The Men Who Did Not Build Nigeria

A story of outsourced innovation and domesticated rent-seeking

For Tan Zhongming, the 2nd of September 2012 was a day like any other for a man defined by his formidable work ethic and dedication: it was spent on the road, championing the state-owned enterprise he had transformed into a global industrial titan. In Paris, during a pivotal investor roadshow, he collapsed and died from a heart attack. There is no record of the Nigerian government acknowledging his passing - an oversight of profound ingratitude, for no single individual did more to realise the country’s flagship industrial policy since the return to democracy in 1999. Tan Zhongming, more than anyone else, helped create the largest fortunes in Nigeria’s modern history, though he would never personally profit from them.

Born in August 1953 in Weifang City, a windswept coastal region of China’s Shandong Province, Tan Zhongming came of age during the upheaval of the Cultural Revolution. His career began early, at just fifteen, when he joined the state-owned Weifang Dongfeng Foundry. He later moved to the Weifang Chemical Reagent Factory, where he rose to become deputy workshop director between 1969 and 1975. When China reinstated its university entrance exams, Tan seized the opportunity, studying cement engineering at the Nanjing Institute of Chemical Technology from 1978 to 1982. It was there that he honed the technical expertise that would define his legacy.

Upon returning to Shandong after graduation, Tan began a methodical ascent at the Weifang Cement Plant, rising from a technical cadre to executive deputy plant manager between 1982 and 1990, before taking a post as deputy general manager of the Weifang City Building Materials Industry Corporation. In 1992, he joined the Shandong Lunan Cement Plant as an assistant, later becoming its executive deputy manager - a role that honed his operational and leadership prowess. A committed Party member since 1976, he was selected in July 1995 for a senior role at Beijing’s State Bureau of Building Materials. There, he shaped national standards and energy-saving policy while simultaneously completing an in-service Master of Science degree (1989–92) and a doctorate in Management Science and Engineering (1999). This rare fusion of hands-on experience, regulatory insight, and advanced scholarship paved the way for his critical appointment in October 2000 as general manager and deputy Party secretary of the newly formed China National Non-Metallic Minerals Group - the corporate precursor to Sinoma, the name by which the conglomerate is internationally known, derived from an abbreviation of its full Chinese title.

Sinoma, a short history

Before it became the global leviathan known as Sinoma, the China National Materials Group was an enterprise in distress. Formed in 1983 from the spun-off bureaus of a government ministry, its initial mandate was a broad and often unfocused mix of research, engineering, and trade in non-metallic materials. By the late 1990s, this lack of strategic clarity had pushed the group to the brink of collapse. A disorderly expansion into dozens of non-core business lines had left it burdened with debt and plagued by operational failures. Poor management had triggered internal unrest, and the sprawling conglomerate seemed to be a textbook case of a state-owned enterprise unable to adapt to China’s modernising economy.

The company’s technical foundation, however, remained its saving grace. Sinoma had inherited China’s premier cement and materials research institutes, repositories of decades of scientific R&D dating back to the 1950s. Yet this immense potential was squandered on peripheral ventures, leaving its core competencies in cement technology and engineering services underutilised and unprofitable. The group was haemorrhaging money, its intellectual capital lying dormant beneath a mountain of financial and managerial chaos. By the year 2000, the situation was critical.

It was into this crisis that Tan Zhongming was appointed. His task was to perform a radical rescue operation, forcing a bloated and failing administrative relic to become a streamlined, market-driven competitor. The survival of Sinoma depended on it.

Tan Transformer

Tan Zhongming’s prescription for Sinoma’s revival was a masterclass in strategic focus. He immediately initiated a brutal streamlining, jettisoning dozens of non-core businesses to concentrate the sprawling group on three pillars: cement engineering, non-metallic materials manufacturing, and mining. His most critical move was to consolidate the company’s scattered technical assets. Within his first month, he began merging several regional design institutes and construction units into a single, powerful entity: Sinoma International Engineering. Launched in 2001, this new flagship became the group’s dedicated vehicle for offering integrated EPC (Engineering, Procurement, and Construction) services, allowing it to design and build entire cement plants anywhere in the world. The personal toll was immense; colleagues noted that the stress of forcing through this reorganisation turned Tan’s hair from black to white in a single year.

