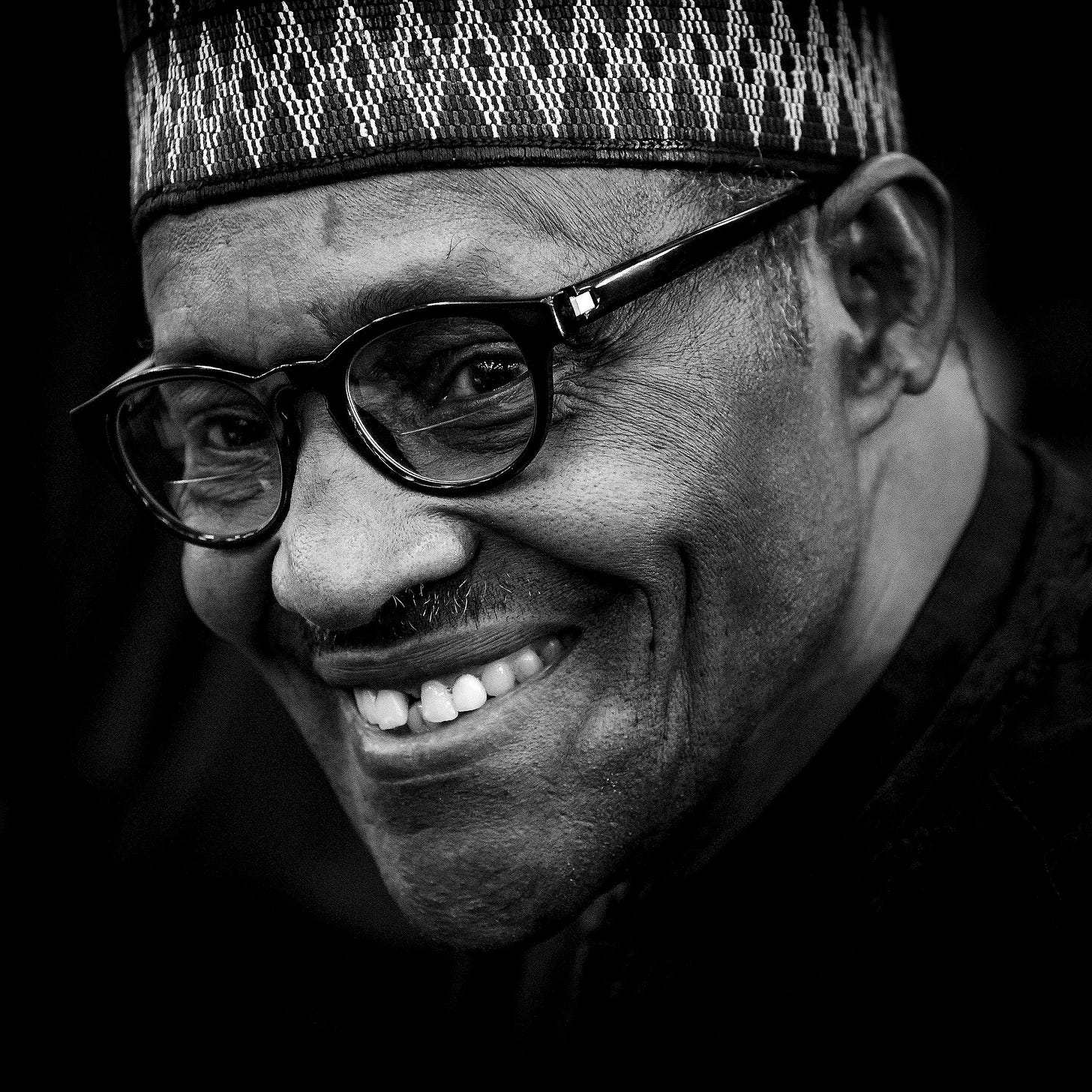

Sai Buhari

The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

There is a now forgotten story about Muhammadu Buhari from the late 90s that is useful to recount today. It is a tale of calculated silence, broken promises, and exquisite self-preservation, a portrait in miniature of the character who would one day lead Nigeria into economic catastrophe whilst maintaining his reputation for personal rectitude.

In 1993, as Nigeria's democratic hope lay strangled by military annulment, Buhari stood with Obasanjo and other former generals in the Association for Democracy and Good Governance in Nigeria (ADGN). Together they demanded an end to military rule, their united voices carrying the weight of former heads of state turned democrats. Here was Buhari the principled - aligned with justice, speaking truth to power.

