Capitalism In The Colonies: African Merchants in Lagos, 1851 - 1931 [Chapters 5 - 6]

"History is what we know now rather than what was happening at the time"

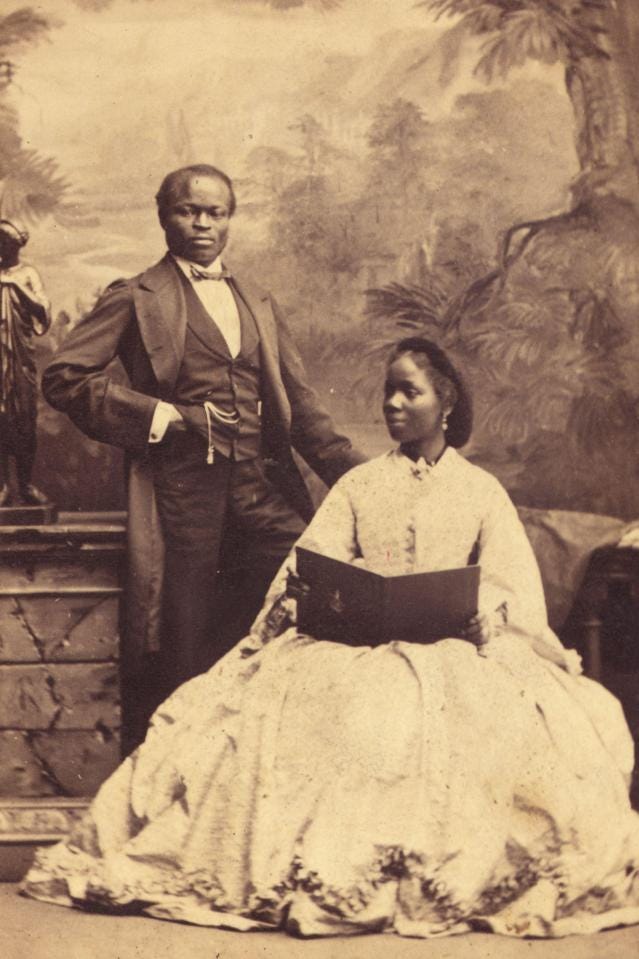

A Victorian Gentleman

The life of James Pinson Labulo (JPL) Davies stands in sharp contrast to that of Daniel Conrad Taiwo, also known as Taiwo Olowo, whom we encountered in the previous chapter. Taiwo was illiterate—though he freely used lawyers when it suited him—and untroubled by the immorality of slavery, even enslaving people who owed him money. JPL, however, took pride in his stance against slavery; in 1861, he documented a list of his 133 employees, noting that ‘not one of them was a slave’. Unlike Oshodi Tapa and Taiwo Olowo, who moved from slavery into legitimate commerce, JPL built his business entirely on free labor. Another key difference lay in their origins: JPL was of Egba descent, while Taiwo was Awori. When Colonial Governor Glover began his anti-Egba policies, JPL and Taiwo found themselves on opposite sides of the divide, with Taiwo eagerly supporting the governor for business advantage. Despite their differences, the two men were both openly Christian and shared membership in a secret society called the Oparun.

I've long considered myself a devoted admirer of JPL Davies. Eight years ago, I wrote an article in The Guardian celebrating his pioneering role in introducing cocoa to Nigeria and West Africa. Yet, Chapter 5 of this book brought fresh insights into his life, especially around the mysterious origins of his considerable fortune (its size is indisputable, but details on how he amassed it remain elusive). Both JPL and his brother Samuel joined the Royal Navy as part of an initiative led by Henry Venn, the prolific Victorian reformer of the Church Missionary Society (CMS), who was endlessly inventive in his mission to build a new elite in Nigeria. (Remarkably, despite his immense influence on colonial Nigeria, Venn never once visited the country as far as I can tell). Through his program, JPL and Samuel joined the West Africa Anti-Slavery Squadron aboard HMS Volcano, where they were trained in navigation and seamanship, becoming the first West Africans to receive such training.

In 1852, a year after joining the Royal Navy, JPL and his brother Samuel left to captain merchant ships across West Africa. But when one of those ships sank in a storm in 1855, JPL decided seafaring was too risky and shifted to business on terra firma—a wise choice, as his brother, who remained at sea, tragically drowned in 1857. JPL leveraged his maritime knowledge and connections to launch his own ventures and quickly amassed a fortune. From here, however, the details of his business dealings become scarce. As Professor Hopkins writes:

Unfortunately, little more is known of Davies’s commercial activities at this time, even though it was during the first decade or so of his business career that he became very wealthy and made his largest philanthropic contributions.