The second phase of his strategy was to secure the capital for global domination. In 2007, Tan orchestrated a landmark initial public offering on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, raising HK$4.1 billion. This created a powerful dual-platform structure: the listed entity in Hong Kong handled financing and investment, while Sinoma International in Shanghai executed projects. The IPO was a resounding success, providing the war chest for explosive growth. From a modest revenue base of around ¥500–600 million, Sinoma International’s earnings skyrocketed, reaching ¥11.6 billion in the first half of 2012 alone. This financial muscle fuelled a relentless international expansion, transforming Sinoma from a domestic operator into the world’s undisputed leader in cement plant engineering.

Under his leadership, the turnaround was spectacular. He transformed a debt-laden, incoherent administration into a multifaceted industrial champion, executing hundreds of major projects across six continents. The company he inherited was on the brink; the one he left behind was a global titan, firmly holding the number one position in its field and standing as a cornerstone of China’s ‘Go Global’ initiative.

Beneath his unassuming and softly spoken demeanour, Tan Zhongming was a leader of immense resolve and quiet intellect. Colleagues described him as a man who let results, not words, do the talking; his style was methodical, solid, and devoid of any flashiness. This pragmatic approach was balanced by a scholar’s curiosity - he was a voracious reader of history and philosophy, often drawing lessons from biographies to inform his prudent leadership. His integrity was unwavering; he was known to insist that "standards are our industrial backbone – we cannot bend them," a principle that became the foundation of Sinoma’s global reputation for quality. Ultimately, his dedication was absolute, a fact underscored by his final act: tirelessly championing his company’s prospects to investors on a roadshow in Paris, working until his very last breath.

It was a profound symmetry that in 2005, Tan Zhongming was named a National Model Worker, an accolade that placed him in a lineage of legendary Chinese industrial pioneers. The award’s history is steeped in the ethos of self-sacrifice and superhuman effort best exemplified by figures like Wang Jinxi, the “Iron Man” of the Daqing oil field. During China’s desperate push for energy independence in the 1960s, Wang famously mixed cement with his own legs to avert a catastrophic blowout, an act that became a national symbol of unstinting dedication. In receiving the same honour, Tan was recognised as a modern inheritor of this same spirit - a visionary who, through intellectual rigour and strategic genius rather than physical force, had nonetheless performed a similar feat of national industrial strengthening. His award thus connected the gritty heroism of China’s past to the sophisticated global leadership of its present.

Nigeria and Cement

Nigeria’s Backward Integration Policy (BIP) for cement, launched in 2002, was born from a place of economic necessity. With over 70% of its cement needs met by costly imports, the country was haemorrhaging foreign exchange. The policy’s logic was protectionist and straightforward: to obtain a licence for importing cement, companies were required to prove they were building local manufacturing plants. With incentives like duty waivers on equipment, the government aimed to catalyse domestic production, achieve self-sufficiency, and ultimately position Nigeria as a regional export hub, creating hundreds of thousands of jobs in the process.

On paper, the policy was a spectacular success. Within a decade, installed capacity skyrocketed from 4 million to 45 million metric tonnes per annum, transforming Nigeria from a net importer into a cement powerhouse. However, this narrow focus on capacity came with costly omissions. The policy was silent on critical issues like mandatory technology transfer, which would have ensured the local mastery of complex processes like clinker production. More significantly, it lacked any framework to link this industrial boom to tangible national development, with no binding targets for housing construction, infrastructure quotas, or measures to guarantee that increased supply would lead to cheaper prices for Nigerian consumers.

The implementation and ultimate beneficiaries of the policy, however, cannot be divorced from the political landscape. As recounted by Nasir el-Rufai in The Accidental Public Servant, industrialist Aliko Dangote’s prominence in governmental circles grew significantly after he allegedly financed President Obasanjo’s 2003 re-election campaign. This newfound influence coincided perfectly with the rollout of the BIP. For a businessman like Dangote, who had traded in various commodities, cement presented a uniquely attractive opportunity. Unlike sugar, flour, or other easily smuggled goods, cement is bulky, difficult to conceal, and requires significant logistics to transport legally or illicitly. A government ban on imports, enforced by customs, could therefore be remarkably effective at shielding the domestic market from foreign competition, creating a captive market for local producers.

