Capitalism In The Colonies: African Merchants in Lagos, 1851 - 1931 [Chapters 9 - 10]

Hot Cocoa

When we discussed Chapter 5, we focused a lot on JPL Davies and how his fortunes rose and fell culminating in him being declared bankrupt in 1876. One of the effects of the bankruptcy was to severely limit his business options i.e. he could not set up a business under his own name for fear of his creditors coming after him. We have of course extensively discussed the merchants who exported produce from Lagos and imported all kinds of goods from abroad in exchange. JPL’s story - his second act to be specific - allows us move inland from Lagos to the source of all the produce that was being exported. In 1880 he bought land (he paid with rum and kola nuts) in Ijon for the specific purpose of engaging in agriculture. This was effectively an ungoverned space in the middle of nowhere bordered by the Egba, the Ijebu, the Dahomeans and Lagos.

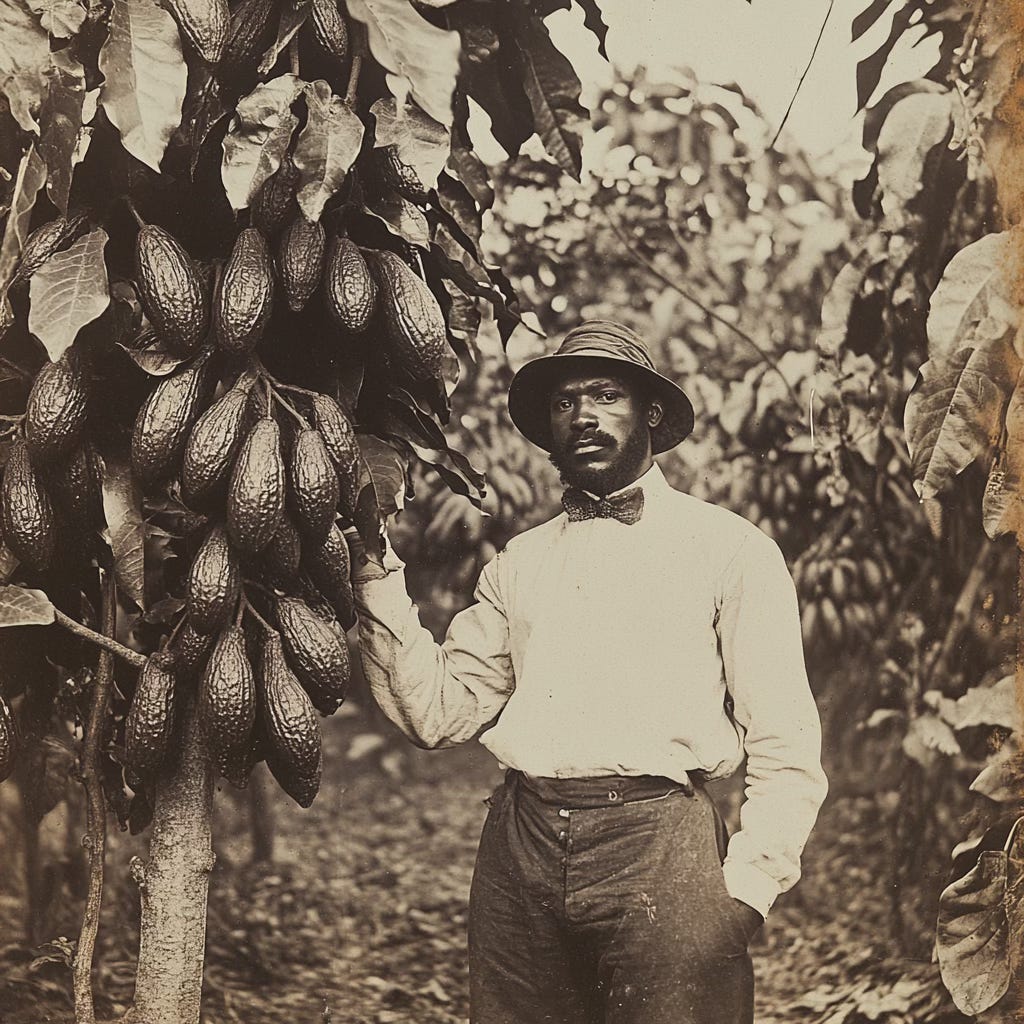

The farm - named Woodland Estate - began with a number of experiments. He planted yams, coffee, kola and of course cocoa (by this time, palm oil and kernels were played out as hot commodities). In the event, cocoa proved to be the biggest hit and a decade later in 1890, a colonial official who toured the farms in the area noted ‘a very encouraging example of enterprise and energy’ on JPL’s farm which had ‘1,500 full bearing cocoa trees that were eight years old and 5,000 young plants’. He went on to say he also noticed kola and coffee but that they were ‘less satisfactory’, confirming cocoa as the hit crop. It’s not clear where or how JPL obtained the expertise to start a large plantation but the same colonial official visited the farm three years later and described the novelty of such an undertaking in the colony with 10,000 cocoa trees planted over 300 acres. By 1895, the colonial Botanic Station that was set up to distribute new seeds and crops to farmers for planting across the colony was itself being supplied by JPL’s farm.

One highlight of this chapter is the inclusion of a newly discovered diary kept by JPL that documented his farm life from 1896 to 1899. It is a fascinating, if depressing and all too familiar, story of the issues he faced running the farm. Workers were often unreliable and would refuse to work. Anytime he traveled to Lagos and came back, he would discover things had been stolen on the farm. A lot of his time was spent resolving petty issues between staff and locals including one time when ‘Akande, the husband of Ramatu, lodged a complaint against the head farm labourer, Oje, for using indecent language against his wife.’ There was insecurity too which forced him to hire boys to guard his farm from invaders. He on occasion also lamented lack of rain which damaged hundreds of cocoa trees and showed up in the recorded export numbers for Lagos as a whole - for instance 21 tons of cocoa in total were exported in 1895 which then dropped to 12 tons in 1896.

