The Motivational Economy

Beliefs, expectations, and economic policy

I had silently vowed that I would not spill any more ink on these pages about Nigeria's immediate past president, Muhammadu Buhari, who died in July. However, to paraphrase Michael Corleone, just when I thought I was out, he pulled me back in. I made this vow not because I do not have things to say about him. But firstly, because it is impossible to do better than Feyi's obituary of him, which fully captured the man, both in essence and deed. Secondly, and perhaps paradoxically for someone who is one of the most consequential leaders Nigeria has ever had, Buhari deserves as much deliberate thought and attention as he gave to governing the country, which is little to none.

Feyi and I recently had a brief exchange on Substack Notes about the link between what people believe and economic outcomes. As can be seen in the exchange, my quibble was not with the influence of beliefs on economic outcomes; rather, it was with the essay Feyi linked to in his note, which is the familiar conclusion that the majority of Nigerians actually agree with the economic policies that continuously fail them. I will quote the opening bit of the piece for context.

The recent passing of former president Muhammadu Buhari has, predictably, unleashed a torrent of commentary on his legacy. My two favorites are the ones written by Tolu Grey and Feyi Fawehinmi. While debates rage about his character and political controversies, it is his economic philosophy, ‘Buharinomics’, that invites the most passionate condemnation. Almost everyone agrees: his administration impoverished Nigerians and wrecked the economy. This verdict, while correct in its assessment of the outcomes, is built on a foundation of profound intellectual dishonesty. The truth is that while Nigerians despised the consequences of Buharinomics, they wholeheartedly embraced its principles.

The author then went on to detail some examples of historical policy failures in industries such as textile, automobile, and cement, which showed the same economic illiteracy and misaligned incentives in policymaking that characterised "Buharinomics". The crux of the argument is that these policies persist because, despite repeated failures, they reflect the preferences of Nigerians.

Do Nigerians Endorse Bad Policies?

I disagree with the sweeping conclusion that the persistence of these policies means Nigerians endorse them. First, it is an empirical claim made without evidence. To my knowledge, there has never been any systematic survey of the economic policy preferences of ordinary Nigerians. Second, many of these policies reflect elite preferences rather than popular will. In my own experience, market women often explain comparative advantage and economies of scale with a better intuitive understanding of those concepts than civil servants and many white-collar types, who tend to dominate informal debates on social media — where most economic discussions now happen, unfortunately. Endorsements of poor policies also pass without serious pushback in the media beyond the perfunctory condemnation of corruption, because the country’s education system and scholarship have collapsed. There are no expert communities with a clear pipeline to policy advisory. In the absence of this, politicians often fall back on private sector professionals, who often have mixed incentives and lack the development policy knowledge and experience needed for good policymaking.

However, the real question is whose preferences shape policy. The work of political scientist Martin Gilens is one of my go-to sources on this subject. His research shows that policy tracks the preferences of the affluent when they diverge from everyone1 else. That result rests on thousands of issues and a clear link between measured preferences and later policy outcomes. Although Gilens' research is about the United States, I think it is reasonable to suggest that the lesson travels. Even if many Nigerians say they support protection or self-sufficiency, those views matter only when organised into interests that can act, fund, and punish. In Nigeria, that capacity sits with political and business elites, not with dispersed voters, consumers and informal workers (over 90% of the working population). Elite networks aggregate preferences, frame them as national goals, and carry them through the policy pipeline. Regular Nigerians do not have this leverage, so persistence of bad policies is better read as elite dominance and not popular consent.

Folk-Economic Beliefs

Even if Nigerians do hold these mistaken economic beliefs, that is neither unusual nor uniquely Nigerian. Citizens of far richer economies show the same patterns. Research by anthropologists Pascal Boyer and Michael Bang Petersen has shown that so-called folk-economic beliefs are not random errors but flow from our evolved psychology. People are quick to see trade as zero-sum, immigrants as free-riders, or profits as harmful because these intuitions once helped manage coalitions, fairness, and cheating in small groups. The real difference is not that Nigerians think this way but that Nigeria has lacked political entrepreneurs able to reframe these intuitions into useful, economically literate policy debates. Where other societies have institutions and leaders that can channel folk beliefs into workable reforms, Nigeria has left them to reinforce bad policies.