Before the Backward Integration Policy could even begin to foster new production, it first had to address the decaying legacy of the past. Nigeria’s cement industry, once comprised of state-owned plants, was on its knees. From a peak domestic production share of over 80% in the late 1980s, local output had collapsed to 23.5% by 2002, supplanted by a flood of expensive imports. A crucial first step of the new policy was therefore the wholesale privatisation of these moribund government assets. Unlike in other sectors such as iron and steel, this transfer of ownership to private hands proved remarkably effective, injecting immediate life into derelict facilities and providing the established operational foundations upon which the new cement giants would rapidly build.

This flawed design and its political context created a perverse outcome. Rather than fostering open competition, the BIP entrenched a powerful duopoly. By restricting import licences to a select few with the capital and political connections to build plants, the policy effectively empowered major players like Dangote, and later BUA, while shutting out smaller competitors. As scholarly analysis reveals, this led to a market characterised by "significant behavioural complexity and strategic self-positioning" where major stakeholders manipulated the market to their advantage. The state, often captured by the interests of these cement cartels who wielded significant political influence, permitted this environment to flourish.

Consequently, the ultimate irony of Nigeria’s cement policy is that while local billionaires schemed to capture a protected market, an unassuming engineer in China, Tan Zhongming, was perfecting the very science that would enable their fortunes. There is no evidence that Tan, who worked until his dying day, ever accrued immense personal wealth from his labour. Yet, piggybacking on the transformative technology and global supply chains he built at Sinoma, billions of dollars would be made in Nigeria. The policy minted Nigerian oligarchs while the average citizen continued to pay some of the highest prices in the world for their cement - a testament to a programme that achieved its narrow goal of self-sufficiency through imported expertise, but utterly failed in its broader, unwritten mandate of national development.

Sinoma in Nigeria

Sinoma’s technological advancement arrived with a further layer of irony. Just as Nigeria’s policy-makers were designing a market to be captured by a few domestic oligarchs, Sinoma was perfecting a revolutionary cost-saving technology that ought to have been a boon to a poor and developing country like Nigeria: waste-heat recovery. After two decades of R&D, the company could now equip plants to generate up to half of their own electricity from excess kiln heat, dramatically slashing both production costs and carbon emissions. For a nation plagued by an unstable power grid and exorbitant energy costs, this would have been nothing short of a transformative solution. Yet, the beneficiaries of this scientific progress were not Nigerians, but the profit margins of the new cement barons, who imported this state-of-the-art efficiency to build fortunes on a foundation laid by Chinese engineering.

Despite the “localisation” of ownership and the massive expansion of capacity, the physical creation of this new industry was outsourced. Sinoma, through its subsidiaries like CBMI, has been the Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) contractor for nearly every major greenfield cement plant project in Nigeria since the mid-2000s, effectively building the very assets that would mint billions for local billionaires.

