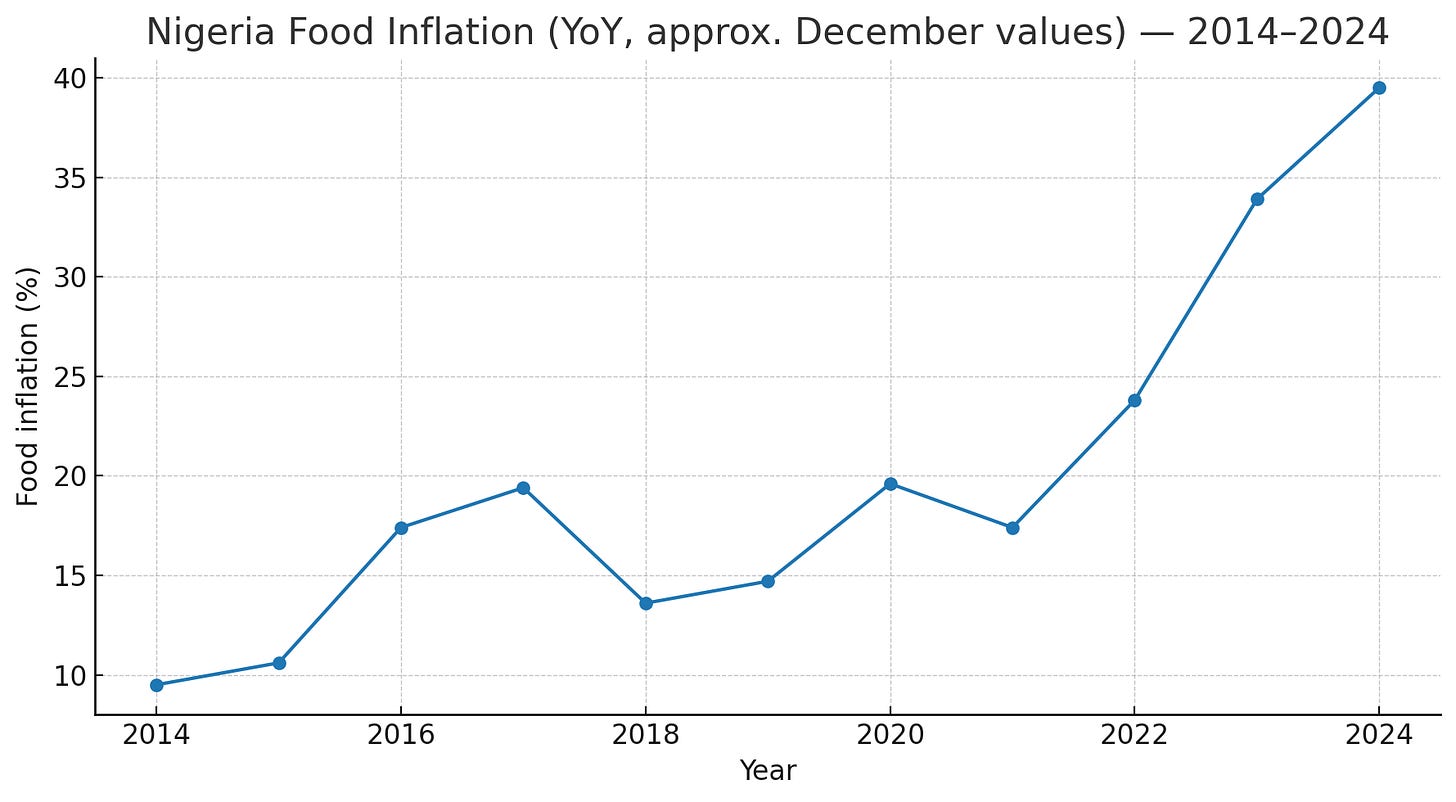

There is a popular Yoruba proverb that loosely translates to "a hungry stomach has no room for any other discourse." I was reminded of it during the recent debate on social media about the stability of Nigeria's economy and what that means. The harsh reality of life in Nigeria today is that only those who can afford food have the luxury of technically distinguishing between economic stability and economic hardship. People are hungry, and only those who are not hungry can afford the luxury belief that importing food is the problem.

I have written extensively in these pages about hunger and Nigeria's misguided agricultural policy. New readers can always revisit those arguments through the links, so I will not repeat them here. Instead, I want to share some of the things I have been reading lately.

Food Prices Are Political

A recent paper titled The Political Economy of Maize in East Africa: How Cheap Food Turned Expensive by Ewout Frankema, Michiel de Haas, Tanik Joshipura and Thomas Westland offers a detailed, historically grounded explanation of why maize, a critical staple food in East Africa, became increasingly expensive over the 20th century. The authors argue that maize price inflation is best understood as a long-term outcome of political economy dynamics that evolved in the postcolonial era. They also challenged the dominant explanations that attribute high food prices either to urban bias (a thesis popularised by development scholars Michael Lipton and Robert Bates, which holds that agricultural policy in Africa often favours urban consumers against rural farmers) or to external shocks such as global commodity cycles. However, they acknowledged the role of global and regional pressures.

