One More Time for the People At The Back

The folly of protectionism. Agriculture needs adaptive solutions, not Trumponomics.

Okay, I know I said my most recent essay on agriculture will be my last word on the subject for a while, but I need to get some things off my chest and then let it rest a little bit. A few weeks ago, Mallam Nasir Elrufai—a former minister of the Federal Capital Territory and former governor of Kaduna State—made a media splash (as he is wont to do) with an interview on the Arise TV channel. The crux of the interview was about politics, mainly why he is unhappy with the president and the ruling party, which he helped found.

But his brief comments on economic policy are of immediate interest to me. The former governor remarked that some of the administration's economic reform policies are "orthodox policies" that he approves. It would have been nice for him to specify those orthodox policies, but the interviewer did not press him on it. He was also critical of the government's agriculture policies, noting that food prices might be easing, but this is to the detriment of farmers. Again, it would have been great for the former governor to explain his meaning in detail, but we can fill in the gaps. I believe what the former governor is implying is that food prices are dropping because of food imports, which is bad for local food production. There is nothing new here because this idea has become an article of faith among Nigeria's political elites. This idea is also wrong, and the policy response it inspires has always caused poverty.

There have been recent media reports that food prices are falling. This relief should be welcomed after years of rampaging food inflation and a cost-of-living crisis. But as Waziri Adio recently pointed out, no one knows why prices may be falling:

A number of media outlets have documented the notable fall in food prices in the last few weeks. I have seen stories and surveys in Daily Trust, BusinessDay, Nairametrics, ThisDay, The Guardian, TVC, Channels and Aljazeera, among others. I have also spoken to a few people in the food business. Prices of most raw food items that in and out season are falling while those of processed and packaged food items and fruits are not falling yet or, in some cases, are still rising. The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) publishes two important reports that should help with concrete data: the Cost of a Healthy Diet (COHD) report and Selected Food Prices Watch. These reports, especially the latter, should have current prices of major food items, and should show shifts in prices on monthly and yearly basis. We look forward to the most current issues of these reports.

Ahead of the release of these reports, we can safely work with the surveys by media houses. Aljazeera reported that the prices of some grains crashed by as much as 40% in the past few weeks. On 26th February, BusinessDay highlighted noticeable fall in the prices of beans, yam, rice, tomatoes and garri, ranging from a decline of 23% for imported rice to 70% for tomatoes. In its monthly price survey, Nairametrics stated that the price of a 50kg bag of garri fell by 10%, a medium-sized tuber of yam by 15%, a basket of pepper by 29% and a bag of dry onions by 43%. The Guardian, on its part, reported the decline in prices as follows: 39% for a bag of beans, 40% for a heap of 120 yams, 42% for a bag of millet, 66% for a bag of maize and 71% for a bag of sorghum. While prices of certain items like eggs, fruits, beverages and packaged/processed food items are yet to come down probably due to lag effect, the decline in the prices of major raw food items is significant and should be duly recognised. This is more so when it also bucks the global trend. According to the FAO Food Price Index, the prices of globally-traded food commodities in February 2025 increased by 1.6% month-on-month and by 8.2% year-on-year.

The logical question to ask is why the significant and atypical drop in food prices in Nigeria. To President Tinubu and his agriculture ministers (Senator Abubakar Kyari and Senator Aliyu Abdullahi), the answer is straightforward: the administration’s policies and interventions in the sector are working. Another official explanation is that the improvement in security in some parts of the north has translated to increase in food production, which then is leading to supply surpassing demand. It is possible that both are valid and reinforcing explanations. But it will be good to anchor such discussions on data. Policy should not be speaking and working without relevant data. For example, how many more hectares of land have been brought into cultivation due to improved security? And if we are seeing the fruits of Tinubu policies/gains, what particular policies are we talking about and how and by how much have they impacted the total outputs of the different food items? Without data and proper tracking, it will be difficult for government to know which policy is working, what it should do more or less of and how it can sustain the gains.

There have been some other explanations, ranging from the lifting of the ban on importation of food across land borders, the pausing of payment of duties and taxes on some imported food items (that is if that well-lauded presidential promise was allowed to eventually happen), the firming up of the Naira, and reported pausing of bulk purchase of grains that UN and US agencies distribute to IDP camps etc. The combined effect of these factors would be a fall in demand and rise in supply, leading inexorably to fall in prices in line with basic economics. Signalling could also be at play here. The continuous fall in prices could have prompted/nudged the farmers and traders storing up grains and other produces in their warehouses and barns for future higher prices to start offloading their stocks in order to cut their losses in case prices plunge further. This could contribute to increasing supply, further forcing prices down.