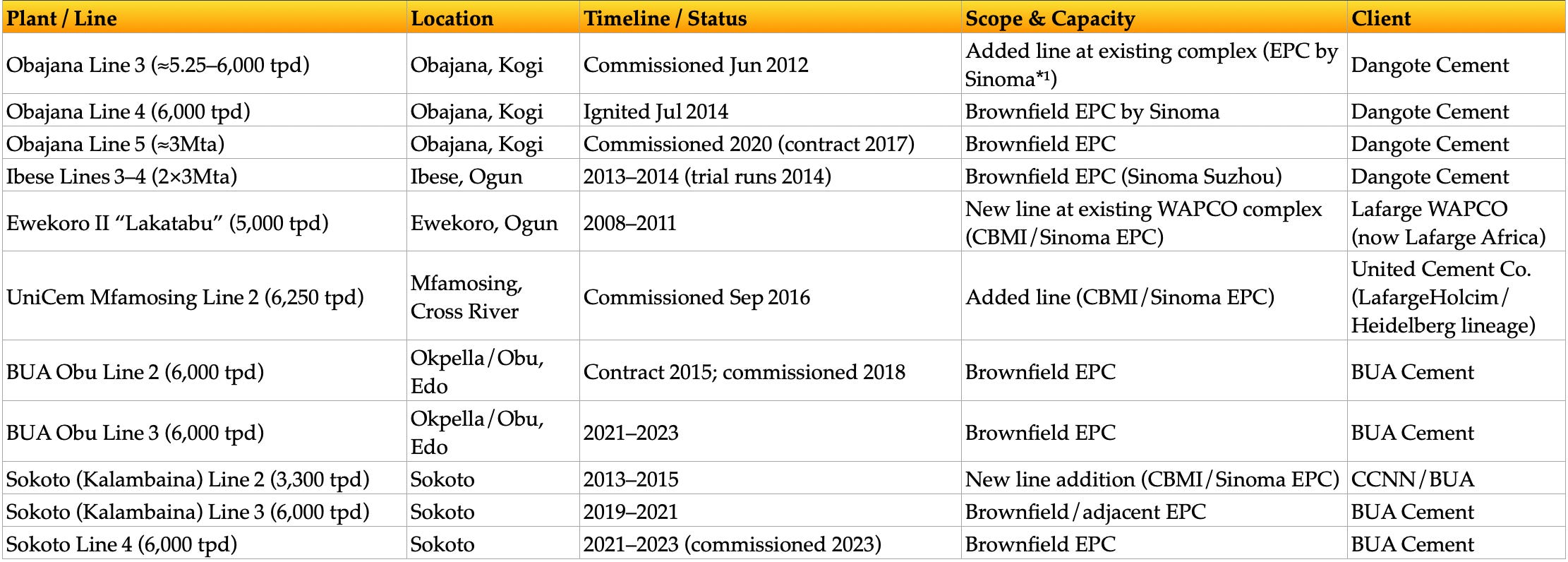

The following table chronicles Sinoma's near-total dominance in constructing Nigeria's new generation of greenfield integrated cement plants:

If mastering the complexity of greenfield projects could be considered an unfair expectation for a nascent industrial class, then the expansion and modernisation of existing plants - so called brownfield projects - should have offered the perfect opportunity for local expertise to emerge. Yet here, too, the story is the same.

