Revolutionary Cosplay

How Intelligence spared Nigeria and West Africa the worst of the Cold War

The Cold War's genesis lies not simply in post-1945 tensions, but rather crystallised when Soviet espionage successfully stole - through its spies - America's most closely guarded technological secret: the atomic bomb's complete design and technical details. The Soviets' 1949 nuclear test—an exact replica of the device deployed against Japan four years earlier—irrevocably transformed the post-war global order. As this conflict unfolded predominantly through espionage, counter-intelligence, deception, code-breaking and misinformation, it sowed profound paranoia that transcended the borders of its principal antagonists: the United States, Britain and the Soviet Union.

For the longest time, the shadowy world of Cold War espionage remained hidden from public scrutiny. In Britain, the Official Secrets Act was so stringent that merely acknowledging that MI5 had a canteen could constitute a criminal offence. Parliamentary discourse demanded linguistic contortions to avoid even acknowledging MI5's existence, let alone discussing its operations or methodology. Indeed, it wasn't until 1992—after the Cold War's effective conclusion—that an MI5 Director General (Stella Rimington) was ever publicly identified1.

Across the Atlantic, President Truman's National Security Act of 1947 established the institutional framework that would define American intelligence operations throughout the conflict. This legislation created the CIA and National Security Council while consolidating the previously separate War and Navy departments into a unified Department of Defence. It further established the Joint Chiefs of Staff, bringing together the three service chiefs under a single chief of staff to advise the President directly. This security architecture—constructed specifically to counter the Soviet threat—remains instantly recognisable to even casual observers of the subject today.

In the Soviet Union, intelligence operations evolved through a succession of organisations—the KGB having previously existed as the Cheka, OGPU, and NKVD, and later fragmenting into the FSB and SVR. Originally established as an instrument of domestic repression and the self-proclaimed "sword and shield" of the Communist Party, its international espionage arm, the First Chief Directorate (FCD), emerged as an offshoot of its domestic secret police unit. At its peak, the KGB commanded a staggering workforce approaching one million personnel, with approximately 20,000 dedicated to the FCD's foreign intelligence activities. This formidable apparatus constituted a substantial component of the Soviet state infrastructure, and as previously noted, its influence extended considerably beyond Soviet territorial boundaries.

He is a Communist

In this atmosphere of suspicion, being branded a Communist in Western nations (or conversely, a capitalist in Eastern bloc countries) could effectively constitute a death sentence. Yet such paranoia was not entirely unfounded—genuine threats did exist, and perhaps no incident better exemplifies how dangerously close ideological mistrust brought the world to catastrophe than the Able Archer 83 NATO military exercise. This simulation so convincingly mimicked preparations for a nuclear strike that it triggered genuine alarm within Soviet intelligence, bringing the superpowers perilously close to mutual destruction fuelled by entrenched suspicion and fear.

