F.O.O.D In Plain Sight: Defensive Capacity

The Nigerian cement industry is a cartel operating in plain sight. Here's how to fix it

During a recent exchange on Twitter, I mentioned something about capacity underutilisation in the Nigerian cement industry. I had assumed this was common knowledge, but was surprised to discover that many people were not aware of it at all. This piece explains how the structure of Nigeria's cement sector has evolved - or rather, stagnated - over the past fifteen years. If you’re new to F.O.O.D, you can start with this primer that introduced the series.

Build It and They Won’t Come

The Nigerian cement industry suffers from what appears, at first glance, to be a very strange problem: structural underutilisation of installed capacity. It would be one thing if capacity had held steady while production lagged behind, but that is not what has happened. What makes this remarkable is that installed capacity has tripled while utilisation has remained stubbornly fixed at just over fifty per cent. How can this be?

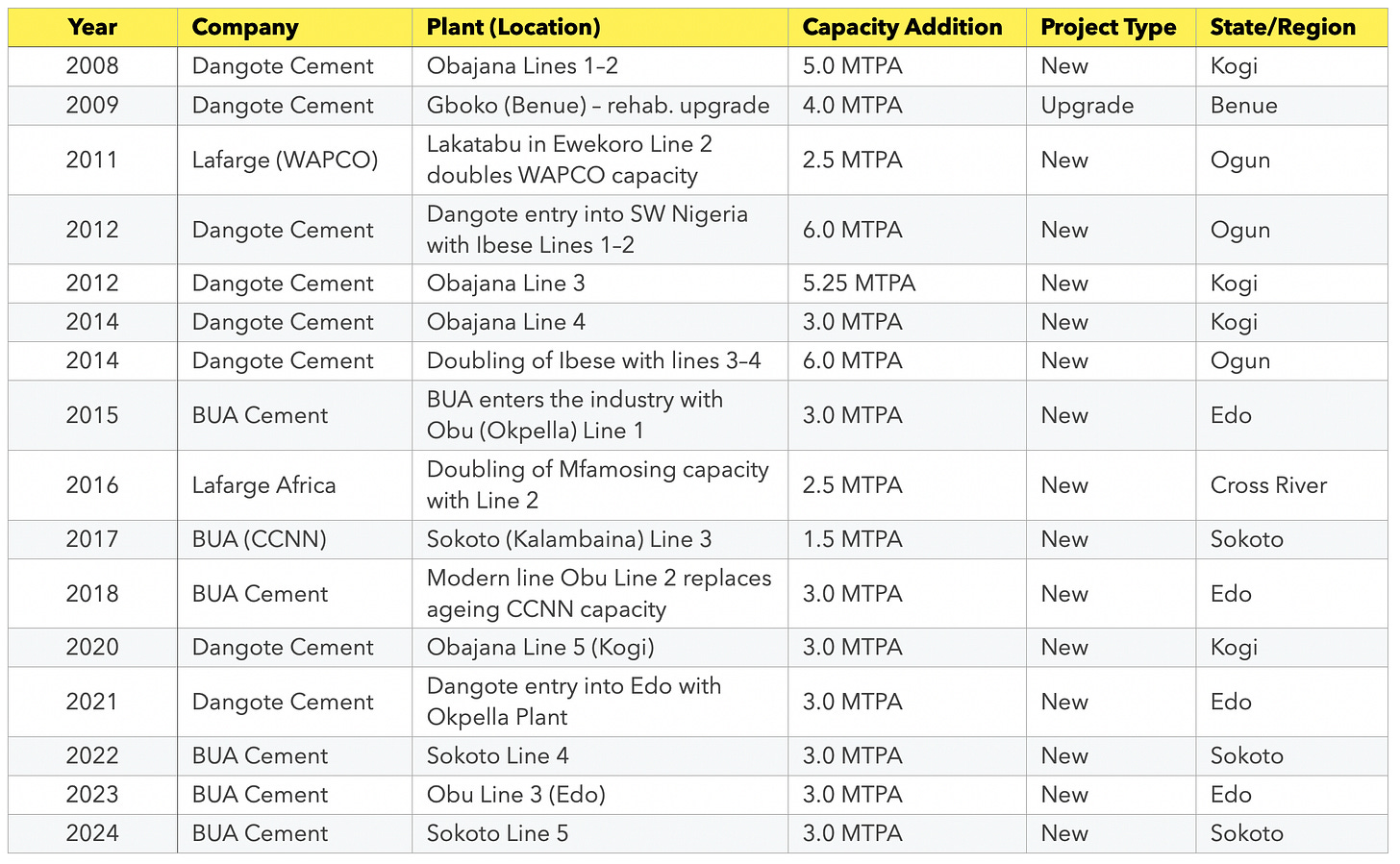

Before we get into what might be going on, here’s a brief timeline of capacity increase in the Nigerian cement industry since 2008:

Caveat: I've excluded additions below 1 MTPA as they're immaterial. Pre-2008 capacity data is incomplete, so the timeline begins with 2008. What I can find for sure is that as at 2010, Nigeria had around 16.5 MTPA installed capacity. When you take that 16.5 MTPA in 2010 (note that this includes the 9 MTPA installed by Dangote Cement in 2008 and 2009) as a starting point and add up everything since then, we end up with 64.25 MTPA as at the end of 2024.