Governments in developing and urbanising countries often face a difficult choice: support farmers by keeping crop prices high, or support urban consumers, especially workers, by keeping food prices low. This is known as the Food Price Policy Dilemma (FPPD). In practice, governments tend to pursue four broad approaches. Some attempt to raise agricultural productivity, which is the ideal solution, but also the hardest since it requires sustained investment in technology and extension services. Others try to reduce costs in the food supply chain through improvements in transportation and logistics, though this demands infrastructure capacity that many states struggle to build. A third path is to raise urban wages so that workers can cope with high food costs, while a fourth is to subsidise food consumption or production directly, which carries the familiar risks of inflation and mounting debt.

Frankema and his colleagues show that East African governments attempted all of these strategies at different points, but they either executed them poorly or ran up against the limits of weak state capacity and dependence on export crops.

The paper finds that maize prices in East Africa rose steadily from the 1940s, peaked in the 1980s, and never returned to early low levels. Crucially, this was not driven by global markets but by domestic political choices and institutional failures. Marketing boards, rather than improving efficiency, added layers of cost, corruption, and inefficiency. Governments feared that if they did not support maize farmers, those farmers would switch to more profitable export crops such as coffee, risking food shortages.

The core argument is that cheap food became expensive because governments clung to politically popular but economically inefficient policies. They underinvested in productivity and infrastructure, mismanaged state interventions such as agricultural marketing boards, and avoided difficult political trade-offs. The authors conclude that, contrary to narratives such as urban bias, East African governments in this period favoured producers’ interests, and the cost was borne by consumers and the wider economy.

The findings did not surprise me. They feel all too familiar. Still, it is an impressive piece of scholarship. What struck me most is how little African governments and elites have learned from history. Hunger and food scarcity persist because of policy inertia. Although the authors were careful not to generalise beyond their case studies, I am convinced that the same political economy pattern is visible in other major African economies. The persistence of impoverishing food policy continues to undermine economic development across the continent.

Food Price and "Divergence"

Staying with the theme of food and development, I was reminded of an old blog post by Thomas Westland, one of the authors of the maize paper. The vast income gap between countries in the global north and south over the past two centuries is popularly known as "The Great Divergence." But Westland drew attention to a smaller, less discussed pattern he called "little divergence."

Up until the 1970s, income levels in West Africa and Southeast Asia were relatively similar. After that, Southeast Asia surged ahead, while much of West Africa stagnated or grew more slowly. There is no single reason for this divergence, but Westland focused on wages, food prices, and industrial competitiveness.

In the early period, wages were high in both regions because land was abundant and labour scarce. But the emergence of Japan as a regional industrial powerhouse provided Southeast Asia with a catalyst for investment and competitiveness. West Africa lacked such a leader.

Westland argues that food prices are an underappreciated part of the divergence story. High food prices push nominal wages upward because workers need more money just to eat. High wages, in turn, make it harder for domestic industries to compete globally. This is known as the "unit labour cost problem." Colonial and postcolonial governments often feared unrest from food shortages or high prices, and so they tried to keep nominal wages artificially low. But this created a policy dilemma: how to keep real wages, meaning purchasing power, high enough to attract workers from farms into factories, without pushing nominal wages so high that industries lose competitiveness.

The issue of labour costs in Africa has long generated debate. Westland’s work strengthens the argument that food prices are central. He found that food was consistently more expensive in West African cities than in Southeast Asian ones, even in the early 20th century. Post-WWI food inflation hit West Africa especially hard, and while the gap narrowed during the Great Depression, West Africa remained relatively expensive.

This suggests that Africa’s high food prices are not a modern development but a deeply rooted historical pattern. If food has always been costly, then urban wages had to remain high, making low-wage industrial growth difficult. That challenge is compounded by limited access to foreign investment.

The Food Problem

Another work that illuminates the connection between food and development is The Food Problem and the Evolution of International Income Levels by Douglas Gollin, Stephen L. Parente, and Richard Rogerson. The authors take up a fundamental question: why did some countries begin sustained growth centuries earlier than others, and why do income differences between nations persist even when technology has spread widely? Their answer rests on what Theodore Schultz once called “the food problem.”

The idea is simple. Poor countries must devote most of their resources to simply feeding themselves. With the bulk of income and labour tied up in subsistence farming, little is left for industry, trade, or savings. Modern growth is delayed until food can be produced more efficiently, because importing it is rarely affordable. Until that basic need is met, economic transformation cannot begin.

What the authors of this paper show is that agricultural productivity largely determines the timing of growth. Where farming is too unproductive, economies remain stuck. Once food output rises above a threshold, however, the door opens for industrialisation and sustained increases in living standards. This helps explain why countries starting with low agricultural productivity often entered modern growth centuries later than Britain or Western Europe.