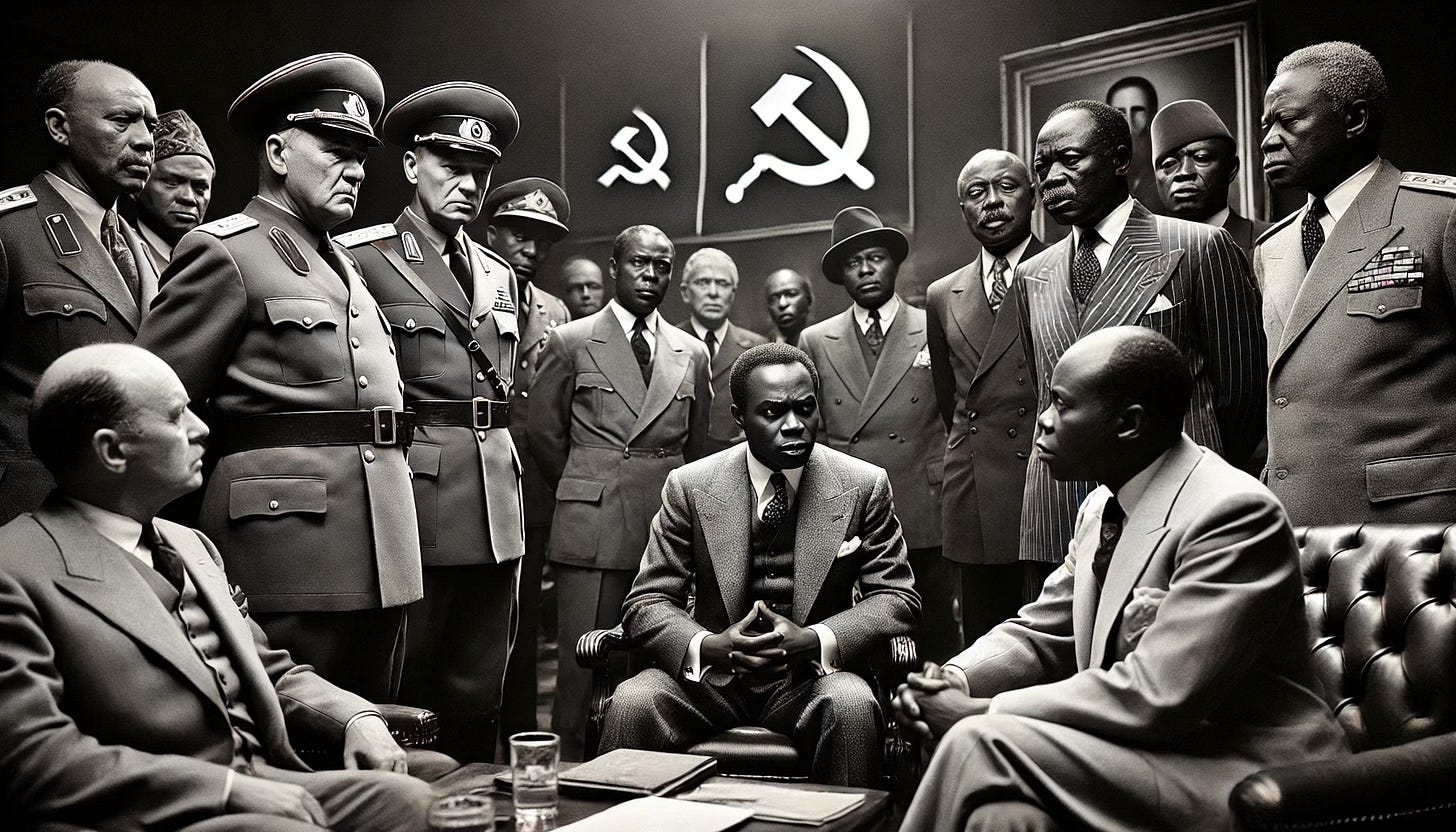

Patrice Lumumba stands as perhaps the most prominent African casualty of Cold War geopolitical machinations. As meticulously chronicled in Stuart Reid's illuminating book about his life and death (my review below), Lumumba's greatest misfortune lay in his ordinariness—an unremarkable individual thrust suddenly into leadership of an vast and complex country. His purported Marxist leanings were superficial at best, and he would have posed a negligible threat to interests beyond Congolese borders. Yet the erroneous Communist label affixed to him effectively initiated the countdown to his demise, transforming a domestic political figure into an international target within the broader East-West conflict.

In that context, it is actually remarkable how Nigeria—the most populous British colony outside of India—and the broader West African region largely evaded the Cold War's destructive impact. Initial signs were certainly troubling. In February 1948, violent protests erupted in the then Gold Coast (today’s Ghana), with demonstrators demanding immediate independence (the demonstrations overlapped with another by Veterans who had fought for Britain in the war, three of whom were killed2). The confrontations resulted in 29 fatalities and over 200 injuries. While protests were not unprecedented within the British Empire and considerably larger demonstrations had occurred across Asia, they represented a novel and alarming development in West Africa. More worrying for British authorities was the timing, coinciding with the Malayan Emergency—an undisputedly Communist-fuelled insurgency—making it a reasonable consideration whether Communist influence had penetrated West Africa as well.