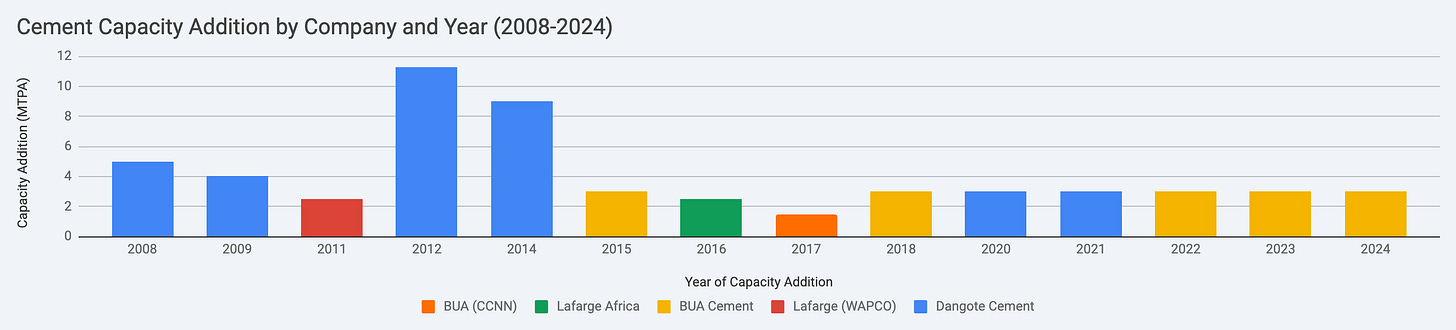

This is very impressive and has cost a lot of money. If you prefer to see the growth in bar chart form:

You can see that the big spike happened in 2012 and 2014 with Dangote. This sequence is also important as we shall soon come to see. We can also see that Lafarge has only added a total of 5 MTPA in two bursts of 2.5 MTPA. They are not stupid to ignore such a gold rush and this will also become evident as we go along. In total, Dangote has added 35.25 MTPA of capacity with BUA adding 13.5 MTPA.

Half-Tank Nation

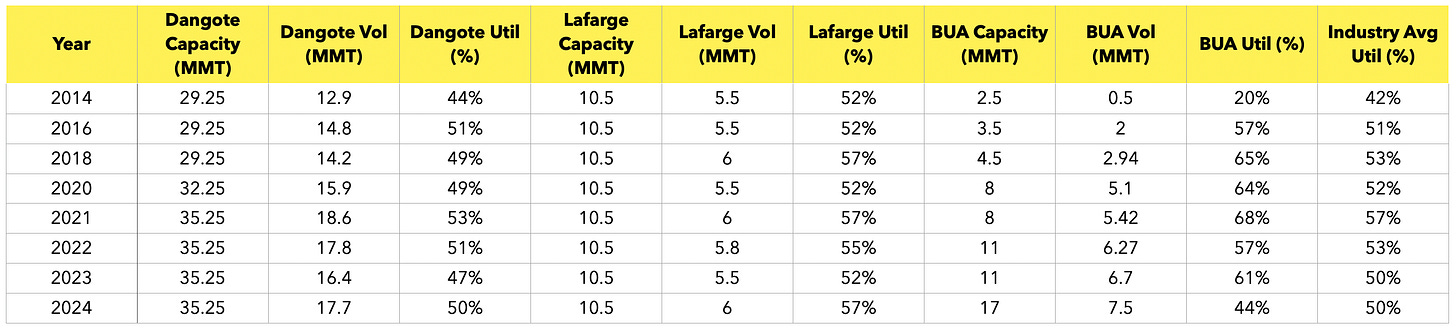

So how has all this capacity been used? I’ve pulled out information from their various annual reports which show what capacity they had at the time and how much they produced and sold from them:

There is a lot to unpack here so let’s walk through them step by step. A couple of years are missing (2015, 2017, 2019) but they are unlikely to materially change the trend we are looking at. Over the decade: Dangote averaged 49% utilisation, BUA 55%, Lafarge 54% - an industry average of 51%.

Between 2014 and 2024, Dangote’s volume produced increased from a low of 12.9 to a high of 18.6 before falling back to 17.7, in other words a 37% increase in volume over the decade. Without adding capacity after 2014, Dangote would have produced all it sold. BUA's trajectory is starker: from 2.5 MTPA (2014) to 17 MTPA (2024) - a 580% increase. By 2022, BUA had already added enough capacity to hit 2024 volumes. Lafarge's restraint - unusual for a multinational with global experience - is instructive. They simply produce about the same amount each year and ignore capacity building. Once again, they are not stupid for doing this.

In spite of this, more capacity is still being added. In July this year, BUA announced new 3 MTPA plant in Edo to come online in 2027. Before that, in March, Dangote announced a new 6 MTPA plant in Ogun state to be completed in November 2026.

What Cement Wants

The obvious head-scratching question here is: what is the point of adding all this capacity only to use half of it? How does capacity utilisation stay constant over a decade regardless of how much capacity is installed? We can answer these questions in part by looking at Nigeria’s per capita cement usage over the same time period.

Start with a report from the Oxford Business Group published in 2014 which said the following: “Nigeria’s per capita cement consumption was 126 kg in 2013, compared to a global average of 510 kg, according to the Global Cement Report 10th Edition, published by International Cement Review on March 31.”

Fast forward to the 2024 Nigerian Cement Industry Report published by Agusto & Co and we get this: “In 2023, the supply of cement in the Industry, represented by sales of the industry majors, declined by 5.2% year-on-year to 28 million metric tonnes (MMT) due to the slowdown in demand during the review period.” Dividing 28 MMT by 220 million yields 127 kg per capita - essentially flat from 2013's 126 kg. In effect, a decade of running to stand still. A report from Germany’s Wuppertal Institut produced in 2023 offers corroboration. It said: “The results show that in all scenarios Nigeria's demand for cement triples by 2050. However, due to the strong population growth, demand per capita grows only by 27 per cent to 151 kg per capita in 2050, which is still significantly lower than the value in other emerging economies.” Assuming a 2023 baseline to reach 150 kg by 2050 implies roughly 119 kg per capita today - worse than Agusto's estimate.