JPL dabbled in cotton trading, but there’s little evidence to suggest it was profitable enough to account for his rapid accumulation of wealth. Perhaps his years as a captain for merchant ships earned him significant capital before he transitioned to business. Whatever the source, his philanthropy was remarkable for the era. He actively supported the founding of the CMS Grammar School in 1859 and its expansion a decade later, built a library in 1872, and donated generously to several churches in Lagos.

The second revelation was just how much of a rise-and-fall story JPL’s life became. The details remain somewhat murky, but the broad strokes are clear. In 1872, he mortgaged all his West African properties (15 in Lagos alone) to a Manchester firm, Child, Mills & Co., for a £60,000 advance. Unable to repay, he was declared bankrupt in 1876, sparking a grueling 15-year legal battle to recover as many of his properties as possible. Although he regained a few, he lost most. The start of his troubles came when Child, Mills & Co. went bankrupt shortly after advancing JPL the funds, and its creditors immediately began pursuing JPL. It was then revealed that some properties he had mortgaged were actually family-owned and not his to collateralize, sparing them from seizure but severely damaging JPL's reputation as a Victorian gentleman. As the British judge in the case brought by his creditors in 1880 said:

This is a matter that will bring discredit and shame upon men who had hitherto borne and honourable name

JPL’s creditors managed to have his trial moved to Accra after the Lagos court conceded that finding a jury willing to convict him locally would be nearly impossible, regardless of the evidence because his philanthropy had won him deep-rooted goodwill across Lagos society. Ultimately, he narrowly avoided conviction and prison when his creditors overplayed their hand, misjudging the extent of his influence and support.

A key factor in JPL’s financial troubles lay in the complex application of the English Bankruptcy Act of 1869 to Lagos, which was then a British colony. Although he had been declared bankrupt in Manchester, Lagos was not yet under the Act, so any English creditor seeking to claim a debtor’s assets in Lagos had to navigate the Lagos courts. This changed only in 1876, when the Lagos Supreme Court was established—and later in 1877, authorized to act on behalf of the Manchester court—finally allowing foreign creditors legal means to pursue debts locally. The lack of bankruptcy protection also meant JPL himself couldn’t file under the Act to shield his assets and future earnings. Moreover, Lagos had yet to implement company registration, so the concept of limited liability was absent, adding to his personal financial vulnerability.

Here’s how Professor Hopkins describes the aftermath of all of that:

The Privy Council’s ruling in 1891 that the English Bankruptcy Act did apply, after all, to Lagos, prompted considerable discussion in the town and led some commentators to call for an Insolvency Act for Lagos modelled on the English Bankruptcy Act of 1883. At present, the argument went, debtors were at the mercy of creditors. English firms were protected; African merchants were hounded and could not even use business losses to mitigate their position. The issue was still being discussed in 1912 with reference to Child, Mills, CSM and Davies. Davies’s career was characterised by innovation. Even in defeat, he contributed, however unwillingly, to the clarification of corporate law in ways that legal experts have yet to recognise. (Page 157)

By 1884, JPL was finally discharged from his bankruptcy, but the toll on his reputation and dignity was profound. This was a man who had once moved in elite circles, personally acquainted with Queen Victoria herself. His 1862 wedding to Sarah Forbes Bonetta —Victoria’s goddaughter—had drawn such public attention in Brighton that police had been required for crowd control. The fall from such esteemed social heights to financial ruin and public scandal was nothing short of humiliating.

In 1880, amidst JPL’s ongoing legal battles, Sarah passed away, likely from the strain that had engulfed the family. His daughters relocated to England, possibly seeking refuge from the humiliation shadowing their family, and ultimately adopted a British life. His son joined them initially but tragically passed away on a return trip to Lagos in 1877. The family’s scattering and losses underscored the far-reaching toll of JPL’s financial and legal troubles.

This story has echoes that once again resonate with modern Nigeria. The camaraderie of the elite, enduring through political divides—like Taiwo and JPL’s 40-year friendship despite opposing views on the Colonial government’s Egba policy. The abrupt emergence of unaccounted wealth, easing its way into all layers of society. And the image of a wealthy man, presumed shrewd, only to be dramatically undone by basic missteps—in JPL's case, the lack of due diligence on Child, Mills & Co. before risking his entire fortune and inviting ruin on himself. And then there’s the perennial question of land ownership. Even now, Nigeria grapples with the same blurred lines between personal and family property, lacking the legal framework to settle these disputes definitively, just as in the 19th century.