But JPL, a shrewd man, also pinpointed what he thought was the cause of labour being so expensive and unreliable - the end of internal slavery. In his reckoning, colonial rule had seriously disrupted the large plantations which produced palm using slave labour. Once the slaves were free, they deserted the plantations which suddenly found themselves bidding for paid labour. Workers now had a choice and could simply refuse to work if they didn’t want to. Interestingly, he also pointed to the role of the stigma that had been associated with slave labour on farms as another reason why many were no longer keen on doing it. Labourers could instead plant on a small scale for themselves rather than taking up employment on a large plantation that reminded them of the horrors of years gone by. He tried all sorts to mitigate the issue including developing machines to reduce labour usage and in 1898 he said he ‘tried two women and found them better than the men in breaking and curing the pods’.

A man who grew rich in the first act of his life by being the face of the colonial civilising mission in Nigeria - and took those values deeply to heart - then lost everything by making bad financial decisions. If that had been the end of his story, it would not have been unique or strange. What was unique was the way he came back for a second act and became a pioneer in farming outside of Lagos. He spread crops as he spread ideas and Nigeria has much to be thankful to him for. His struggles at the time with paid labour (he held on to his value of always paying for his labour and never ever using slaves) and general cultural issues that continue to affect any kind of enterprise in Nigeria today are worthy of reflection.

The past was not a different country.

- Feyi

From Port to Capital

1892 marked a significant turning in the history of Lagos. The British colonial government adopted a military solution to trade disruption to the port caused by the warring surrounding Yoruba states. The invasion of the Yoruba hinterlands began a colonial expansion that had a transformative effect on Lagos and the merchant class. The tenth chapter discussed the implications and ramifications of this significant shift in colonial governance that culminated in the creation of what was then known as the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria in 1914.

After the invasion of the Yoruba hinterlands, the colonial policy changes, including the amalgamation of Lagos with Southern Nigeria, were initially intended to improve administrative efficiency. However, the policies prioritized British economic interests, especially establishing trade routes and infrastructure, which benefited British firms over local African businesses. The economic governance imperative was creating an internal free trade market with the port of Lagos as the trade hub that connects the domestic economy to the rest of the world. This overarching imperative by the British was implemented to subjugate the interests and autonomy of the local political and merchant class and subordinate them to British interests.