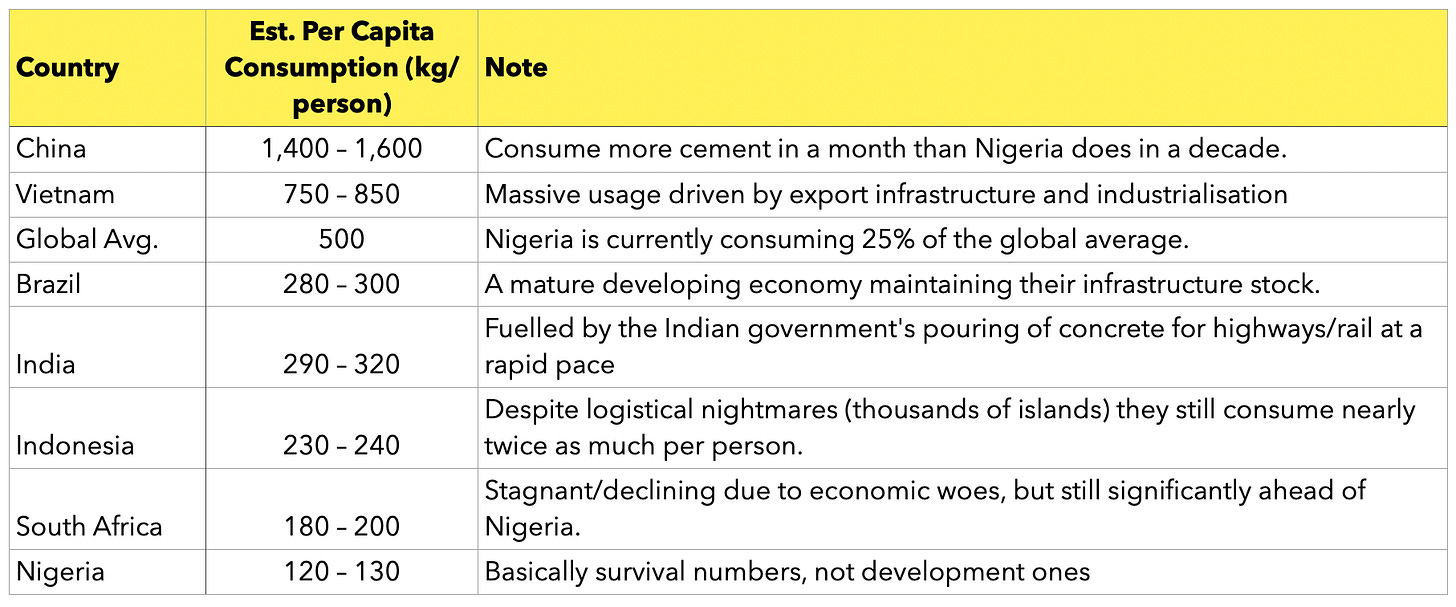

By any measure, these figures are dire. Nigeria's cement consumption suggests a country in survival mode - using just enough to avoid collapse. I pulled together some per capita numbers from across the world to illustrate the point:

If Nigeria reached eighty per cent utilisation - 51.4 million tonnes per annum - it would match Indonesia, approach India, and exceed South Africa. To give a sense of what that might look like in practical terms, here is a line from The Economist in 2023: "Indonesia has built 18 ports, 21 airports and 1,700km of toll roads since Jokowi took office. India is adding 10,000km of highway each year." If infrastructure development on that scale ever came to Nigeria, no one would need to announce it - to borrow from Davido, you will feel it.

Cement is a wonder of the modern world and there is no path to development that does not involve consuming lots of it. A country that stays stagnant in cement consumption for a decade is simply not developing, period.

House of Cards, Bags of Cement

This leads us to the main question of this piece - why on earth is Nigeria consuming so little cement when it already has the capacity to consume a lot more? The temptation is to say that it is because cement is too expensive. Without a doubt cement costs way too much in Nigeria - a tonne of cement in China costs $50 while the same thing costs around $140 in Nigeria. If people who are much poorer than their peers are having to pay almost 3x more for the same item, they will surely consume far less of it.

The question that needs answering remains: why does idle capacity persist when using it would lower prices? Before answering this, it is useful to stress that cement's unique properties triggers different regulatory approaches than other commodities. Back in 2014, Sonya Branch, who was at the time the Enforcement Director at the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) gave a speech about how the CMA, armed with enhanced investigative powers, intended to behave like a mainstream criminal enforcement agency, making detection, prosecution and punishment of hard‑core cartels significantly more likely.

Halfway through the speech in a section about cartel red flags she said this (emphasis mine):

In terms of detecting cartel activity, experience shows that this risk lies in a number of common situations, namely:

in sectors that are in decline

where there have been changes in market conditions, for example, where a new business enters a sector or where there are unexpected rises in input costs

in sectors where ‘everyone knows each other’

in public procurement processes, which can be vulnerable to bid rigging

In addition, many cartels have been found in the construction and transport sectors, and in other such basic or heavy industries (for example, chemicals, ball bearings and cement), in a number of jurisdictions.

In short, cement is notoriously cartel-prone. The reasons are straightforward: barriers to entry are high so you will only ever have a few players in a country (unless you are China, of course). The product itself also has a very low weight-to-value ratio: a bag of cement is almost worthless on its own for doing anything useful and yet it weighs 50 kg. Cement only becomes economically useful at scale. This means that transportation costs are a big factor in determining where it is produced and consumed. Thus, even though prices are in China are about a third of Nigeria’s, by the time you add transportation costs, the China product will work out more expensive or at best the same. The implication here is that a cement producer in Nigeria is naturally defended from competition: it cannot be smuggled and importing it will make almost no financial sense. The only competition you have to worry about is the one within your borders. And if there are only 3 or 4 of you, well what is the logical thing to do? Your guess is as good as mine. That is the point of Sonya Branch’s “everyone knows each other” comment and why she specifically name-checked cement in her speech.

