10% Less Mediocrity

Food Security edition

In today's edition of this running theme, I am returning once again to a subject I have written most about on this blog - food. You are possibly tired of me writing about it, but you are going to have to bear with me. Earlier in the week, I read a truly excellent essay by economist Karthik Tadepalli on how Brazil transformed its agricultural sector to become a true food giant. Here is Karthik:

In 1960, Brazil was poor, with a GDP per capita roughly equal to Nigeria’s today. Despite being an agrarian economy, Brazil was actually a major food importer and even a recipient of US food aid.

But today, Brazil is the world’s biggest agricultural exporter. While the country has not reached high-income status – its growth has been slow in manufacturing and services – its agricultural productivity growth has been extraordinary. Brazil is now the world’s largest exporter of soybeans, coffee, sugar, orange juice, and beef, and a leading player in corn, cotton, and pork. This transformation has occurred primarily through yield growth, rather than through expanding farmland. Brazil has quadrupled yields across leading crops since 1960 – faster than the United States, despite the US’s much higher agricultural R&D spending.

Here is a little background

Eliseu Alves discovered his unwelcome nomination to government on the radio.

It was 1972, and Alves was ready to leave Brazil. He had returned to his home country after finishing his PhD in agricultural economics in the US for what was meant to be a short stay – he had lined up a professorship at Purdue University. Along with a working group of Brazilian agricultural researchers, Alves proposed that the Brazilian government establish a new agricultural research corporation, Embrapa, that would focus on problems specific to the country and equip farmers with the knowledge and technology to transform Brazil’s stagnant agricultural sector. The government accepted the proposal and asked Alves to be Embrapa’s second-in-command. He declined. It was a rude shock, then, to hear his nomination to Embrapa announced on the radio only days later.

When Alves returned to Brasilia, the military government informed him that he could resign from his appointment, but then he would never work in Brazil again. Reluctantly, Alves accepted the position, intending to leave quietly after a couple of years. Instead, he stayed for twelve years, guiding Embrapa through its first decade and overseeing its transformation of Brazil’s agriculture.

So how did Brazil manage to pull off its amazing agricultural miracle?

A working group of agricultural researchers, led by sociologist Jose Pastore and Alves, identified a lack of applicable knowledge as the problem. Rural extension was based on the knowledge taught by American agronomists: knowledge cultivated in Iowa and Wisconsin, not in Mato Grosso or the Cerrado. That temperate advice withered in the tropical heat, and extension agents didn’t know how to answer farmers’ questions.

The working group concluded that they needed to create new, Brazil-specific knowledge for farmers. Thus, they created the blueprint for a new organization: a state-owned company that would conduct agricultural research with a clear mission to solve Brazilian problems, respond to farmer demands rather than academic curiosity, and maintain its focus through centers organized by crops and biomes rather than scientific disciplines.

Embrapa’s first significant win came in the Cerrado. The Cerrado is a massive biome in western Brazil, three times the size of Texas, and almost all of it was available for farming. But farming was practically absent from the Cerrado, because its soil was too acidic and nutrient-poor for crops to grow, and its climate was hotter than Brazil’s subtropical south, where farming was widespread. To make the Cerrado arable, Embrapa started an agricultural liming campaign – treating the soil with limestone-derived chemicals to reduce soil acidity. They also developed a new soybean variety that was tolerant of the Cerrado’s harsh climate, unlocking new possibilities for growing soy, a profitable cash crop. Today, the Cerrado hosts 70% of Brazil’s beef cattle and 50% of Brazil’s soy production, both of which are key to Brazil’s agricultural exports. And Brazil’s center-west region, of which the Cerrado is the biggest biome, has become the largest area of Brazilian agriculture.

Four months ago, I was also alluding the Brazil's success in agriculture when I wrote that:

Simply importing machines and techniques will not close the technology gap. Recent research on what economists call the “Inappropriate Technology Hypothesis” offers some insights on the nature of the challenge. This hypothesis reveals that agricultural innovations are not universally beneficial but are tailored to the specific ecological conditions of the countries that develop them. When high-income countries create technologies for their pest threats and growing conditions, these innovations often fail to address the unique ecological challenges faced by farmers in places like Nigeria.