In August 1948, the Colonial Secretary, Arthur Creech Jones, wrote the following circular to all governors and police commissioners across the Empire3:

It is in my view essential that every possible means should be taken to prevent similar happenings in other Colonial territories, and there is much evidence that the sources which have inspired the outbreak in Malaya (and have some indirect responsibility for those in the Gold Coast) are on the lookout for similar opportunities elsewhere.

At this point, the concept of independence for Britain's African colonies was considered a distant prospect. A Colonial Office report published in 1950 explicitly stated that Nigeria's independence from Britain would require “decades”. Earlier, in 1947, the influential Caine-Cohen Report (co-authored by an exceptionally capable Colonial Office civil servant Andrew Cohen) had recommended gradual progression towards self-government for African colonies. However, it simultaneously cautioned that even in the Gold Coast—then the most politically advanced colony—independence would likely not materialise for “at least a generation”. The rationale behind this measured approach was uncomplicated: British authorities feared that a precipitous withdrawal from African territories would create a vacuum readily exploited by Soviet influence, with Communism finding fertile ground amongst numerous pro-independence leaders of the era.

Socialites, not Socialists

And yet, within a decade, the “winds of change” had swept across the continent and independence proliferated throughout Africa. Ghana achieved sovereignty in 1957, with Nigeria following three years later in 1960. What precisely dispelled British and Western apprehensions, allowing independence to proceed without the feared Communist encroachment? The straightforward answer is that genuine Communists were essentially non-existent in Nigeria and West Africa. The more nuanced explanation, however, lies in how Britain developed its conviction that Communism posed no significant threat in West Africa: through sophisticated intelligence operations.

Kwame Nkrumah, whilst the most prominent African leader under MI5 scrutiny, was not primarily the subject of their surveillance efforts. Rather, he had been flagged to British intelligence by the FBI, who had monitored him during his American studies due to his associations with various Marxist groups (working definition: a Marxist is someone who reads Das Kapital and critiques capitalism in theory, while a Communist is someone determined to overthrow it in practice). The real focus of MI5's surveillance was the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), perceived as a genuine threat to national security, with all members and communications placed under comprehensive watch. Declassified internal MI5 reports consistently emphasised that pro-independence movements represented legitimate political aspirations; they were monitored solely because of potential Communist connections. Consequently, any individual or organisation exchanging correspondence with the CPGB found their mail intercepted and activities meticulously tracked by British intelligence services.

Initial evidence suggested Nkrumah was indeed a dangerous Communist, with British newspapers publishing alarming reports of the Ghanaian leader casting a “Red Shadow over the Gold Coast”. Given the escalating Cold War tensions of the period, it is not hyperbolic to suggest Nkrumah's life hung precariously in the balance. Yet paradoxically, MI5's extensive surveillance—including the interception of his personal correspondence—produced a reassuring effect. When the Colonial Office commissioned a comprehensive assessment of Nkrumah's political ideology in 1951, MI5's resulting report offered a dismissively condescending conclusion:

It would be unwise to base any too definite a conclusion about N’KRUMAH’s evolution as a nationalist politician upon his early career. He has certainly received a thorough grounding in Marxism and has received moral support from the British Communist Party during its rise to power. He is politically immature, however, and there are indications of an individualism in him which may ultimately override his communist training… Source TABLE [the bugs in the CPGB headquarters] indicates that the British Communist Party are no longer confident that their protege will remain faithful to them.