But principles, it turned out, were merely the costume his personal vendettas wore. When Sani Abacha seized power later that year, Buhari accepted the chairmanship of the Petroleum Trust Fund, lending respectability to a regime many considered "satanic." The PTF - which remains, by some estimates, the largest intervention fund in Nigeria's history in dollar terms, with a ₦61 billion ($1.7 billion in today’s money) budget in 1995 alone - granted him control over billions whilst Obasanjo languished in prison. Throughout his one-time ally's three-year ordeal on trumped-up coup charges, Buhari uttered not a single word of protest. Instead, he diligently managed his unprecedented fiefdom, focusing on infrastructure projects with the quiet efficiency of a man who had found his calling in serving democracy's jailer.

This silence revealed not cowardice but calculation, rooted in his visceral hatred of Ibrahim Babangida - the man who had ousted him in 1985, whom he blamed for destroying his first marriage, and whom he would forever regard as a "life-time enemy." That Obasanjo would later emerge from prison to ally with Babangida only vindicated, in Buhari's mind, his refusal to lift a finger for his former comrade. His self-regard had so narrowed his vision that he could see only personal grievance where others saw injustice. When pressed in May 1998 about his future, Buhari declared on BBC Hausa Service that he would resign from the PTF by October. "I am not a politician," he insisted. "I have nothing to do with politics." It was an unequivocal promise to exit public life once the military transition ended - though like most of his promises, it would prove negotiable when self-interest beckoned.

When Abacha died unexpectedly and Nigeria's democratic transition accelerated, Buhari's promise evaporated like morning dew. Instead of resigning, he launched a furious lobbying campaign to preserve the PTF. He secured private audiences with the transitional head of state, Abdulsalami Abubakar. He dispatched emissaries to president-elect Obasanjo. He even backed an audacious scheme to embed the PTF into the new constitution as a "Nigerian Development Fund" - ensuring his continued relevance in the democratic dispensation he had once disavowed. Only when it became abundantly clear that Obasanjo would abolish the PTF did Buhari execute his masterstroke: he resigned precisely 48 hours before the new government’s inauguration. This perfectly timed exit allowed him to maintain his aura of incorruptibility whilst avoiding the ignominy of dismissal. No crime had been committed. No scandal attached to his name. He had simply recognised the changing winds and trimmed his sails accordingly.

This episode reveals something fundamental about Buhari that would echo through his presidency years later. Here was a man who never lifted a finger for anyone but himself - not for democracy when it mattered, not for a colleague unjustly imprisoned, not even for his own stated principles. His was an insularity so complete that it could accommodate serving a tyrant whilst maintaining personal honour, breaking promises whilst preserving reputation, abandoning allies whilst retaining admirers.

It was this same insularity - this inability to see beyond his own narrow conception of rectitude - that would later enable him to preside over Nigeria's economic devastation with a clear conscience. Adored by millions as a "good" man, Buhari would govern exactly as this forgotten story foretold: with rigid self-certainty, impervious to the suffering beyond his vision, incorruptible in person yet catastrophic in impact. The PTF saga was a prophecy written in the unmistakable hand of character.

Almost doesn’t count

In hindsight, Nigeria came tantalisingly close to avoiding the economic disaster Buhari would unleash upon it. Having already lost three presidential elections - in 2003, 2007, and 2011 - the country merely needed to resist him one more time and he would have been consigned to history, another ex-general whose moment had passed.

But here, once again, Buhari rose magnificently to the challenge of lifting a finger for himself. The man who had previously maintained a Covid-like social distance toward politicians he considered beneath him, suddenly discovered the virtues of proximity. He forged alliances with the very southwestern political machinery he had once regarded with undisguised contempt. Most remarkably, he allied with Bola Tinubu - the Lagos political godfather whose ideological flexibility and transactional approach to politics represented everything Buhari had claimed to despise.

This was the masterstroke that transformed his electoral fortunes. Where his previous campaigns had crashed against the rocks of regional arithmetic - his formidable northern support, 12 million votes strong on any given day, insufficient against a united opposition - the new coalition solved the mathematical problem that had thrice defeated him. The southwest's political machinery, with its vast networks and sophisticated vote-delivery systems, provided what his austere righteousness never could: a path to victory.

He made other adjustments too. He traded his austere simplicities for tailored suits, courting the urban professionals who had previously dismissed him. Young, sophisticated operatives helped repackage his inflexibility as principled leadership, his economic ignorance as incorruptibility. But these were merely cosmetic touches on a fundamentally political transformation. What sealed his victory was not his rebranding but his willingness, at last, to play the very game he had long professed to abhor.

And so, in 2015, on his fourth attempt, Buhari won. The man who had shown such remarkable energy only when his own interests were threatened had finally secured the ultimate prize.