When you look at the way Dangote has expanded capacity (paired with a map of Nigeria), the pattern becomes clearer: expand the existing plants in decisive step-changes while adding plants to complete national coverage. Obajana, the flagship, has grown line by line - from 5 million tonnes to 10.25 million in 2012, then adding another 3 million in 2014 and again in 2020, until it now sprawls across five lines with 16.25 million tonnes of capacity. Ibese was commissioned at 6 million tonnes and promptly doubled to 12 million. Okpella arrived in 2021 as a 3-million-tonne integrated plant in Edo State. The portfolio dominates Nigeria's major demand zones and transport corridors. The strategy is unmistakable: control delivered cost through logistics and render new entry economically unattractive across all significant regions (it is perhaps worth clarifying that I’m not suggesting that the company has committed a crime by pursuing a market dominating strategy).

This answers a common question about Dangote's strategy. Consider this thought experiment: you propose a cement plant investment to your bank. After you sketch your location strategy, the banker asks the killer question: 'What's your strategy against the industry’s excess capacity? The incumbents will open the taps and flood your market the moment you cut the ribbon on your plant. You'll be bankrupt before you pay your first supplier invoice’. At which point it becomes impossible for you or your bankers to make any money.

We have arrived at the number one reason for why all that unused capacity is being added by the incumbents: to make Nigeria look “un-enterable”. What Dangote and BUA are effectively signalling is “If you enter, we can flood your target region and crush price and we can outlast you because we’re diversified and already amortising assets.” Obtaining finance to compete against guys with spare 50% capacity ready to unleash on a new entrant will be close to impossible. Again, ask your banker. And I said earlier, Lafarge are not stupid for not playing this game. They are a multinational and their goal is simply to make money and avoid offending the local champions who are two very well connected dollar billionaires several times over.

This is Defensive Capacity.

(Un)Stable Geniuses

This brings us to the second reason for all that spare capacity. The popular image of cartels and oligopolies is one of cosy arrangements between pals who fleece customers until a regulator intervenes, but reality is rather different: cartels are inherently unstable, and their members spend considerable energy trying to undermine and cheat one another. George Stigler's authoritative 1964 paper on oligopolies - work that helped earn him the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1982 - argued that the real problem with cartels is not agreeing on a price but policing whatever agreement they reach. Stigler shifted the analytical focus from collusion to detection, demonstrating that cartels are unstable precisely because secret price cuts are highly profitable and difficult to spot. This, he explained, is why oligopoly members are so ostentatiously transparent with their prices, publishing and announcing them for all to see. The next time you hear of Nigeria’s cement players publicly declaring their prices, understand that they are doing it as much for each other as they are for you.

This is where idle capacity becomes very useful as a policing mechanism. In a concentrated market like Nigeria's cement industry, the players need not sell everything they can produce to maximise profit - they maximise profit by keeping prices high and avoiding price wars. If anyone breaks ranks to gain share via price cuts, rivals can swiftly punish the defector - ramping output or shifting supply to flood the zone until the rebel capitulates. Once again, the behaviour of Lafarge, as a multinational that cannot afford to get into political trouble in Nigeria, and avoiding the capacity games, is telling.

A few years ago, Nigeria’s lawmakers came painfully close to getting it. The Senate in 2021 adopted a motion calling for the relaxation of licensing restrictions to drive down cement prices. They said this (emphasis mine):

Lawmakers on Tuesday criticised the dominance of three large firms in Nigeria’s cement industry amid price rises they said impedes construction critical to economic recovery, calling for looser licensing rules to attract new entrants.

Nigeria has total cement production capacity of 47.8 million tonnes and annual demand for around 20.7 million tonnes, but cement prices are some 240% above the global average, they said, a serious dampener on Africa’s largest economy. A tonne sells for up to $135 in Nigeria, industry data shows.

Lawmakers have challenged cement price hikes since 2016 given the dominance of Dangote Cement (DANGCEM.LG), founded by Africa’s richest man Aliko Dangote, which has 60.6% market share. Lafarge Africa (WAPCO.LG) accounts for 21.8% while BUA Cement (BUACEMENT.LG) has 17.6%.

In a motion adopted in the upper house Senate, lawmakers called for a relaxation of licensing restrictions to create the competition needed to drive down prices.

They warned of the negative impact of high prices on the Nigerian economy, which emerged from recession in the 2020 fourth quarter but is grappling with double-digit inflation and a shrinking labour market amid mounting armed violence.

“The recent increase in the price of cement slowed down the amount of construction work being embarked upon...and almost collapsed the procurement plan of the government in 2020,” the motion said.

Their point about cement prices nearly collapsing government procurement is an intuition that finds support in academic research. A 2021 paper from Trinity College Dublin on the role of cement in development stressed that many low-income countries import machinery but must produce structures at home, leaving government and private investment in infrastructure - roads, bridges, ports, dams, public buildings - acutely exposed to domestic cement pricing. The authors show that cement's share of construction expenditure is far from trivial: the median country spends about 8% of construction outlays on cement, and countries at the seventy-fifth percentile spend more than 17%. The highest shares are concentrated in poorer nations, predominantly in Sub-Saharan Africa.

And what happened after that? Nothing, of course.