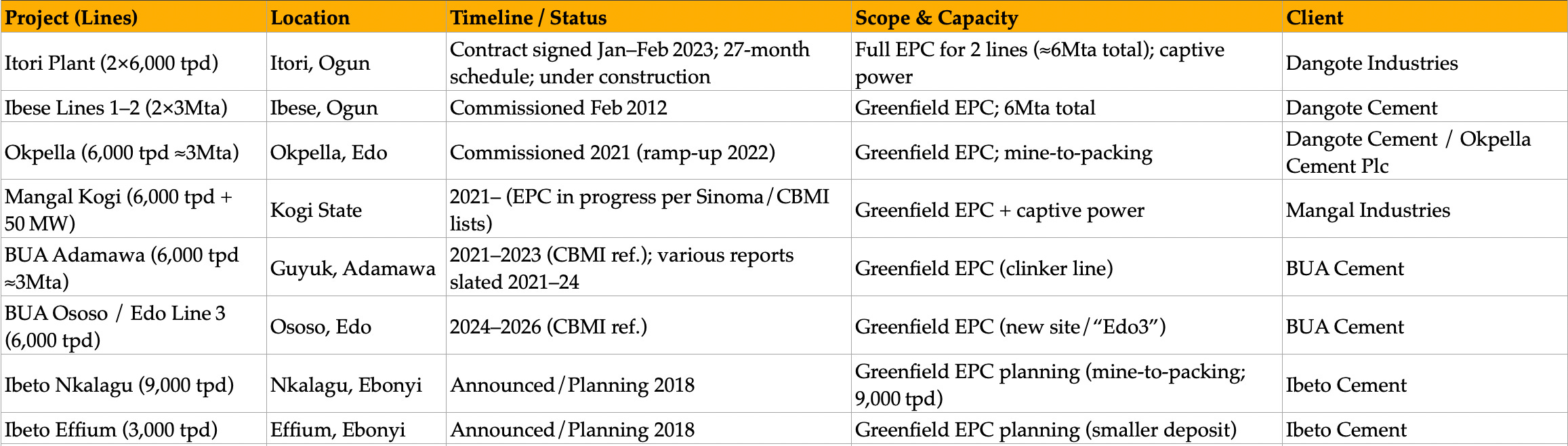

The table below again shows Sinoma’s near-total dominance in executing the major brownfield expansions for every significant player in the Nigerian cement industry, revealing that the reliance on its technology and project management is absolute, regardless of the project type or the client.

This dependency reaches its logical, and perhaps most damning, conclusion in the day-to-day operation of the industry itself. If building new plants and expanding existing ones represents the high-end of engineering, then the ongoing operation, maintenance, and logistics of these facilities should be the natural domain of the local owner. Yet, even here, after two decades of the BIP, there is no evidence of a meaningful transfer of operational mastery. Sinoma’s involvement is total, extending deep into the mundane but critical heart of production. The company is not just the builder but the permanent custodian, securing contracts for everything from quarry management and emissions upgrades to grinding mill optimisations and even customs clearance for imported equipment. Below this level of basic plant husbandry and logistics, there is simply no lower to go.

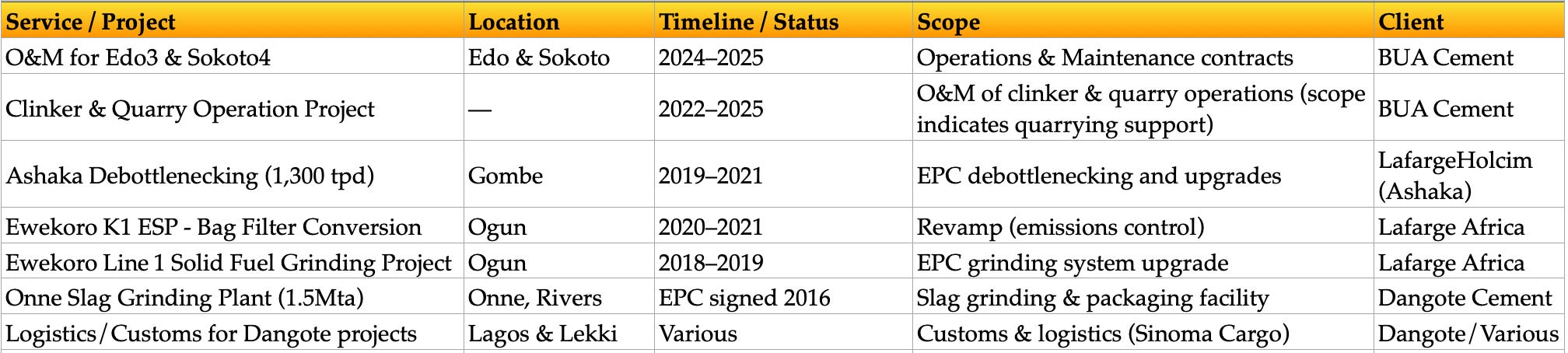

This final table illustrates this operational reliance, revealing an industry where Nigerian billionaires enjoy the margins of manufacturing while a Chinese state-owned enterprise ensures the machines actually run.

From the construction of every major greenfield plant and brownfield expansion to the ongoing operations and maintenance of these facilities, Sinoma’s technological dominion over the Nigerian cement industry is near-total. To be clear, this is not an argument against the use of foreign technology; the Chinese themselves are the first to admit their own development was built upon adopting and adapting foreign expertise. The argument here is against a demonstrated lack of mastery, a complete absence of innovation, and, worst of all, a regulatory and societal environment that places no demand on local firms to do so.