Karthik outlined three lessons that are important to learn from Brazil. But my main focus is on the first one - investing in human capital:

Suppose you’re in charge of a brand-new research institute in a poor country, with the intimidating goal of transforming the country’s agriculture. You are under intense pressure to generate results, your organization’s continued existence is not guaranteed, and you have a tiny base of researchers to draw on – in 1975, Embrapa had only 28 researchers with PhDs. What would be your first priority?

You might throw all your researchers and money at one problem, prioritizing one area for a major push. That strategy could pay off – with a small but brilliant team, you could conceivably make some progress, thus living to see another fiscal year. But your ambitions would be strangled by the reality of having too few researchers to actually do research. Embrapa’s mission was to create knowledge with clear economic relevance to Brazil, and producing knowledge is really hard, let alone directing that research effort towards a specific topic area. (Just ask your favorite graduate student!) Without investing in your researchers, in a few years, your institute’s research outputs would dry up. Politicians would come knocking, asking you five things you did in the past week. Cue the game over screen.

What you would probably not try to do is immediately start spending huge sums of money on sending your research staff to do advanced research degrees, before they do any actual research for you. But that is what Embrapa did. In its first ten years, Embrapa spent 20% of its budget paying for its staff to get advanced degrees in agricultural science, at universities in the US and Europe. By 1988, it had more than 1,000 researchers with PhDs, most trained abroad on Embrapa’s dime.