The Bag Also Rises

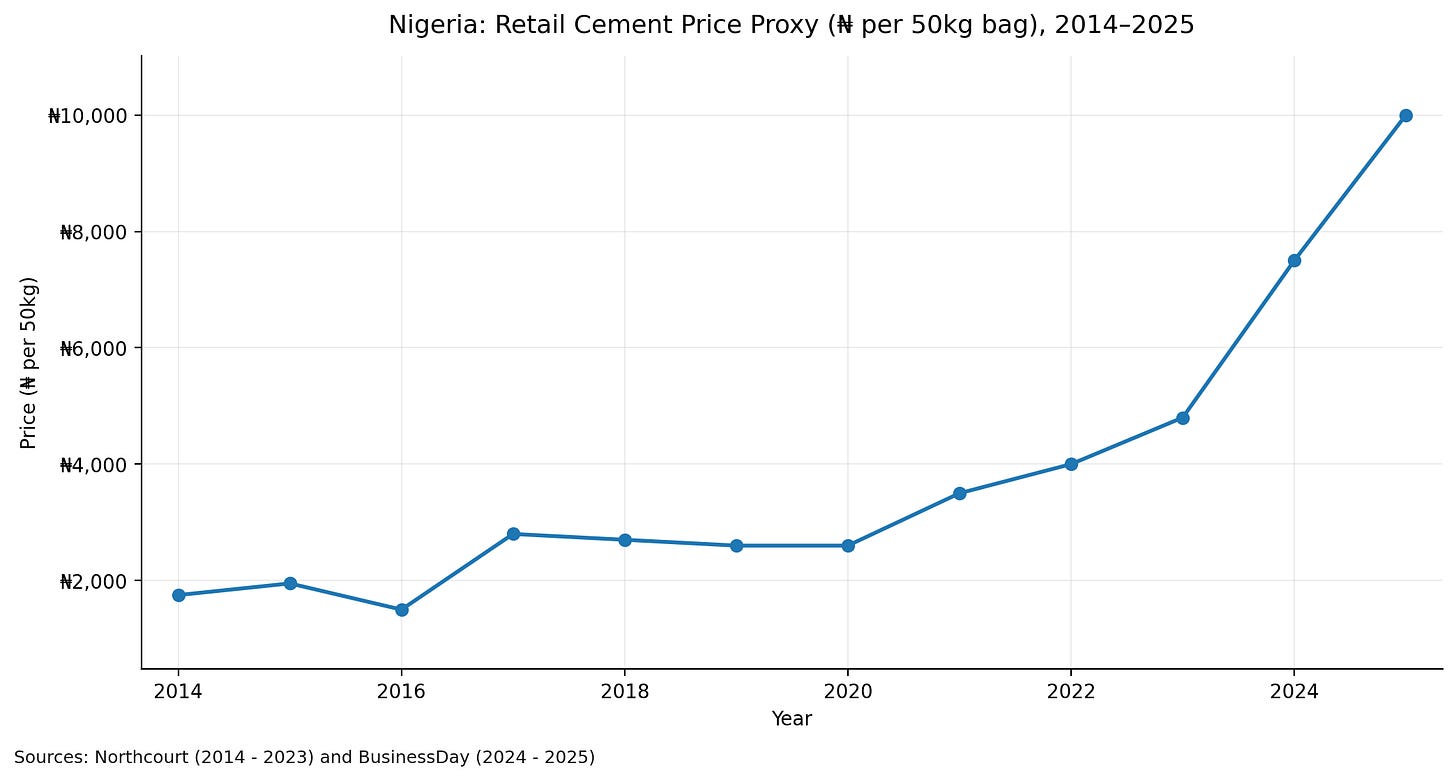

For reasons best known to them, the Nigeria Bureau of Statistics (NBS) does not include the price of a bag of cement in any of its commodity indices. This makes tracking the price of cement in Nigeria over time a challenge. To get around this, I have tried to come up with an index using a couple of sources. A company called Northcourt Real Estate periodically publishes a Nigeria Real Estate Review. Included in the report is the cost of building materials which includes a 50 kg bag of cement. I was able to find this data for 2014 to 2023. To get 2024 - 2025, I added BusinessDay market surveys as published in their paper. Caveat: the retail proxy used here means the figures may skew towards major cities.

A great deal happened over the decade shown in the chart - inflation was persistently high, and Nigeria endured multiple bouts of its perennial currency devaluations. We need some way to measure what a bag of cement costing ₦1,750 in 2014 meant relative to the same bag costing ₦10,000 in 2025. The most obvious proxy is the minimum wage. In 2014, the statutory minimum wage of ₦18,000 per month was enough to buy 10.3 bags of cement; in 2025, the minimum wage of ₦70,000 buys just seven bags. Of course, the minimum wage is not what most Nigerians actually earn - many receive less than the statutory floor - and at any rate, it is something that can change overnight with the President’s signature. So we need to test this against a more robust measure.