The Nigerian cement barons operate as if the mere acts of building capacity and producing cement within national borders are the ultimate objectives. What Nigeria has allowed to happen is a ridiculous situation: the innovation - the critical, value-creating process that produces society-wide benefits and constitutes the body of knowledge a nation can claim to know - has been entirely outsourced. Meanwhile, the manufacturing of billionaires has been thoroughly domesticated.

Too much to ask for?

Is this really too much to ask for? To find an answer, it is useful to compare Nigeria’s trajectory with that of other nations which also began by borrowing technology, yet consciously climbed the value chain through the deliberate mastery of it. An instructive example comes from South Korea’s period of late industrialisation, meticulously documented by Alice Amsden in her seminal work, Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialisation.

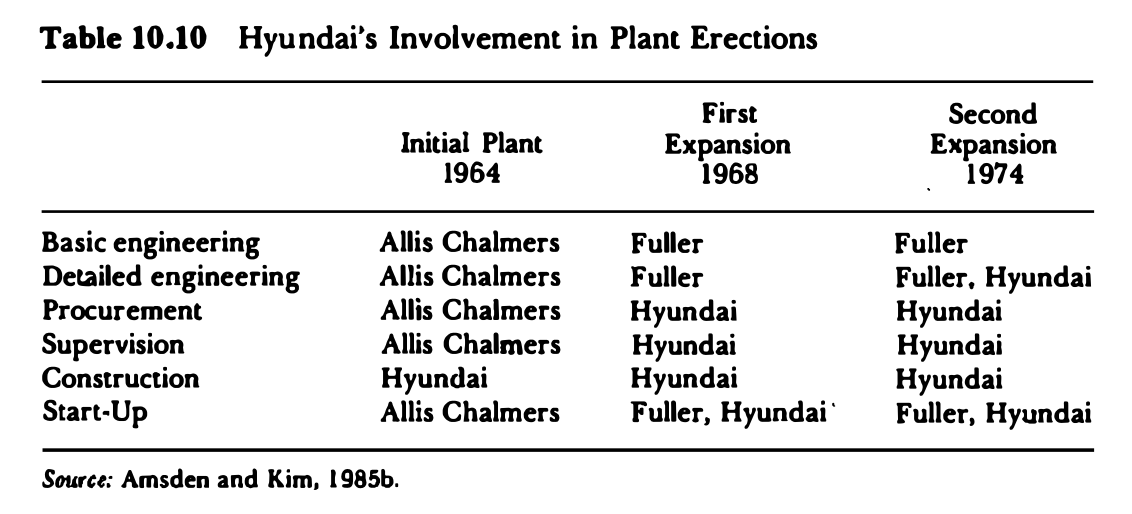

The Hyundai group, though its cement venture was not its largest, treated the project as a critical laboratory for technological learning. As Amsden details, for its first plant in 1964, Hyundai relied entirely on the American firm Allis Chalmers for basic engineering, detailed engineering, procurement, and supervision, undertaking only the construction itself. Crucially, however, the company consciously “unpackaged” the technology transfer. Within a decade, as illustrated in the table below, Hyundai had taken over every aspect of project execution except for basic engineering - the domain of specialised process experts. It was this cultivated mastery, not merely the capacity to produce cement, that provided the foundation for Hyundai’s future. The cement plant became a training ground for managers who later applied their skills in quality control, process engineering, and inventory management to launch Hyundai Motors, which would two decades later become a global automotive exporter.

Amsden writes:

The assimilation of cement-making technology was the basis for Hyundai's successful bid, ten years later, on a turnkey cement plant export to Saudi Arabia worth as much as $208 million. As for manufacturing capability, Hyundai used its cement plant as a laboratory to train its managers with backgrounds in construction, before as signing them to other manufacturing affiliates. Trainees gained experience in inventory management, quality and process control, capacity planning, and so on, thus spreading basic production skills throughout the Hyundai organization. After Hyundai Cement, the next manufacturing affiliate in the group was founded in 1967 and named Hyundai Motors. Twenty years later it became the first independent auto maker from a late-industrializing country to export globally. The first president of Hyundai Motors was a former president of Hyundai Cement.