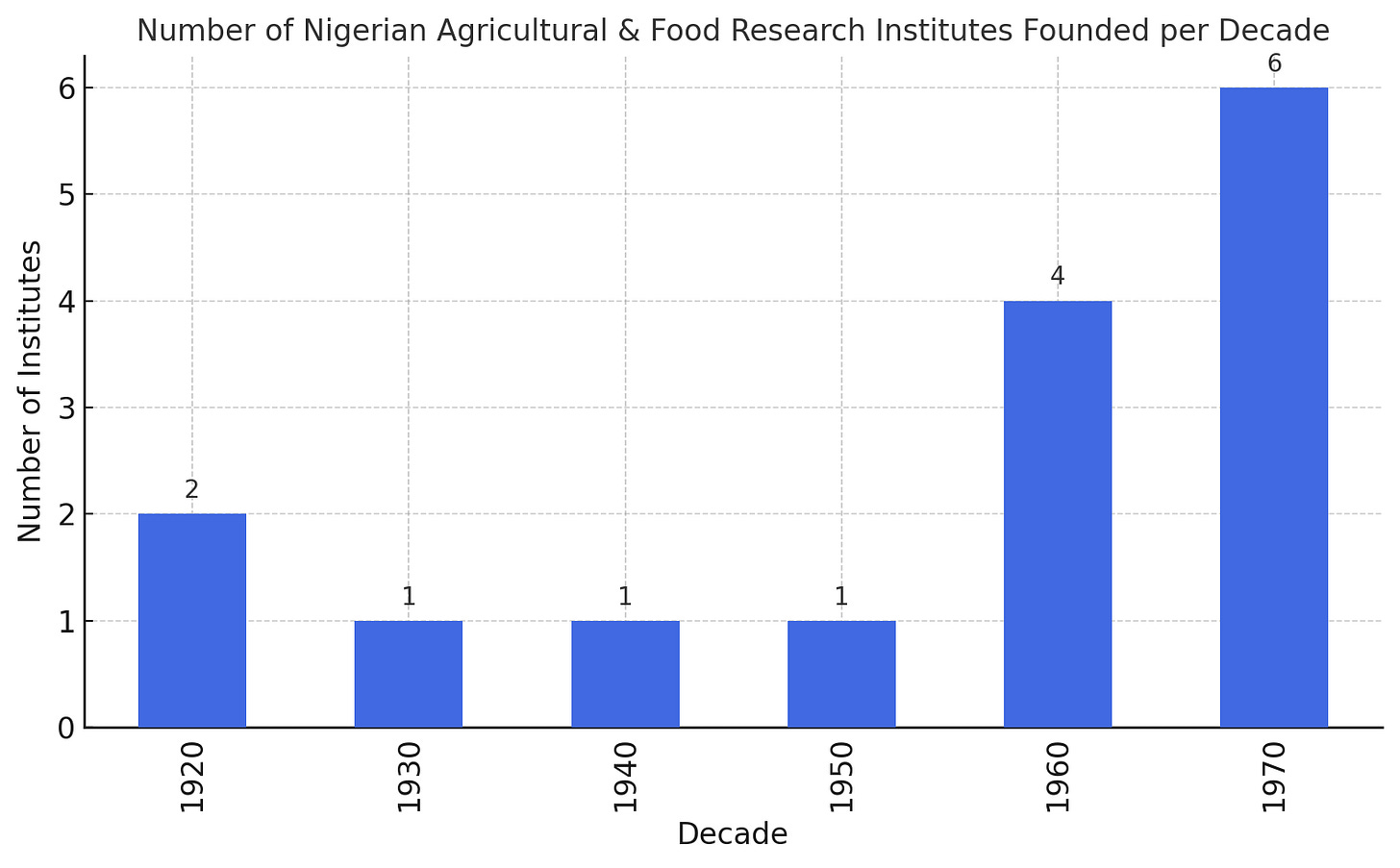

Nigeria has been struggling with the food problem for decades, and every successive government has always pledged a food security mandate. Usually, the mandate starts and stops with a ban on food imports. As Karthik pointed out, Brazil did everything in the development economics playbook. What made the difference was investing in human capital and adaptive solutions. Even more pertinently, Nigeria does not lack research institutes (see chart). So, imagine my utter lack of surprise when the oldest agricultural research institute in the country made a groundbreaking announcement. I will post the news article in full:

In its bid to ensure food security, the Institute for Agricultural Research (IAR), Ahmadu Bello University, ABU Zaria, has unveiled a new generation of high-yield, drought-tolerant and pest-resistant maize varieties to farmers.

The maize varieties were showcased to farmers during a Farmers’ Green Field Day in Bichi Local Government Area of Kano State.

Speaking during the event, a senior researcher with IAR, Prof. Ado Yusuf said the institute has a mandate to produce early generation seeds breeder and foundation seeds which private seed companies can multiply and distribute nationwide to ensure food security.

He said the field day was organized to demonstrate the benefits of the institute’s latest maize technology directly to farmers.

According to him, “Whenever we develop a new technology, we bring it to the field so farmers can see its advantages. Instead of keeping these varieties on our shelves, we extend them to farmers.

“There are over 200 seed companies in Nigeria. Once they collect these seeds from us and multiply them, farmers across the country should have no problem accessing certified seeds,” he said.

Addressing concerns about genetically modified (GM) crops, Yusuf clarified that Nigeria currently has only three approved and commercialized GM crops: Bt cotton, pot-borer-resistant cowpea (SampI 20T), and Tella maize (SAMMAZ 75T).

He stressed that Nigeria’s National Biosafety Management Agency ensures all GM crops meet rigorous global safety standards.

Similarly, the Principal investigator, Prof. Rabiu Adamu emphasized that the new maize hybrids could help Nigeria overcome food insecurity.

“This maize yields 7–8 tons per hectare and matures in 90 to 95 days. It is drought-tolerant and resistant to fall armyworm and stem borer, two of the most destructive maize pests.

“Farmers using the hybrid can save up to ₦70,000 per hectare on insecticides, while protecting their health and the environment,” Prof. Adamu noted.

A farmer in Bichi, Sunusi Dankawu expressed delight over the early-maturing, pest-resistant traits of the maize varieties.