Beliefs Matter

My argument should not be read as saying that beliefs do not matter. Of course they do. Beliefs organise expectations and make action possible. Australian economist Cameron Murray, in a recent essay, went so far as to argue that beliefs are a fundamental factor of economic production:

To have a nation requires belief in imaginary lines on the earth. To have economic growth requires the belief that growth is possible. To have money, companies, and organisations requires beliefs in things that only exist in our collective minds. Trade and investment run on beliefs about the future and the reliability of trading partners.

The innovation incentive in markets also rests on beliefs.

New businesses start because someone believes something that others don’t. They believe, even if the odds are stacked against them, in what they are doing. Who starts a business they don’t believe in it?

Elon Musk believes we can start a human civilisation on Mars. I think he has now convinced many others. Is that collective belief powerful enough to make it a reality? I think it is quite clear that without his potentially irrational beliefs that space technology would not be where it is today.

He went on to speculate on some of the beliefs that he thinks matter for growth

Here is a package of beliefs that I suspect would be required for a prosperous and growing society. These are what I would be thinking about as the ruler of a new society emerging from a shipwreck or other fantasy scenario about rebuilding social order.

Economic growth is possible and desirable.

This is just stealing Harari’s main point. We also need to have some conception of what an economy is, what is growing, and why it is good.Governance organisations should foster growth.

If we believe growth is good, then we should believe that any governance structure that emerges has a crucial role in trying to achieve it.Property rights are important and tradeable.

The trading patterns that emerge when property rights exist help societies to reorganise for growth and I suspect that intellectual property also creates strong incentives for experimentation that is hard to create in other ways.Companies and productive organisations can and should exist and be allowed to form, reform, and dissolve.

I think that structures that help people form and reform organisations while limiting individual risk from bankruptcy helps enable risk-taking and experimentation necessary for growth.People and companies should experiment with new a better ways of doing things. This is a subpart of the idea that growth is possible and desirable. I think we also need to believe in the processes that achieve that.

Households should be based around families and be allowed to make decisions independently about their earning and spending decisions.

We need to believe in the distributed decisions of households to participate and production and consumption choices that are best for them.

I believe the scope of this argument is indefinitely expandable to all aspects of economic life. People need shared beliefs and expectations that markets work, trade makes everyone better off, and that the prosperity of others is not at their expense, before they can support policies that optimise for these outcomes. But if I want to put my money on the belief that I think matters the most - the absolute starting point - then it will be the one at the top of Murray's list. Believing that growth is both desirable and achievable is the foundation of any collective economic project. And this is what brings me to what Buhari did to Nigeria.

What Buhari Did

What Buhari did to Nigeria will take decades to undo. The damage was not only large. It was total. By some estimates, the country lost about half its GDP in real terms. Prices ran away from earnings, and life became unaffordable. Jobs disappeared. Poverty and misery multiplied at scale. But the worst thing he did was psychological. The best way to describe it is the triumph of despair. Buhari killed hope. He put the economy in a state where people stopped believing that their lives could be better. Investments stopped. Education crumbled, along with the hopes of building up human capital. Young people planned only to leave. The sanctity of life became meaningless. Kidnapping human beings for money rose to a level not seen since the Slave Trade.