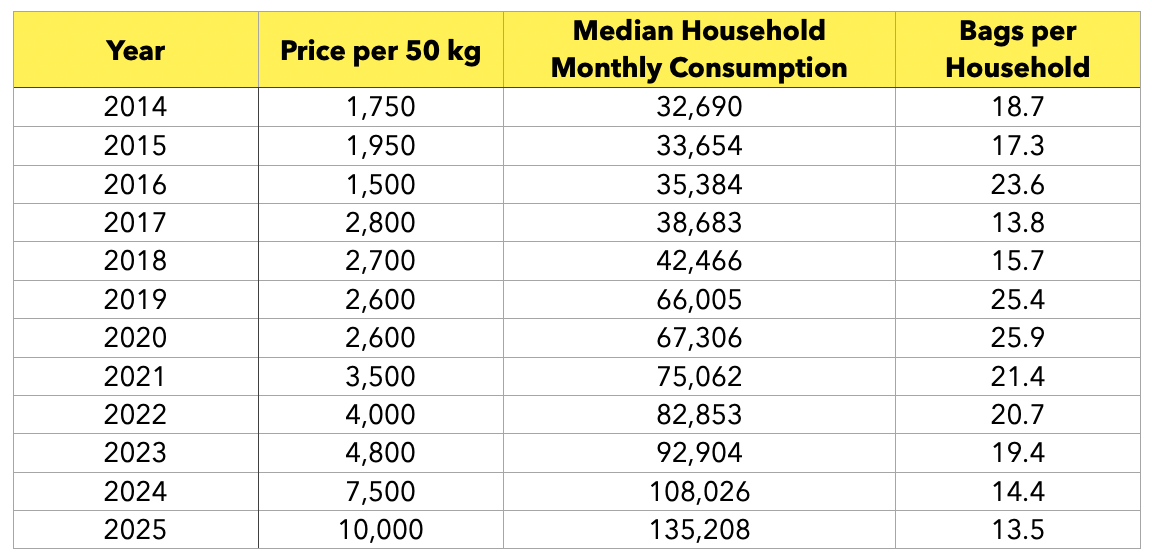

The NBS publishes the Nigerian Living Standards Survey, the official basis for measuring poverty and living standards. The most recent edition appeared in 2019, falling right in the middle of the time series constructed above. The survey reports five income buckets; averaging across them yields a mean per capita annual consumption of ₦192,632. To make the estimate more robust, we can convert this mean to a median (where half of Nigerians earn above and the other half earn below) using the Gini coefficient reported in the same document - 35.13. This implies a median-to-mean ratio of 0.813 (a bit complicated to explain but trust me on this one), giving us a median annual consumption of ₦156,533 (₦192,632 x 0.813).

Finally, since we used the monthly minimum wage as our first proxy, we should convert this figure to monthly terms as well. The NBS reports that the average Nigerian household comprises 5.06 people. Given that our figure is per capita, we multiply by household size and divide by twelve to arrive at a median monthly household consumption of ₦66,005 in 2019. But how do we extend this figure across the full decade from 2014 to 2025 to assess cement affordability over time? There is no perfect method, since we lack comparable NLSS data for other years. We must therefore rely on GDP per capita growth to scale the number backward to 2014 and forward to 2025.

Thankfully this is fairly straightforward to calculate using the World Bank’s GDP figures for Nigeria and the same World Bank’s population estimates for the country (If you are unhappy with my reliance on all these proxies, take it up with a country that has refused to conduct a census since 2006). You’re probably getting bored now so I will go straight to the final numbers which look like this:

There are many ways to quibble with this approach - household size may not remain constant over a decade, GDP per capita is not the same thing as household consumption, and so on - but the direction of travel is difficult to ignore. In 2014, a median household could, in theory, have devoted the equivalent of one month's consumption to cement and purchased 18.7 bags. In the intervening years, whenever economic growth raised consumption power high enough to afford more cement, the producers used their pricing power to swiftly put consumers back in their place. By 2025, the figure had fallen sharply to just 13.5 bags. The story is straightforward: the price of cement has grown faster than household spending power and GDP per capita. And given how critical cement is to economic growth, this raises a chicken-and-egg question worth pondering: the economy cannot keep pace with the growth in cement prices because the growth in cement prices slows down the economy.

The immediate response one typically hears when raising the question of cement prices is that in dollar terms they have remained broadly constant - as if that settles the matter. Leave aside the fact that it is far from obvious why Nigerian cement prices should track the exchange rate so closely when the inputs are almost entirely localised. The more fundamental point is this: we are dealing with an industry whose dominant player, Dangote, can push through whatever price increases it wishes, for whatever reason, because market concentration and the nature of the product itself mean that consumers have nowhere else to go. And I cannot stress this enough - these price increases are happening in the context of deliberately restricted supply.