He said, “these varieties clearly outperform our local maize. We faced no real challenges except the experimental planting pattern.”

Another farmer, Bashir Usman Boyi, said community members are eager to adopt the seeds:

“People come to see and appreciate the varieties. We only need to add some micronutrients, but the yield and quality are excellent,” he said.

These are not trivial claims. In what reads like a casual press briefing, the oldest agriculture research institute in the country is claiming to have solved the scientific, economic, and environmental problems of a very important crop. However, there was no research paper or information about one provided in this news story. Nobody at this newspaper found it worthy to ask follow-up questions, provide more context, or do a little bit more digging. For example, the new government has been in power for a little over two years, so when were the directive and the funding for this research issued? Has this solution been simply sitting on the shelf of the institute for a while, or is this new research? So many questions, but I doubt we will get any answers.

I will close with my favourite refrain on this subject. Agricultural transformation is not easy or simple. It is not just a case of being blessed with the land and the people. I want to plead with everyone with a public responsibility on this problem to at least act with a little less mediocrity.

Another wonderful write up. I have always gauged a writer by their ability to simplify technical concepts and by this measure, I would say you are a very talented writer.

This particular article in a way reinforces the comments I was going to make on the preceding article. I know we love to lambast our billionaires for what they are not doing but I think their actions/inactions are merely down to an understanding of how we as a people are are wired. We love to seek out the shortest route to an answer, sacrificing depth and thoroughness of thought and application. This is why we have a surfeit of internet scammers and yet have not really produced high end hackers/cybercriminals. Scamming is hard work but offers the possibility of quick returns without a need for deep technical knowledge. We only work hard in short bursts on things that offer us quick returns. We are not necessarily drawn to doing bad/immoral things but simply to doing what can offer quick returns be it legal or illegal. This usually leaves us with low quality answers/solutions. This is very evident in agriculture. A begging question remains how is it that as a people, we have been agrarian for centuries and still somehow have not organically innovated to improve yield?

I would blame the government for not providing research opportunities but having being raised right within the university community housing IAR, I can say with some certainty that the issue is not a lack of these institutes nor the development of their professional capacities but rather that their work usually ends up gathering dust on shelves or only getting implemented by small time farmers within easy reach of these institutes. While these research institutes have done significant work especially in developing improved seed varieties, there really has never been a progressive enough mindset among farmers to ask questions and then seek solutions leading them to these places/people nor any political will to push them to do so. Look for example at the saga of the Zimbabwean farmers brought in as some sort of political prop by a governor. But for curiosity and a desire to improve, what exactly set those farmers aside from our farmers who should have decades of institutionalized passed down knowledge on ag practices? Well the difference is one group asked pertinent questions to find answers to improve their end product and limit uncertainties, while the other ascribed these uncertainties to the whims of a supernatural being, and simply acquiesced to living with them from year to year. And when they left after their short stay, can we say anything changed in farming communities who worked directly with them? The answer to that is up in the air.

This underlies why the billionaires are the way they are. Their fastest route to success does not lie in developing local solutions but in trading in already available solutions. And if they pivot to investing in developing products and trade routes based on local produce, they would likely end up like the Dangote tomato factory - a shiny investment that cannot find tomatoes in sufficient quantities due to farmers not willing or unable to keep up with demand. This would probably have been the fate of the refinery as well but for the availability of international sources of crude oil.

Until there is a paradigm shift in mindset which would be difficult to see through because we have been the way we are for centuries, a society where innovation is eschewed for paying obeisance to the supernatural, progress will merely be limited to copying what others have perfected. Not because local solutions cannot or have not been produced but simply because not enough people are truly seeking to do the hard and in most cases thankless work of pioneering moving research into development and then into practicable solutions.

Interesting write up. Can you show a reference to the chart attached. Also as an active participant in the sector, I think the challenges are induced by political and to a very large extent socio-cultural constraints (which is typical of any sector in the country). We have the human resources but they are scarcely motivated to effect any real change.