One of the things that demonstrated the importance of Lagos as a trade hub was the ambitious infrastructure investment by the colonial government to facilitate trade - especially the development of the Lagos railway and the improvement of the port. The railway was constructed to connect Lagos with the broader Nigerian hinterland, effectively expanding trade access and streamlining the export of palm products, especially palm kernels. Despite its strategic benefits, this infrastructure required substantial investment, and the colonial administration covered these costs through loans raised on the London stock market, amounting to over £8 million by 1911. The port harbour facilities were also developed. Initially hindered by a sandbar that prevented large steamships from docking directly, the harbour underwent extensive upgrades beginning with dredging operations in 1906. In 1908, breakwaters were constructed, and further expansion continued with the Apapa harbour development across from Lagos. This harbour project enabled larger vessels to access Lagos, fostering trade growth but accumulating significant long-term costs.

Advancements in transport, port and communication infrastructure (like the installation of a submarine cable) firmly established Lagos as the economic centre of the expanding colony because the infrastructure investments were part of a broader strategy to maximise the utility of Lagos as a trade hub. Other institutional changes like the monetisation of the economy through the introduction of silver currency, and the establishment of the Bank of British West Africa (BBWA) further solidified the model of an entrepôt economy. This made sense for the British because the colonial government was solely dependent on the taxation of trade to finance itself.

The cumulative effects of these changes had significant implications for Lagos' economic environment. The influx of expatriate firms created an environment that Hopkins called 'compulsory globalisation', intensifying the presence and power of British businesses. Although the colonial economy fostered trade growth, it simultaneously restricted African entrepreneurial opportunities through racial discrimination and policy biases. Lagos, however, experienced infrastructural growth, becoming a strategic capital with improved harbour facilities and a large port connecting a vast hinterland. Nonetheless, the economic benefits for African merchants were limited as structural inequalities deepened.

This chapter was the most sombre reading for me in this excellent book. It typifies the complexity of interpreting history and the sad reality of living with some of its adverse effects. There are two big implications of the events of this chapter. Firstly, the colonial expansion established internal free trade but also destroyed many independent states' fiscal capacity. The colonial government depended on customs duties, which surged as the infrastructure for trade was upgraded and internal trade barriers were removed. Many hinterland states relied on tolls from trade routes and lost their sources of revenue to colonial domination. This effectively meant they were deprived of resources to resist unwanted colonial policies.

Furthermore, despite the centralisation of fiscal policy by the British, a centralised fiscal state that could collect revenue across the protectorates did not emerge. Government revenue remained dependent on customs duties. The lasting legacy here was that future trade policies became solely about expropriating trade rather than facilitating trade for growth. The absence of a centralised fiscal state and capacity would also ensure no new investment in trade infrastructure, even as old ones deteriorated.

The second significant implication from the events of this chapter involves the fate of the local merchant class, unlike the early institutional innovations that created new legitimate commerce and enabled them to create wealth and an economy. The new institutions and rules were explicitly for the advancement of colonial objectives. The infrastructure improvements brought them mixed fortunes. They gained access to larger international markets but faced fierce competition from British firms, who were better resourced and benefited from preferential policies. Due to the deep penetration of European firms into Nigeria's hinterland, the colonial economy fostered dependency. African merchants became reliant on British banking, shipping, and monetary systems, reinforcing an economic hierarchy that disadvantaged local entrepreneurs. This dependency limited the ability of African merchants to exercise autonomy within their markets, perpetuating a cycle of economic subordination.

This decline of the domestic merchant class swung the balance of power of the future state that emerged in favour of the government. Unsurprisingly, the consensus of the business elites became that of state capture. Lagos did not only become a bustling hub of trade and commerce; it also became the dealroom of political power.

- Tobi

Awesome 👌

Thank you, Feyi and Tobi, for your review on such an historical document.

It allows us to see that there is nothing we see now, that was not before. Maybe reinforcing the believe, that, life, is a stage, we come play our part , leave and the story/drama continues.

Thank you, very insightful

Adenrele Adeniran