JPL eventually got back into business and resumed his philanthropy. But he was never quite as wealthy as he had once been. His story is not finished and Professor Hopkins promises more to come in subsequent chapters.

- Feyi

Familiar Problems

The sixth chapter started with the second shock (see first review for the three shocks) that hit Lagos in Hopkins' narrative. Within two decades (1880 - 1900), the commercial fortunes of Lagos dwindled and brought economic decline to the domestic merchant class and anxiety to their European trading partners. This change in fortune led to political changes that would ultimately culminate in the invasion and subjugation of the Yoruba hinterland - cementing British colonial governance in the region.

The economic landscape of Lagos began to change in the 1880s, leading to a crisis for African merchants. Increased competition from British traders, worsened terms of trade, and colonial interventions chipped away at the profitable business environment that African intermediaries had enjoyed in previous decades. As British companies gained dominance in palm oil, cotton, and other exports, African merchants became sidelined. Global changes in commodity prices and fluctuating demands affected the local economy. British merchants benefitted from favourable trade terms and better access to capital, sometimes to the detriment of African traders. However, as Hopkins himself noted, the struggles of the Lagos economy were caused by the new legitimate commerce not achieving any significant economy of scale:

A closer look at the main exports from Lagos during the period leading to the occupation of the hinterland in 1892 reveals that the volume of palm oil exports continued to increase during the 1880s from an average of 4,595 tons in the three years from 1880 to 1882 to an average of 8,136 tons in 1888–1890. The volume of palm kernel exports also rose, though more slowly, from 26,341 tons to 38,567 tons during the same two periods. What is striking, however, is that the average value of palm oil exports fell from £166,723 to £149,249 during the two periods, whereas the value of kernel exports increased from an annual average of £276,322 to reach £291,382. Lagos reflects the general direction of palm oil prices in London and Liverpool, which were also on a downward trend from the early 1850s and touched their lowest points in the nineteenth century between the mid-1880s and mid-1890s.3 Palm-oil producers and the predominantly British merchants and their African associates were earning less for supplying more. German merchants and the African merchants connected to them who traded in palm kernels were more fortunate: they were exporting more and earning more.

These trends are reflected in the terms of trade for the period, which have now been computed specifically for Lagos and include data on palm kernels, the leading export, for the first time (see figure 2.2). The net barter terms of trade for palm oil reached a peak in the early 1880s and then fell until the close of the century. Palm kernels, however, performed differently, declining in the 1880s, but beginning to rise at the close of the decade and continuing until 1907. As in the period 1856–1880, the broken lines in figure 2.2 indicate sharp variations within these general trends that identify the uncertainties facing decision-makers at the time.

As noted earlier, Lagos merchants were price-takers rather than price-makers. Palm produce entered the international oils and fats market, in which it competed with substitutes as well as with identical produce from other sources. The market price was determined both by specific industries that used palm produce in the manufacturing process and by broader demands that reflected the state of the national economy. Needless to say, neither of these determinants took account of the interests of merchants in Lagos. Consequently, estimates of the demand for Lagos produce, which occupied a minute place in the international market, were as hazardous as they were complex. Unpredictability flourished on the supply side as well. The quantity of palm produce available was partly a function of rainfall, which could vary markedly from season to season. In the absence of quality controls, produce could be adulterated or poorly processed. These circumstances not only affected the price produce could command but also made forward contracts difficult and a futures market impossible. Political priorities among the hinterland states were an additional consideration that continued to influence the volume of produce available for sale. Local prices were highly sensitive to all these considerations and fluctuated, sometimes markedly, not only from season to season but also from day to day.

The struggles of Lagos's economy also altered the incentives of British colonial governance. British expansion into Yorubaland marked a turning point for Lagos’s economic and political future. Initially, British policy aimed to avoid further territorial acquisitions, but a mix of local and global forces increased the economic pressures that changed the mood and temperament in London.

First was the perpetual conflict in the Yoruba states in the hinterland, which was disruptive to trade in Lagos:

Relations with the hinterland states were a nagging problem that had preoccupied colonial officials from the time of the consulate onwards. Yorubaland was in a fluid and unstable condition as a result of the collapse earlier in the century of the Oyo Empire to the north and the irregular but continuing incursions from Dahomey in the west. New states and statelets were being created; citizens were being formed out of a mobile population that contained many immigrants, refugees, and slaves; boundaries were established, disputed, and redrawn. The state of the country mattered because it supplied the palm oil and kernels that were the basis of the export trade from Lagos and consumed most of the manufactured goods imported in return. By mid-century, Ibadan had emerged as the predominant power with an ambition to control the whole of Yoruba country.64 In reaction, states to the east, such as Ekiti, Ijesha, and Ife, and those to the south, such as Egba and Ijebu, responded by defending their independence. The conflict was discontinuous, but it was renewed in 1877 and ran on, with pauses, throughout the 1880s.