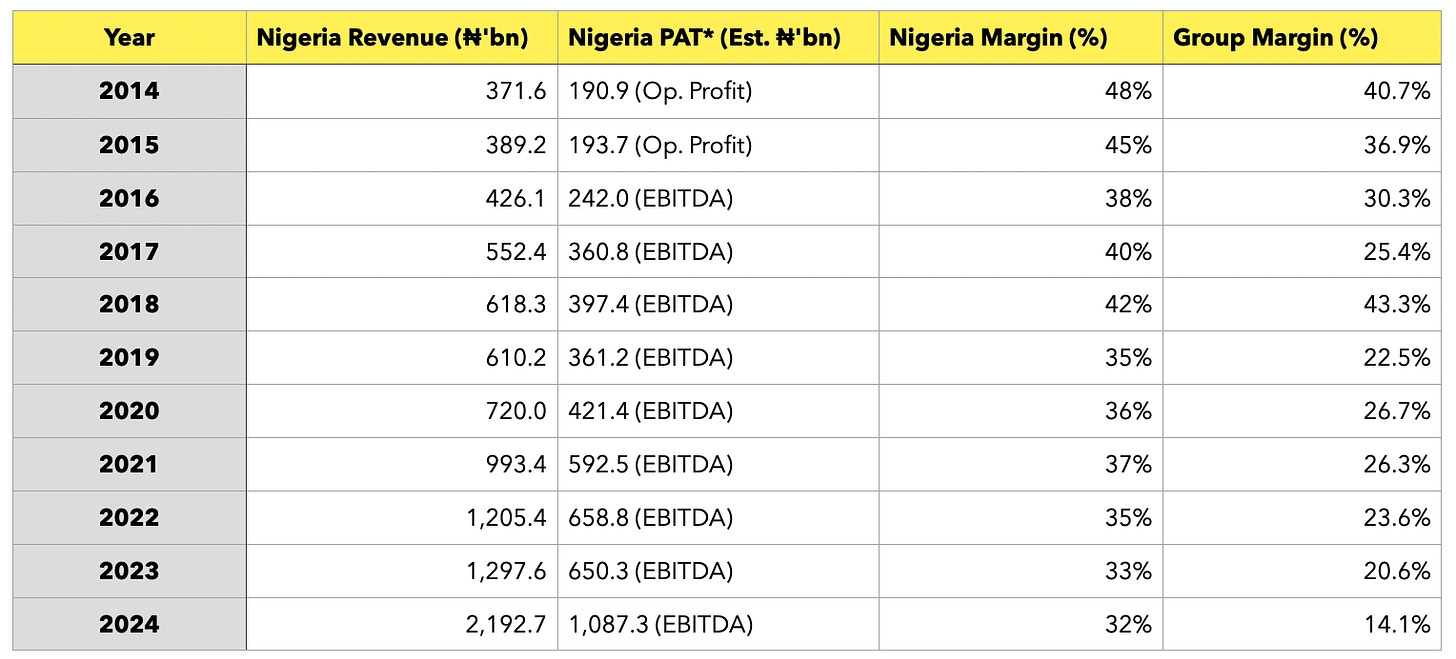

Here it is important to remind you, dear reader, that Dangote Cement, on a net profit basis after cost of production and cost of borrowing have been accounted for, is the most profitable cement manufacturer in the whole world.

I put together a table of Dangote Cement’s profit margin over the 2014 - 2024 period:

Dangote Cement reports operating profit or EBITDA at the Nigeria segment level, but net profit is typically disclosed only at the group level (I suspect this is deliberate), reflecting centralised finance costs and tax structures. The Nigeria margin estimates above therefore rely on segment EBITDA and operating margin trends, while the group margin represents the precise audited net profit margin.

Regulators Assemble

Given how dismal all of this sounds, you may be surprised to learn that there is a positive dimension to the story. Unlike many of Nigeria's other intractable problems, this one is not as bad as it seems - precisely because nothing I have described is unique to Nigeria. This pattern of behaviour, as Sonya Branch's remarks made clear, follows the cement industry around the world. Left to their own devices, cement players will reliably produce the state of affairs described so far. It is for exactly this reason that regulators elsewhere have learned to take a more muscular approach when dealing with the industry. Let’s step through some examples.

India

In July 2018, India’s Company Law court delivered judgement in favour of the Competition Commission of India (CCI) in the case it brought against India’s cement manufacturers. CCI argued (among many other things) that in late 2010 the cement companies simultaneously reduced production and distribution (notably November–December 2010) despite rising demand from the construction sector, and then raised prices sharply in early 2011, evidencing a coordinated supply restriction to facilitate higher prices. Overall capacity utilisation in 2010‑11 dropped to about 73%, compared to higher levels in prior years, despite capacity growth and healthy demand, which CCI viewed as inconsistent with purely competitive behaviour. That sudden drop in capacity utilisation triggered swift regulatory action.

All appeals by the cement companies were dismissed by the court, and CCI’s 31 August 2016 order - finding contraventions, directing cease‑and‑desist, and imposing penalties - was upheld in full. The 11 cement companies were directed “to cease and desist from indulging in any activity relating to agreement, understanding or arrangement on prices, production and supply of cement in the market”.

CCI imposed monetary penalties on each cement company at 0.5 times its net profit for the relevant period (2007–08 to 2010–11), and on the Cement Manufacturers Association (CMA, they had been using the trade body to disguise their data sharing) at 10% of its average receipts for three years.

This case has become the gold standard that shows that capacity underutilisation is a form of cartel behaviour.

South Africa

This case is an interesting one in that there had been an officially allowed cartel before 1996, exempt from competition law. Anticipating its end, producers agreed in 1995 to maintain their existing market shares. After the official cartel was disbanded in 1996, a price war broke out, leading producers to meet in 1998 to “stabilise” the market, from which the illegal cartel arrangements emerged.

The Competition Commission (CC) initiated a sector investigation in June 2008 after a study on construction and infrastructure inputs. At this point, one of the cartel members - Pretoria Portland Cement (PPC) - agreed to snitch on the others by providing all the information on their activities to the CC.

While the decision doesn't explicitly mention capacity underutilisation, its references to “scaling back of marketing and agreed depot closures” imply deliberate output restriction. The Commission estimated the overcharge and consumer harm using a “during‑and‑after” econometric model on cement prices from January 2008 to December 2012 and calculated that consumer savings from the Commission’s at about R4.5 - R5.8 billion for 2010 - 2013 (based on avoided future cartel pricing). Had the Commission successfully broken the cartel from 2000, estimated consumer savings over 2000 - 2013 would have been roughly R14.9 - R19.3 billion.

Brazil

The Brazil case offers perhaps the closest parallel to Nigeria. CADE - the Brazilian regulator - specifically found that the cartel managed supply to inflate prices, which effectively amounts to strategic underutilisation. However, they used slightly different legal terminology. Instead of just calling it “underutilisation,” CADE ruled that the companies engaged in “fixing sales quantities” (quotas) and “restricting output” to match those quotas.

CADE found that the six major companies were not just setting prices; they were deciding exactly how much cement each company was allowed to put into the market. The cartel allocated "market share quotas" to each member. If a company could produce 1M tons but its quota was 800k, it deliberately ran below capacity to avoid price collapses. CADE seized documents showing the companies exchanged monthly data on production and sales to ensure no one was "cheating" by producing more than their agreed limit. The investigation noted that holding excess capacity was also used as a threat. If a new competitor tried to enter the market, the cartel members could suddenly "turn on" their idle capacity to flood the local market and bankrupt the newcomer - exactly as we discussed earlier.