The consequences go far beyond the initial delay. Early differences in farming productivity continue to shape income levels long after agriculture has shrunk as a share of the economy. The timing of industrialisation, the speed of structural change, and the size of the gap between rich and poor countries can all be traced back to how quickly nations solved their food problem.

Another key lesson is that industrial progress on its own is not enough. Many countries have tried to modernise by focusing on factories, services, or institutional reforms, yet without improvements in agriculture, they remain constrained by subsistence. You cannot build a modern economy if much of the population still struggles to meet basic food needs.

The message of this work is simple. Solving the food problem is integral to economic development. It shows why some countries stagnated for so long and why catching up is such a slow process, even for latecomers that adopt better policies. Agriculture may be a shrinking share of national output, but its role in setting the conditions for development is decisive. The policy implication is clear - no country can modernise without first feeding its people. Global inequality has deep historical roots in differences in agricultural productivity, and solving the food problem remains the first barrier that must fall before others can follow.

Wizard Wanted

The Green Revolution remains one of the most striking examples of how science and policy can change the fate of entire societies. Beginning in the 1960s, new high-yielding varieties of wheat, rice, and maize spread rapidly across Asia and Latin America, supported by irrigation, fertilisers, and pesticides. Food production surged. What had once seemed like an inescapable scarcity trap of hunger suddenly gave way to rising harvests, lower prices, and greater stability.

In their paper Two Blades of Grass: The Impact of the Green Revolution, Douglas Gollin, Casper Worm Hansen, and Asger Wingender trace its broader consequences for the Global South. Their question was simple but far-reaching: how much did this agricultural transformation matter for economic development as a whole? The answer is that it mattered enormously. By their estimates, without the Green Revolution, income levels in developing countries would have been much lower, global GDP per capita in 2010 would have been about 17% smaller, and the poorest countries would still have been hundreds of dollars poorer per person in real terms. They calculate that a ten-year delay in spreading these new crop varieties would have cost the world an estimated eighty-three trillion dollars of lost output. The Green Revolution also slowed population growth and enabled structural transformation, as higher food output freed labour and resources for work outside farming.

The scale of this achievement cannot be understood without Norman Borlaug himself, the scientist at the centre of Charles C. Mann’s The Wizard and the Prophet. Borlaug is cast as the “wizard,” the figure who believed that human ingenuity and technology could always push back the boundaries of scarcity. His high-yielding wheat varieties saved millions from famine, and his philosophy was clear: feed people first, and deal with the side effects later. Opposite him stood William Vogt, the “prophet” of limits, who warned that humanity must reduce consumption and live within the planet’s carrying capacity. Mann presents their visions as two enduring archetypes - one that trusts in innovation, and one that counsels restraint.

Africa today stands at a point where the wizard’s intervention is desperately needed. The continent is still held back by the food problem. Hunger and high food prices trap millions in subsistence and delay the process of transformation. This is not a call to ignore relevant warnings and concerns about our environment and climate. For Africa, wizards are wanted. Scientists, policymakers, and innovators willing to set clear policies, apply scientific research, and invest in the seeds, soils, and food systems that can deliver Africa's Green Revolution. The lessons of Borlaug’s life, and the overwhelming evidence from Asia and Latin America, show that this is not just some fancy aspiration but a practical necessity. The choice is not whether Africa should have a Green Revolution. The choice is whether it will have one soon enough to unlock its future.

The task at hand in Nigeria is very clear. We can no longer afford to be in a perpetual economic stabilisation trap without transformation. Everything I know from the works of serious scholars and have written about has shown that there will be no transformation if the food problem persists. We cannot build human capital while poverty and hunger corrode the body and the mind. We cannot put our best brains to work when they spend all their earnings on food.

The tragedy of hunger is not only material. As Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir argue in Scarcity,1 the condition of having too little taxes the mind. Scarcity narrows attention, drains cognitive bandwidth, and traps people in short-term cycles. Hunger does not just empty the stomach; it crowds out the capacity for planning, learning, and creativity. The Yoruba proverb captures this reality with painful precision: a hungry stomach has no room for any other discourse. Yet in Nigeria, the very act of worrying about food is often mocked, as if hunger were a sign of weakness rather than the most basic human constraint. To ignore the food problem is to misunderstand scarcity itself. Agricultural productivity, extension services, and technology must therefore become matters of policy action, not empty rhetoric. Food policy must escape the eternally corrupt and terminally dangerous narrative of self-sufficiency. What we need is food abundance. Scarcity must never be an option.

Links to previous posts on the subject.

Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much - Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir

It's such a moving piece. And I can't help but link this persistent food problems to Africa's low IQ because nutrition matters for a highly functioning brain, even across generations. But here we are where most Africans are barely able to afford food from generation to generation.

So we need abundant nutritious food at affordable prices, consistently, for like 100 years. That has to be the goal. There's no way we'll solve this problem of agricultural productivity and not have transformed our economies.

"Food policy must escape the eternally corrupt and terminally dangerous narrative of self-sufficiency. What we need is food abundance. Scarcity must never be an option"

I couldn't agree more with this part of this piece.

Thank you, Mr. Tobi.