I believe it was Rotimi Amaechi, the former Nigerian governor and minister, who astutely observed that Nigerian politicians are "socialites not socialists"—a penetrating insight into the fundamental limitation of ideological influence upon them. In his view, socialism, and particularly the self-denial demanded by communism, represented an insurmountable psychological barrier for the Nigerian political class. This assessment was corroborated at the highest levels of British intelligence when, in 1953, MI5 Deputy Director-General Roger Hollis submitted a comprehensive evaluation of Communist activity throughout Britain's African colonies. His report triumphantly concluded, much to Whitehall's relief, that not a single organised Communist party existed in any British-controlled African territory. These assessments later fed through to Harold Macmillan who was thus convinced that the “winds of change” blowing through the continent would not be as damaging as initially feared.

Early intelligence reports similarly scrutinised Thomas Sankara, with American authorities characterising his politics in diplomatic cables as "radical populism...a better description of the nature of his regime than a variety of Marxism or socialism". Sankara himself acknowledged ideological pragmatism with his observation that: "the people do not feed themselves with ideology. What good is there in proclaiming oneself communist or Marxist if the people die of hunger?" While he undeniably engaged with leftist thought—cultivating a friendship with Fidel Castro, frequently criticising his international donors, and admitting to reading Lenin "whether in good or bad mood"—his ideological positions remained notably fluid. More significantly, the Burkinabé population ultimately grew weary of his relentless revolutionary fervour. As one teacher said of him4:

Sankara was a full-time revolutionary and he pushed the people too hard. And so the people were tired of the revolution. It was like being in Albania or something, becoming communists

He is not a Communist

In Nigeria, there were no Communists to be found either. While MI5 and the Nigerian Special Branch were severely under-resourced in Nigeria with only 5 Brits and 50 Nigerians to cover the entire country in 1953, they were still able to produce valuable information for the colonial administration. Nnamdi Azikiwe being the leading nationalist politician at the time, had detailed intelligence produced about him. They wrote:

He is not a communist, but he is very ready to accept the support of communists whenever he considers it likely to further his own interests.

The report also, rather comically, described Azikiwe as "powerful as an ox"—a nod to his distinguished past as an internationally acclaimed athlete. Their surveillance operation deployed plainclothes officers to political gatherings and confiscated substantial documentation during raids on “Zikists”. By 1956, they had established a top secret "Radio Monitoring Service" within Special Branch operations, a considerable investment requiring £800 in equipment costs and annual running expenses of £1,000, representing very large sums at the time. This surveillance apparatus maintained continuous round-the-clock monitoring of unauthorised radio transmissions from Nigeria to neighbouring West African territories. Whilst designed to detect Communist infiltration (and indeed intercepting some such communications), the service proved most valuable in identifying broadcasts critical of Azikiwe himself. Special Branch shrewdly exploited this intelligence to cultivate Azikiwe's confidence by sharing these findings, which he found "extremely informative", a masterful counterintelligence manoeuvre that effectively neutralised a potential ideological adversary.

The View from Moscow

All of this apparent absence of Communist activity represents, of course, merely the Western perspective. Evidence confirms that the Soviet Union made determined efforts to establish Communism throughout Nigeria and Africa where opportunities presented themselves. But how did Moscow evaluate the effectiveness of its own initiatives?

For centuries, Africa had occupied a problematic and enigmatic position in the Russian mind. The celebrated Russian children's poet, Kornei Chukovsky, captured this in his 1961 poem Doktor Aibolit:

Africa is no place for walks, kids

There are sharks in Africa

There are gorillas in Africa

There are big and mean crocodiles in Africa

Who will bite you

Who will beat you

Who will make you miserable

Africa is no place for walks, kids

This ingrained perspective meant the Soviets dedicated minimal resources to Africa through the Comintern (Communist International), likely recognising the improbability of meaningful returns on such investments. They determined their efforts were better directed towards Black Americans and Caribbean intellectuals (such as George Padmore, Nkrumah's friend and confidant). By 1934, as Stalin consolidated power and sought alliances with Great Britain and France against Nazi Germany, all African research initiatives were abruptly terminated, with virtually every “Soviet Africanist” of the period dispatched to the gulags. Stalin concluded that workers wielded negligible influence across Africa, leaving collaboration with the “national bourgeoisie” as the only viable option, a prospect fundamentally antithetical to communist principles. Comintern operatives received explicit warnings that any such collaboration would result in summary execution without possibility of appeal. Stalin and his ideological compatriots ultimately dismissed Africa as "the last spot on earth where any revolutionary drama could happen"5.