CADE did not just fine the companies, it forced them to sell 24% of their capacity to a new market entrant. CADE realised that as long as these companies held so much unused/dominant capacity, they would always have the power to manipulate supply. The only way to fix it was to take the factories away from them and give them to someone who would actually run them to compete.

Germany

In April 2003, Germany’s Federal Cartel Office (Bundeskartellamt) imposed fines totalling €660 million on the six largest cement manufacturers - HeidelbergCement, Lafarge, Schwenk, Dyckerhoff, Alsen (Holcim), and the "spoiler" Readymix (a subsidiary of the British firm RMC, now part of Cemex). They were found to have divided Germany into four regional monopolies (North, South, East, West) and assigned strict quotas based on historical market share. If you sold more than your quota, you had to buy cement from a rival to "balance" the books.

What made the cartel “unstable” was Readymix. It had aggressively expanded its production capacity (especially in East Germany after reunification) but was locked into a historic quota that was too small for its new factories. To solve its underutilisation problem, Readymix started secretly selling excess cement to non-cartel independent ready-mix concrete producers at discount prices. When the other cartel members found out, they launched a "punishment" price war. Readymix, bleeding cash, eventually ran to the regulator and blew the whistle in exchange for leniency (it only got a €12 million fine) .

The more interesting and relevant part of this story is that it showed that capacity underutilisation is actually expensive. The way the German cartel members (who had already amortised their plants) got round this problem was by keeping German cement prices 30% above those in neighbouring countries. For Readymix which had only recently just spent money on new capacity, this was not enough and the temptation to cheat was very high.

China

China's approach differs markedly but offers instructive parallels. China has repeatedly used policy tools to restrict capacity growth in cement. Reuters reported a 2018 Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) notice saying cement capacity expansion would be “strictly off-limits,” and that even “necessary” projects must follow replacement rules so total capacity “only decreases and not rise.”

China's cement buildout was massive through the 2000s and early 2010s, fuelled by infrastructure and real-estate investment - including the surge that followed the 2008 - 09 stimulus. By the late 2010s, the industry itself was openly acknowledging the problem: one producer told Reuters that China could produce more than three billion tonnes, but "real" demand stood at just 2.2 billion. In an August 2018 notice from the MIIT and the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the preamble states - I paraphrase - that while the industry's condition had improved and operating quality had risen, "as profits improved, some places showed early signs of launching new capacity projects." The state must therefore tighten controls once more to "consolidate the gains" and prevent new capacity from emerging.

To reiterate, this was not a classic collusion case prompting regulatory intervention. The problem the Chinese government was trying to solve was very different. I share this example to show how far regulators can and will go when it comes to the cement industry. Banning capacity increase is almost unheard of in most industries but in cement, it is not unusual to see. Again, the nature of the product is what makes it so.

It remains a “live” regulatory with the MIIT only a few weeks ago ruling out any new cement capacity while vowing to continue regulating existing production and eliminating outdated and inefficient facilities.

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

It should now be clear what needs to be done. Cement is too vital to development to tolerate a pricing structure that captures all value at production, rendering downstream activity prohibitively expensive. But I will spell it out explicitly:

Creation of a new player in the market - Dangote, BUA, and Lafarge should be required to divest a portion of their existing capacity - at market price, without imposing a loss on them - to establish a new competitor, preferably one backed by Chinese operators with experience in competitive cement markets. This is not an outlandish proposal; regulators around the world have employed precisely this approach in cement. The new entrant should start with at least thirty per cent of market capacity and a geographical spread i.e. every region must have at least3 players present especially in the middle belt where rich limestone deposits are and is the logistics hub for the whole country. Enough must be carved out of the incumbents to give it approximately 19.3 million tonnes per annum from day one.

Lift the ban on imports - Importation of bagged cement into Nigeria has been prohibited for twenty years, and it is time to lift that restriction. To be absolutely clear: removing the ban will not, in itself, bring down prices or resolve the structural problems documented above - transportation costs alone would see to that. What lifting the ban can do is prevent situations like this year's, when Dangote unilaterally raised prices by more than forty per cent. Imports would act as a de facto price ceiling, constraining how far incumbents can push prices before foreign supply becomes attractive.

Introduce an explicit technology mastery requirement - I have documented elsewhere how Nigeria's cement manufacturers have failed to demonstrate that they have truly mastered the technology of cement production in a way that can be replicated without Chinese assistance. Two decades of policy protection and billions of dollars in profits ought to be sufficient to show for something. For cement billionaires to be signing contracts with Sinoma for operations and maintenance at this stage of the cement policy is nothing short of shameful. Any Nigerian-owned cement manufacturer should henceforth be required to demonstrate genuine technological capability, and the requirement must carry real consequences for non-compliance.

Nobody is coming to save Nigeria from a situation it has allowed to develop on its own soil. Permitting imports will not solve the problem, for the reasons already stated. Listen for excuses about production and borrowing costs, but expect silence on why Nigerian margins exceed the world's. You will see attempts at deliberate confusion over exports - the usual charlatans standing ready to reverse-engineer some "strategic" justification for whatever Dangote does, lending a veneer of expertise to apologetics. Do not be distracted by any of this. Nigeria's cement industry is exhibiting precisely the pattern observed in country after country. The only difference is that no one, as yet, has summoned the will to do anything about it. Nothing you have read in this post is hidden - everything is publicly available information.

Focus. Look what cement can do

In today's edition of Nigeria is a normal country with not so good governance.

This is so good! But Nigeria is so difficult and so captured by greedy criminals that the chances of these ideas being adopted are extremely low. It’s so unfortunate because we literally could have good things if not for our greedy and myopic “great” men.