The theme explored by Hopkins in this section is the tension in the abolition of the slave trade and realising the full economic gains of the new commerce - leading to a crisis of adaptation, a theme much advanced by the historian Robin Law:

Palm oil was not as profitable as slave-trading; adaptation by producing and trading oil by means of slave labour did not shield slave-producers from the adverse terms of trade that characterised the 1880s; hostilities among Yoruba states were exacerbated by efforts made by traders and producers to use state agencies to shift the burden of falling profits to shoulders other than their own. The ultimate conflict was between the continued dominance of Yoruba military interests and the development of the full potential of ‘legitimate’ commerce.

The military response to the crisis brought by the end of the external slave trade was clearly incompatible with the needs of the new international economy. Adaptation through intensified slave-raiding interrupted production and trade, created insecurity, and brought devastation to unlucky communities. Moreover, the absence of economies of scale in the production of oil and kernels at this time obliged large-scale producers to rely on compulsory labour, which was acquired through costly wars. These non-market, military supports were removed when peace descended. That large producers existed is beyond dispute; evidence of their importance, however, is currently beyond reach. Reports of small-scale production, using free and slave labour, are widespread but equally hard to quantify. A careful contemporary estimate suggested that 15 million palm trees were needed to produce the volume of palm oil shipped from Lagos in 1891. All that can be said about the division of shares at present is that the size of the export trade left plenty of room for both large and small suppliers. The new economy was struggling to emerge before the expansion of British rule into what became Nigeria but required fundamental institutional change for its potential to be realised. In the end, as Law concludes, the crisis of adaptation was posed and ultimately settled by the increasing pressure Britain exerted to resolve problems of integration that had exceeded the scope of informal influence.

The colonial government in Lagos's main concern was that the conflicts had disrupted trade at the port, which was bad news for government revenue and merchants' incomes. Multiple peace negotiations in the 1880s failed to appease the warring states. Hostilities were constantly renewed, leading to the closure of markets and trade routes - which always caused disputes between the traders in Lagos and those in the hinterlands, sometimes over prices, accusations of impurity, and even requests that escaped slaves be returned to servitude.

Rising commercial tensions were not helped by the growing French presence on the western fringes of the colony, creating a perceived or actual threat to Britain's interests. France's annexation of Porto Novo in 1883 raised concerns that further inland expansion could isolate Lagos, turning it into a port without access to a valuable hinterland. This encroachment would also constrict the colony's borders, risking reduced customs revenues crucial to maintaining the colonial government's financial stability. In 1892, the British resolved the matter with guns by invading the Ijebu state, which they concluded (along with Egba) to be the primary source of domestic troubles. This symbolised the expansion of British colonial rule in Yorubaland.

The military campaign to pacify the hinterlands opened new commercial routes but destabilized local economies. As British forces took control, African merchants, who had once operated with relative autonomy, now had to navigate colonial regulations and restrictions that limited their entrepreneurial freedom. This loss of status was keenly felt by the merchant elite of Lagos, including figures like JPL Davies. The shift from informal economic dominance to direct colonial rule meant that African merchants, who had thrived on their intermediary role, faced declining fortunes as their influence over trade waned.

The expansion of British control brought structural changes that affected Lagos' economy. The British introduced new governance and legal frameworks favouring European traders and restricting African businesses. Infrastructure projects, such as railroads and improved port facilities, were developed primarily for British economic interests, leaving African merchants to bear the brunt of increased competition without the resources or backing British companies enjoyed.

The sixth chapter is my favourite of the book so far. Without leaning too heavily on the significance of history, one can connect many dots about the nature of the post-colonial state that emerged. An economy that thrives solely on the export of a primary commodity but never manages to raise investment and output levels significantly and is severely prone to the international price movement of the commodity. The lack of technology adoption and the inability to achieve economic diversification from dependence on the export of primary commodities. A polity plagued by perpetual strife and desires to pull in a thousand different directions rather than leverage the strength of constructed integration. An elite class that is content with being intermediaries and only acts to protect the narrow interest of their rents. Do any of these sound familiar?

You tell me.

- Tobi

My oh my.