Until the late 1950s, the Soviet Union suffered from a remarkable dearth of academically trained Africa specialists. Consequently, MI5's inability to detect communist activity across Africa is hardly surprising, given that the Soviets themselves possessed virtually no substantive working knowledge of the continent during the crucial pre-independence period, a direct result of their ideological refusal to engage with nationalist “elites”. Nikita Khrushchev's ascension following Stalin's death in 1953 modestly recalibrated this approach, but the watershed moment arrived with the outbreak of the Nigerian Civil War in 1967. Moscow identified a strategic opportunity to compensate for decades of neglect by supplying the Nigerian government with weaponry that Britain and America had declined to provide. This pragmatic intervention effectively extinguished any remaining possibility that Nigeria might pursue a “noncapitalist development” trajectory, signalling the Soviets' complete abandonment of ideological purity in favour of realpolitik.

The Soviets' frustrations, viewed through the dispassionate lens of historical hindsight, occasionally border on the comical. The Russian academic L. Pribytkovsky lamented that the Nigerian populace was "apathetic, without a single Communist in its ranks", a damning assessment of revolutionary potential. A handful of Nigerian ideological stalwarts, notably Tunji Otegbeye—who established the Socialist Workers and Farmers Party of Nigeria (SWAFP) in 1963 and received Moscow's official recognition for his endeavours—made valiant attempts to spark revolutionary sentiment. Yet even the Lagos Daily Telegraph offered this withering assessment in 1964:

We warn the government to ban the Communist Party of Nigeria because the communist ideology is strange to us. It is opposed to our customs and social traditions and can do incalculable harm to our country

Otegbeye and his party received substantial Soviet financing, possibly reflecting Moscow's misguided conviction that they had discovered their political proxy for Nigerian dominance. The Soviets dispatched a high-ranking official delegation to attend the party's inaugural congress in Lagos in 1965, with Moscow Radio enthusiastically reporting that the congress had articulated a "clear-cut Marxist-Leninist political platform". Russian sources consistently inflated the party's membership figures to as many as 22,000 adherents, whilst American intelligence estimates suggested a mere 1,000. The organisation swiftly became embroiled in corruption and nepotism allegations, with accusations that Soviet funds were being misappropriated for personal enrichment. The respected Marxist intellectual, Eskor Toyo, denounced the SWAFP leadership for exhibiting "bourgeois irresponsible non-accountability and bourgeois ambition". Soviet educational scholarships reportedly benefited predominantly friends and relatives of SWAFP officials, who allegedly received complimentary gifts ranging from sewing machines to bicycles and enjoyed fully-funded international travel, all on the Soviet dime. Perhaps most hypocritically, the SWAFP established a property acquisition committee despite Otegbeye's previous condemnation of real estate investment as fundamentally "unsocialistic".

Where Britain harboured anxieties concerning Azikiwe and Nkrumah's Marxist leanings, Soviet assessments proved decidedly unimpressed. At a 1949 commemoration of Stalin's 70th birthday in Russia, a Soviet academic presented research characterising Azikiwe's Nigerian independence programme as "the ideology and policy of petty bourgeois national reformism", terminology unquestionably intended as criticism rather than commendation. The scholar further disparaged Azikiwe's perspectives as a "colonial edition of the reactionary American philosophy of pragmatism". Five years later, in 1954, a Russian ethnographic compendium of African societies entitled Narody Afriki offered this assessment of Azikiwe:

The political views of Azikiwe and his political line vividly reflect the inconsistency of the national bourgeoise. He fights for the self government of Nigeria, but this formula in itself is extremely vague and allows many different interpretations. The point of view of Azikiwe in relation to England has changed my times.