Misery, unleashed

The arithmetic of misery that defined Buhari's tenure tells its own story. Here was a man who, having failed catastrophically with command economics in the 1980s, returned to power and promptly repeated every mistake with the zeal of someone who had learnt absolutely nothing. His rigidity wasn't merely an intellectual limitation but an active choice to inflict needless suffering on millions whilst maintaining the serene confidence of a man convinced of his own rectitude.

Under his watch, Nigeria's economy grew at an anaemic 1.4% annually whilst the population surged ahead at 2.6% - a mathematical guarantee that Nigerians would grow poorer with each passing year. And poorer they became: GDP per capita plummeted from $2,600 in 2015 to $1,600 by 2023 (World Bank), even as peer nations surged ahead. Two recessions punctuated his tenure, in 2016 and 2020 - though his finance minister memorably reassured suffering Nigerians that recession was merely "a word." Meanwhile, inflation, that most cruel tax on the poor, spiralled from single digits to 22% by his exit, whilst unemployment tripled to 33%, creating a lost generation of young Nigerians with credentials but no prospects.

But it was in his second term that Buhari's economic illiteracy reached its apotheosis. In August 2019, he ordered Nigeria's land borders sealed - a policy he had first attempted as military dictator in 1984. For sixteen months, Africa's largest economy shut itself off from its neighbours, ostensibly to combat rice and drug smuggling. The results were predictably catastrophic: food prices soared, inflation spiked, legitimate traders were ruined, and Nigeria's neighbours seethed at this violation of regional protocols. Yet Buhari persisted, convinced that what had failed in 1984 would somehow succeed in 2019. It was governance by nostalgia. As the misery deepened, the Nigerian vocabulary expanded to accommodate new gradations of suffering. Words like Japa (to emigrate), Sapa (crushing poverty), and Palliative (a bitter shorthand for state failure) entered everyday usage - a vocabulary of struggle proliferating in direct proportion to the economic wounds inflicted upon them.

The human cost of this rigidity defies easy quantification. By 2022, 133 million Nigerians - 63% of the population - lived in multidimensional poverty, suffering overlapping deprivations in nutrition, health, and basic living standards. Child stunting, that most damning indicator of a nation's failure to nurture its future, remained frozen at 32%, with rates reaching 60% in parts of the north. These weren't statistics but stolen futures of millions of children whose cognitive potential was permanently damaged by malnutrition whilst their president pursued his quixotic war against market forces.

Perhaps nothing captured Buhari's indifference to human development more starkly than his appointment of Adamu Adamu as education minister. Adamu, who had desperately wanted to be his chief of staff but lost out in a power struggle, accepted the education portfolio with all the enthusiasm of a vegetarian asked to judge a barbecue competition. For eight years - the entirety of Buhari's tenure - this disinterested placeholder presided over Nigeria's schools. No reforms emerged, no vision was articulated, no urgency animated the ministry tasked with preparing 10-13 million out-of-school children for the future. A school feeding programme, hastily conceived and bedevilled by corruption, stood as the sole monument to eight years of educational neglect. That Buhari left Adamu in post for his entire presidency revealed his fundamental contempt for education, the one ladder by which ordinary Nigerians might escape the poverty his policies had deepened.

By 2023, Buhari had transformed Nigeria's economy into a powder keg awaiting a spark. His stubborn refusal to remove or even adjust fuel subsidies - which consumed ₦10 trillion during his tenure - created a fiscal time bomb that would require deft handling and genuine concern for ordinary Nigerians to defuse. His monetary madness, channelled through a compliant Central Bank that printed ₦24 trillion ($53 billion) to fund government spending, guaranteed that inflation would ravage Nigerian households long after his departure. The naira's 70% depreciation under his watch was merely the appetiser for the currency crisis he bequeathed. Even his final act - a chaotic currency redesign that withdrew 85% of cash, on the eve of national elections, without adequate replacement - seemed designed to inflict maximum pain for minimal gain, triggering riots as Nigerians couldn't access their own money. These stored dysfunctions would demand careful, compassionate leadership to unwind - though whether his successor possessed such qualities was another matter entirely.

This economic vandalism wasn't accidental but stemmed from Buhari's fundamental approach to governance: supreme indifference punctuated by sporadic, destructive intervention. He offered no coherent vision, no coordinating philosophy, no intellectual framework within which his ministers might operate. Instead, they wandered in conflicting directions, engaging in open turf wars whilst their president maintained his characteristic aloofness. The finance minister preached fiscal discipline whilst the biddable Central Bank governor - also left in place for the entirety of Buhari’s tenure - printed money. The trade minister spoke of opening markets whilst the president closed borders. The agriculture minister promised food security whilst policies guaranteed hunger. It was governance by discord, held together only by Buhari's monumental incuriosity about outcomes.