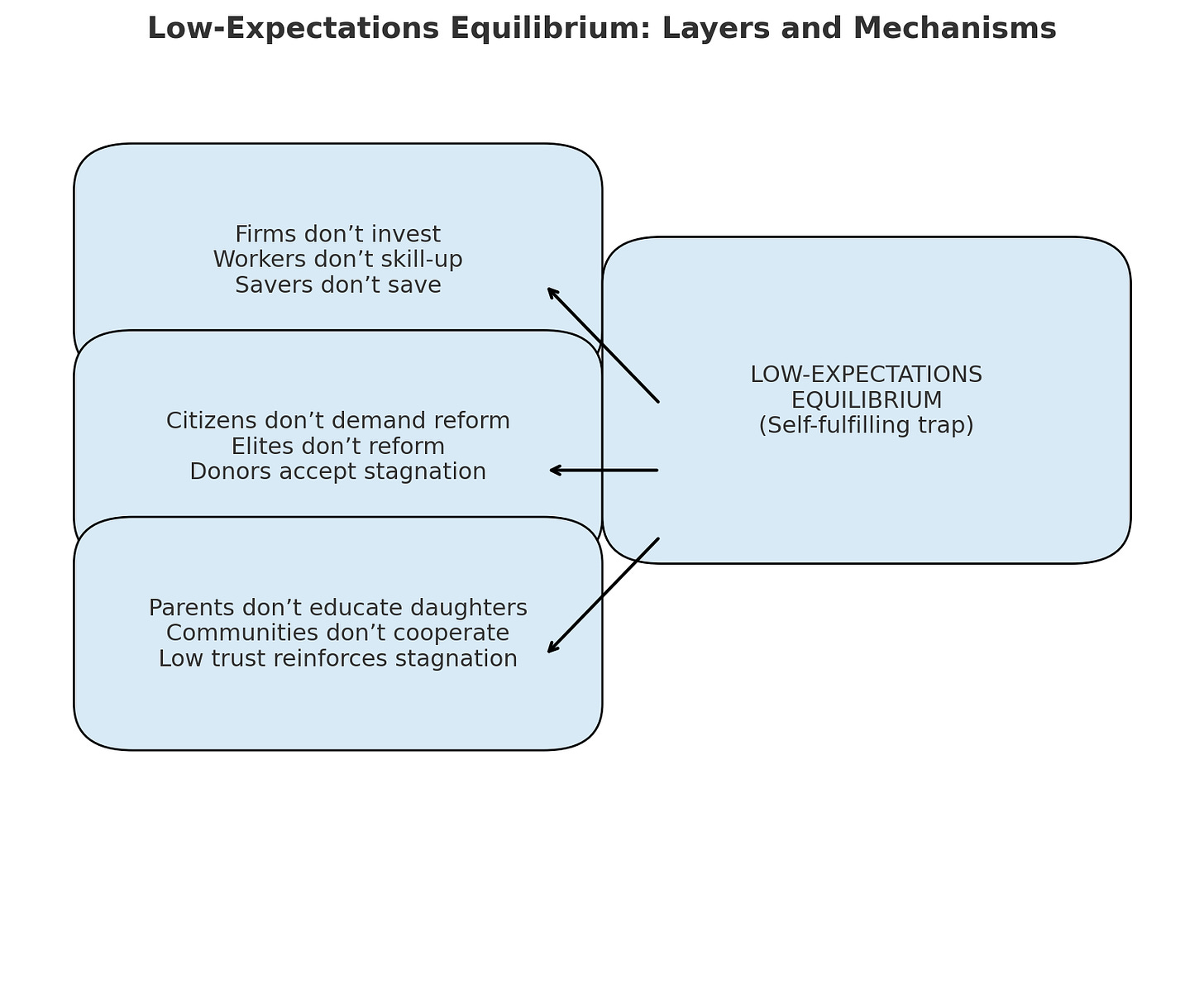

For a while, I struggled to find a framework that explained where Nigeria settled under Buhari. I found it in William Easterly’s idea of a low-expectations equilibrium.2 Under Buhari, Nigerians came to believe that growth would not happen. Because they believed this, they did not invest and did not demand reform. Economic risk-taking was constrained to isolated niches of state capture. This passivity and despair reinforced stagnation - and it is how a society gets trapped. Breaking out of it takes more than policies on paper. It takes credible commitments that change how people see the future, visible results that shift expectations, and a sustained record of delivery. Above all, people must come to believe that their efforts will give them a good shot at having a better life. That fortunes favour the brave, and not the connected. Rebuilding that belief will take more than jingles from the National Orientation Agency. It will require people to live, for years, with proof that their lives are getting better. That will be harder to build than any road, bridge, or power plant.

Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America - Martin Gilens

The Elusive Quest for Growth: Economists' Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics - William Easterly

We shouldn’t forget economic growth and economic development are incomparable. The former leans towards GDP - the latter - infrastructural development . A nation’s GDP , therefore, can be substantial in figures while more than half the population lives in poverty.

Economic policies which had worked in America or United Kingdom may never work in Nigeria because Nigeria eschews fundamental structures and laws.

A premier of a region in Nigeria advocated for a Social democratic system in 1950s , but his opponents , peers , even his family members laughed at him behind his back .

Now we are still debating about solutions to raise the standard of living for ordinary Nigerians.

A minimum wage at N300k a month is meaningless if our general hospitals are death traps, our public schools are pathetic, exorbitant food prices everywhere , public parks and public libraries nonexistent…In my opinion this is how you know a country is ready or has a vision to sustain development.

1. Allocation of budget for Education & health: 20% each.

2. Food must be subsidised.

3. Incentives to make our doctors remain in Nigeria .

4. Libraries in every LG.

5. Fund research institutions, etc.

Every thought articulated here - pure gold.