It is difficult to suppress laughter at these assessments, though they largely stemmed from the profound Soviet conviction that Nigeria's elite were inherently unreliable revolutionary vanguards. While this analysis contained elements of truth, it equally reflected Moscow's inflexible dogmatism; their categorical refusal to consider any movement not explicitly worker-led in a nation with a negligible industrial proletariat (both historically and contemporarily). The Soviets similarly dismissed the Action Group as a counterfeit political entity controlled by "feudal marionette princes of Yorubaland", whilst the Northern People's Congress received equally contemptuous characterisation as a "reactionary organisation", demonstrating their fundamental inability to engage meaningfully with Nigeria's complex socio-political landscape.

While relations between Nigeria and the Soviet Union markedly improved following the Nigerian Civil War—after Soviet ideological rigidity had yielded to pragmatism, as previously noted—the definitive blow to this partnership came with the Ajaokuta Steel Complex debacle. Nigeria had enthusiastically embraced Soviet assistance, convinced that Western powers deliberately sought to prevent Nigerian steelmaking capability and consequent industrialisation. The Nigerian authorities would subsequently be profoundly disillusioned by Soviet technical incompetence in the (non)delivery of this industrial facility, which remains perhaps the most lamentable example of governmental profligacy in Nigeria's history (for more on this, check out this thread I wrote on twitter 7 years ago).

The past is not the future

Perhaps there is contemporary relevance in this historical analysis. While conventional wisdom places the Cold War's inception after 1945, its true origins lie considerably earlier in the immediate aftermath of Russia's 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, which prompted Western interventionist efforts. Similarly, we may already be immersed in a new Cold War between Western powers and China, with worryingly familiar patterns emerging through current industrial-scale espionage operations. Though ideological underpinnings are notably absent from today's confrontation—China having embraced thoroughly capitalist economic practices—the stakes remain equally significant in this contest for global economic dominance.

Africa's greatest Cold War fortune was that its nationalist leaders wore Marxism as lightly as fashionable attire, a kind of revolutionary cosplay that both Soviet and Western intelligence quickly recognised for what it was. The continent's relative escape from becoming another bloody theatre of superpower proxy conflicts stemmed not from diplomatic brilliance, but from thorough espionage that calmed any fears about African "communism." Today, as we witness the unmistakable contours of a new Cold War emerging between China and the West, this time stripped of ideological pretence and focused purely on economic dominance, can it be taken for granted that Africa will be so lucky again?

History offers a sobering lesson: paranoia may have spared Africa once, but vigilance, not complacency, must be the watchword for any conflicts to come.

All our posts on 1914 Reader are free to read. But you may consider taking out a subscription to support our work - LINK

Spies: The Epic Intelligence War Between East and West (Calder Walton)

Anansi’s Gold: The Man Who Swindled The World (Yepoka Yeebo)

Empire of Secrets: British Intelligence, the Cold War and the Twilight of Empire (Calder Walton)

No Easy Row for a Russian Hoe: Ideology and Pragmatism in Nigerian-Soviet Relations, 1960 - 1991 (Maxim Matusevich)

lnsightful and engaging. We are truly socialites, never socialists.

Recently, a friend introduced me to his former schoolmate, who proudly called himself a Marxist. Having visited Havana a few times, he never missed a chance to criticize the bourgeois lifestyle.

Fast forward to last month at another friend’s party—he pulled up in a brand-new Toyota Venza. I jokingly remarked that he had fully embraced the bourgeois life. He just laughed it off.

On a lighter mood, we should expect no revolution from you soon, right?

😂

Insightful. Would appreciate a spotlight article on Tunji Otegbeye & the activities of the Communist Party of Nigeria. Thank you.