If economics revealed Buhari's intellectual rigidity, security - his supposed forte as a decorated general - exposed something worse: the hollow theatre of strongman politics. In 2016, barely a year into his presidency, Buhari donned military camouflage and flew to Zamfara to personally launch Operation Harbin Kunama (“scorpion sting”) against bandits terrorising the state. The imagery was carefully crafted: the old soldier returning to the field, bringing order through force. Yet by 2023, that same Zamfara had descended so far into anarchy that the government was conducting negotiations with "top terrorists" - a capitulation so complete that one bandit kingpin, aggrieved at being excluded from the talks, kidnapped university students in protest at his snub. The grotesque inversion from crushing bandits to appeasing them captured the trajectory of Buhari's security failure. The general who had promised to lead from the front had instead presided over insecurity so pervasive that kidnapping for ransom - once confined to remote highways and troubled regions - had metastasised into a nationwide plague, with even previously secure states discovering they were merely awaiting their turn.

A man apart

What is to be said in his defence? Nowhere is the personal more political than in Nigeria, where the body politic is often literally embodied. There is no shortage of politicians who have simply refused to master their own flesh - men who lumber rather than walk, whose speech slurs with indiscipline, who cannot muster the basic courtesy of punctuality even for appointments they themselves have scheduled. Their bodies tell stories of perpetual capitulation, testament to every temptation indulged, every appetite fed. Against this backdrop of shameless surrender to impulse, Buhari stood apart like a reproach.

Though disease would cruelly ravage him during his first term, transforming vigour into frailty, his body had long told a different story - that of a man who had wrestled with temptation and won. After he returned from his extended medical leave in London, he seemed to have absorbed Dizzee Rascal's imperative - fix up, look sharp - into his very bones, appearing more polished and presidential than before his illness, as if proximity to mortality had refined rather than diminished him. He remained lean and ramrod straight, carrying himself with the contained stillness of a soldier who had never forgotten his first calling. At public functions, whilst others swam in their agbadas or slouched through ceremonies, he projected an almost ascetic composure, embodying the dignity that many Nigerians crave in their leaders even if they cannot quite articulate the yearning. In him, they saw what they wanted: living proof that self-mastery was possible, that Nigeria need not always be governed by men who could not govern themselves.

Even the mundane machinery of government seemed to respond to this discipline. Federal civil servants - long accustomed to the anxious wait for delayed salaries - found their pay arriving with clockwork regularity. Pensioners received their due without the usual genuflections and bribes. These were small mercies, perhaps, but in a nation that has never been able to take even the quotidian for granted, they mattered. He left his ministers largely unmolested, a courtesy so rare that one who served under him would later tell me with genuine pride that Buhari had never once asked him for a favour or applied pressure for personal gain. His sobriquet "Mai Gaskiya" - the honest one - was not, it must be said, without some merit. Here was a man who had indeed mastered himself, even if he would prove catastrophically unable to master the nation he had been privileged to lead on two separate occasions.

And yet, in the final accounting, perhaps no Nigerian benefitted more from Nigeria than Buhari himself. A ward of the state from his youth in military barracks to his burial in Daura, he drew sustenance from the nation for six unbroken decades. He came, he saw, and he took - not once, as conquerors do, but perpetually, insatiably, even unto the futures of millions whose destinies he irrevocably altered. A generation now wanders in the economic wilderness he created, their possibilities foreclosed, their horizons shrunk to the dimensions of daily survival. They will spend their prime years not building but recovering, not advancing but merely trying to return to where their country stood before he took the helm. And while they struggle with this inheritance - a legacy of magnificent self-regard masquerading as selfless service - he rests undisturbed in Daura's dust, his account with Nigeria settled entirely in his favour, his peace perfect and permanent, his victory complete.

Sai Buhari

Muhammadu Buhari, military dictator and twice democratically elected President of Nigeria, died on 13th July 2025. He was 82.

This is brilliant and apt. You've put into words some things I've thought but didn't quite know how to articulate.

I really don’t understand how this man could be seen as disciplined. A false perception, and it’s that perception that elevated him to the status enjoyed. What exactly were the principles that supposedly defined his discipline? I recently found out that he only joined the military to avoid being married off early, not out of any deep values or strong sense of purpose. He was a simple-minded man. As you've said, he lacked intellectual depth and very likely fits what we now understand as someone on the autism spectrum - narrow interests, rigid thinking, and poor social awareness,….. - not some kind of fake enigma. That an entire nation couldn’t see through him is perhaps the clearest sign of how lost we are -especially in Northern Nigeria. Well, I say Northern Nigeria but then there’s the Ronu posse.