This demonstrates that the true benchmark of success is not the origin of the initial technology, but the ferocious intensity of the effort to absorb and master it. The Hyundai model shows that true assimilation turns a domestic project into an exportable capability. Nigeria’s approach is a contrast. Even as its champion - Dangote Cement - expands abroad, it does not export hard-won Nigerian expertise because none has been cultivated; instead, it simply calls Sinoma to build for it in Senegal or Zambia, exactly as it does at home. The argument, therefore, is not against initial dependence - a necessary starting point for any latecomer - but against the conscious choice to remain in a state of technological backwardness. The first and non-negotiable requirement of any serious industrial policy must be the demonstrated, incremental mastery of the underlying technology- a process that produces a diaspora of skilled engineers and managers, not just billionaires and tonnes of output. What Nigeria has chosen to do is outsource the very learning that defines genuine industrial power, prioritising the counting of fortunes over the cultivation of knowledge.

In contemporary India, a typical announcement for a new cement plant or expansion will meticulously delineate the roles between foreign technology providers and local firms. Contracts are structured to ensure a transfer of responsibility, with Indian companies openly celebrating their growing in-house engineering capabilities and research & development milestones. Major players like UltraTech Cement publicly detail partnerships where they leverage foreign expertise for specific equipment while emphasising their own project management and execution roles. Furthermore, annual reports from firms like Ambuja Cements dedicate entire sections to ‘Intellectual Capital’, explicitly touting home-grown innovations in process efficiency, alternative fuels, and product development, even as they continue to utilise aspects of the global technology stack.

In Nigeria, one struggles to find any similar discourse on proprietary process innovation, home-grown engineering feats, or the cultivation of intellectual capital. The output of the Nigerian cement barons is measured in billions of dollars of profit and millions of tonnes of a basic commodity, not in patents, process patents, or a demonstrable mastery of the complex science they have paid others to install. The ambition appears to stop at the factory gate. Perhaps more worryingly, they seem to have decided that the surest path to perpetuating wealth is to simply mimic each other and settle into a cosy oligopoly. In this arrangement, the threat of foreign competition - the very force that might compel technological ambition - is safely held at bay by government policy, allowing them to profit from a captive market without ever being forced to truly master their craft.

Defensive Capacity

An equally insidious dynamic is unfolding beneath the surface of Nigeria’s cement industry: the construction of defensive capacity. While the nation is told that new plants represent growth and progress, the reality is that incumbent players are engaged in a strategic land grab to entrench their dominance and lock out future competition. They are aggressively cornering the country’s finite limestone deposits and building excess production lines in key regions to make market entry prohibitively expensive for any potential newcomer.

The most damning evidence of this strategy is the underutilisation of existing capacity. Industry data suggests Nigerian cement makers are currently using only about 50% of the production capacity they have already installed. Yet, expansion continues apace. This is not the behaviour of firms in a competitive market racing to meet consumer demand but a tactic of an oligopoly building moats. By sitting on massive deposits and operating well below potential, they artificially constrain supply, keep prices high, and protect their margins, all while the regulator and government remain fast asleep at the wheel. Any meaningful action to break this cycle - such as splitting licences or forcing divestments - would require a monumental amount of political will that has so far been entirely absent.

To reinforce the point, this strategy of defensive entrenchment is actively facilitated by a permissive regulatory environment. A 2016 World Bank report, Breaking Down Barriers: Unlocking Africa’s Potential through Vigorous Competition Policy (PDF, page 54), directly highlighted this issue, noting that in Nigeria, "Dangote holds the Mining Lease Agreement (MLA) for the limestone quarry feeding Sub-Saharan Africa’s largest plant, the Obajana plant," and that the total reserves covered by its licences "is proposed to last for more than 90 years." The report dryly observed that this is "longer than the cement plant’s expected life of 50 years and would indicate that there may be some room to either award a license to more than one firm in the area."

This is the anatomy of a captured market: incumbents are gifted control over finite national resources for generations, ensuring that the barriers to entry remain insurmountably high while the government, in effect, looks the other way.

Conclusion

The most recent book I read is Dan Wang's Breakneck: China's Quest to Engineer the Future. Its third chapter contains a meditation on 'process knowledge' - a concept that has stayed with me and feels painfully relevant to Nigeria's predicament. Wang distinguishes between technology as mere tools or blueprints, and technology as the deeply ingrained, practical proficiency gained from experience - the kind of knowledge that exists in people's heads and the patterns of their relationships. It is this process knowledge, he argues, embodied in communities of practice like Shenzhen's manufacturing ecosystem, that forms the true bedrock of technological ascendancy.

This mastery has allowed China to deploy cement in ways the world has never seen. As Vaclav Smil has documented, the 4.4 billion tons of cement China produced in just the two years of 2018 and 2019 nearly equalled the 4.56 billion tons the United States made during the entire 20th century. This command of material and process has enabled the construction of entirely new cities like Xiongan (among many many others) - a $116 billion project rising from marshy farmland that represents what Chinese officials call a "one-thousand-year plan" in civilisation-building, complete with government complexes, data centres, and relocations of major state companies.

Nigeria's reality could not be more different. It is difficult to survey the country’s landscape and believe it is a nation that has produced multiple cement billionaires. Housing remains prohibitively expensive, and unfinished buildings blight every cityscape - because constructing a home has become a lifelong endeavour for many, due in large part to the crippling cost of cement. Structural collapses, caused by shoddy materials and cost-cutting, now occur with such grim regularity that they barely disturb the national consciousness. When floods inevitably come, the devastation is magnified because vast numbers of Nigerians still live in vulnerable mud housing (PDF, page 22) - a fact underscored by numerous reports. This has led to tragic, preventable loss of life, a cycle of disaster that repeats with horrifying frequency. It is a profound national irony that a country which has poured such immense resources into cement production remains so visibly underserved by it.

Cement policy was Nigeria's critical inflection point - no other industrial effort has received such fervent support through import bans, tax breaks, and the extraordinary prices paid by ordinary Nigerians. Yet in return for this monumental national effort, the country gained capacity without capability, production without proficiency. It outsourced innovation and process knowledge to Sinoma without requiring beneficiaries to absorb and domesticate that knowledge. The result is an industry that operates as a closed loop: Chinese engineers build, maintain, and operate the plants, while Nigerian owners collect rents.

This policy represented a once-in-a-generation chance to create a hub of engineering excellence, to cultivate process knowledge that could have diffused into other sectors, training generations of engineers and innovators. Instead, Nigeria created glorified middlemen who simply buy technology, apply hefty margins, and charge Nigerians for the privilege. The country has outsourced the very learning that defines genuine industrial power, prioritising the counting of fortunes over the cultivation of knowledge - and the empty buildings and crumbling infrastructure stand as permanent monuments to this failure.

It is time to ask hard questions of a policy that has taken so much from the Nigerian people and yielded so little in return beyond private fortunes. Why does a country with such immense potential tolerate an industrial model that prizes ownership over understanding, and profit over progress? Why does it celebrate the capacity to produce cement, but ignore the far more critical failure to cultivate the knowledge that makes production useful? The future of Nigeria will not be unlocked by tonnes of output, but by the process knowledge that it gains from learning how to do things.

Until Nigeria demands more than billionaires from its industrial policies, it will remain a nation of consumers, always paying for the innovation it has outsourced to someone else.

Dangote’s (and the Nigerian political establishment) behavior is actually not that different from that of their forefathers. The whites came and traded guns with West Africans as early as 1600s…. Two hundred years, there was absolutely no significant technology transfer, and those same guns — that African kings and princes had been trading for over a century — were used to subdue them. Even the Dane guns that were produced locally were made from salvaged parts of other imported guns. The superiority of European firepower stared them in the face for over two hundred years, and instead of rapidly adapting to it, they decided to use it to pursue their own narrow goals. As they say, many such cases.

I must concede to this man's extraordinary fecundity in churning out thought-provoking material, on a regular basis.

It is so good that I am re-reading it for the fourth time.

The problem with the educated class is that they are caught up in the business of survival and paying scant attention to the extraordinarily extreme wealth transfer happening under their noses.

I was in Ibadan for the entirety of last week and I was profoundly depressed by the level of human capital flight.