In the absence of actual evidence, we can file all these under speculations for now. However, if one of the factors that have made the difference is the lifting of the ban on food importation/eventual implementation of the waiver of duties on rice, maize and other items, then it is gratifying that common sense finally prevailed. A good case must be made for protecting farmers. But the way to protect farmers is not by punishing the rest of the population with high food prices. If you protect farmers with unbearably high, and consistently soaring, food prices (when it is clear that we are not producing enough to meet demand), you are clearly and gratuitously inflicting pains on the many to protect the few.

There have been other contrary media reports on the reduction in food prices, and this will present a data integrity challenge for the government's statistical agency from now on. But let us suppose that the upward pressures on food prices are indeed easing, and also assume that this is due to the government loosening some of the restrictions on importation. It seems Nigerians will not enjoy the price ease for very long because the protectionist claws of the elites are very sharp and quick to unfurl.

This is bad economics. When food prices rise significantly due to import restrictions, consumers may reduce consumption or substitute with other products, potentially reducing overall demand for agricultural products. Many Nigerian farmers are net food buyers and purchase imported agricultural inputs (seeds, fertilisers, etc). Import restrictions can increase their production costs while simultaneously reducing their purchasing power as consumers. So, despite the presumably well-intended rhetoric and policies, Nigerian politicians and policymakers are the main enemies of the poor farmers they claim to protect.

This raises a broader concern about Nigeria and trade policy. After all, it is now cool to look at the United States and Donald Trump, and then use it as justification for all sorts of crazy stuff. However, Nigeria has been doing "Trumponomics" before Trump. History might be too distant for Americans to learn the consequences of bad trade policies, but Nigeria refuses to learn from its ongoing experience. The current scourge of high food prices and rising hunger is a result of bad trade policies, as the ever-so-wise Nonso Obikili noted:

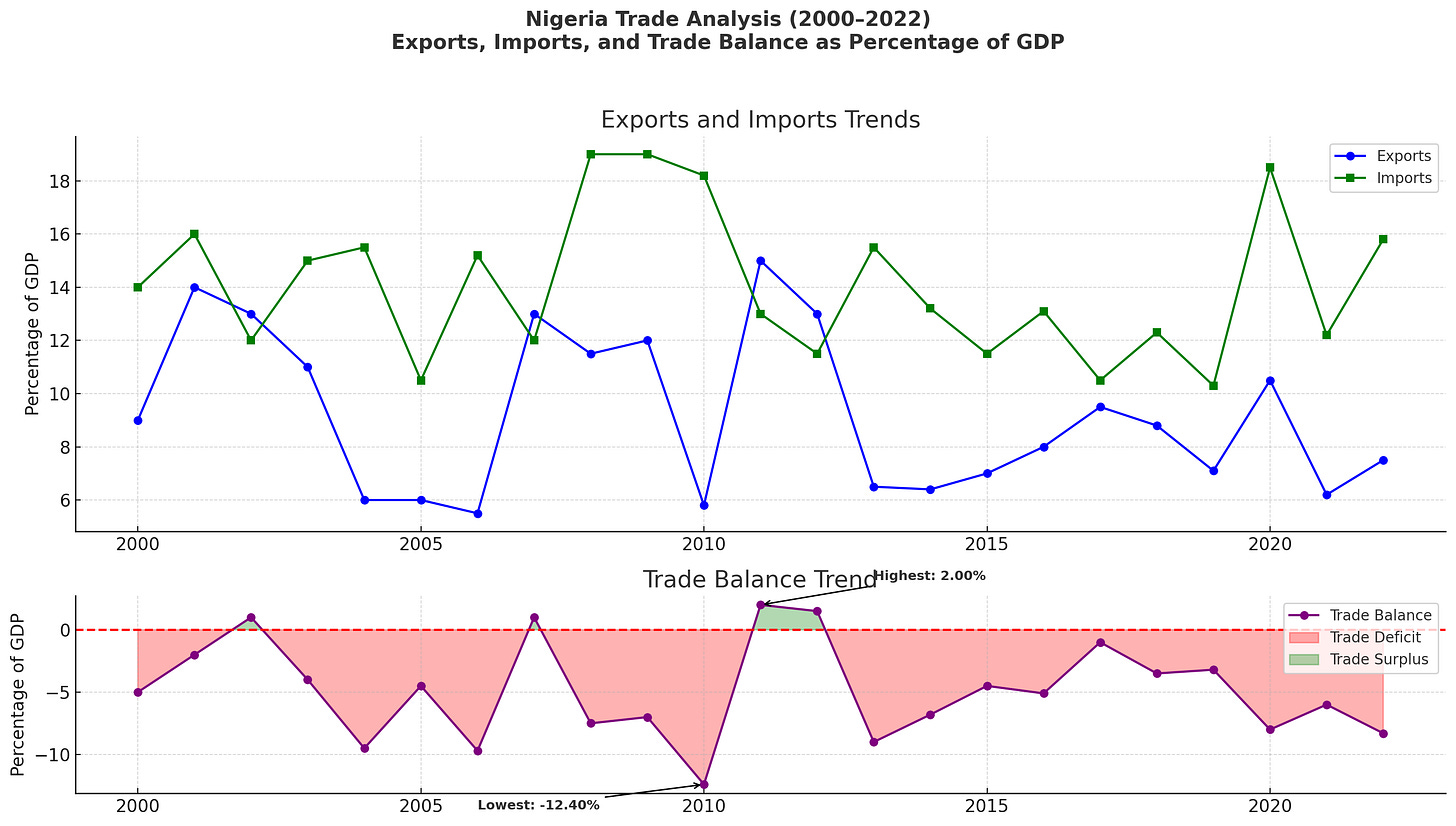

So, what happened in 2015 that could have led to this divergence in food prices between Nigeria and its neighbors? The most probable answer is trade restrictions. In response to the foreign exchange crisis in 2015, a series of restrictive trade policies were introduced, ostensibly to conserve foreign exchange. However, a significant consequence of these policies has been relatively higher food prices, which in turn have exacerbated food insecurity.

The solution, therefore, must center on relaxing food trade restrictions. As students of economics will recognize, as long as trade is functional, domestic shocks to food production—whether due to security challenges or weather-related issues—tend not to have a significant impact on prices. While such shocks may impoverish those directly affected (in the absence of insurance or social support), they rarely influence prices significantly, as localized shocks are typically too small to affect global markets.

However, in the presence of trade restrictions, these shocks have a much larger impact on prices because supply from other regions cannot easily fill the gaps created by these disruptions. Moving from a scenario of relatively open trade to one with more restricted trade introduces a price wedge and increases the vulnerability of prices to shocks.

In the context of economic development, by which I mean poor countries getting rich, free markets and free trade are not the orthodoxy. This is contrary to what most people believe. Despite the regular use of the "neoliberalism" term, nobody today can claim to advocate for free markets and free trade in development without being laughed out of polite company. Industrial Policy is not only accepted and respected in policy circles, but it is now considered necessary. The rationale is that all rich countries today have interfered in markets, engaged in protectionism, and implemented industrial policies at some point in their history. However, particularly regarding trade policies, policymakers and influential voices in Nigeria have learnt the wrong lesson from history. They think the only trick you need to succeed is closing your country off to imports. More important policies like export subsidies, research and market support, and industrial upgrading are ignored. This has weakened trade policy as a tool for development.

In the face of this persistent ignorance and misunderstanding, it is important to restate some foundational insights on trade policy. This was provided in a very cool paper by economic historian Douglas A. Irwin.1 I believe it should be a required reading for every policymaker in developing countries. Irwin provides three simple yet profound principles that help clarify why protectionist trade policies like Nigeria's frequently end in self-inflicted economic pain.

Principle One: "A tax on imports is a tax on exports."

Contrary to the beliefs driving Nigeria's trade restrictions, Irwin reminds us that imports and exports are fundamentally interdependent. Reducing imports inevitably harms exports by limiting foreign exchange availability and raising costs for exporters. Historical examples are abundant: when Brazil and India pursued aggressive import-substitution industrialisation (ISI), both saw their exports stagnate. Conversely, South Korea and Chile experienced rapid export growth when they lowered barriers, thereby boosting both imports and exports simultaneously. Nigeria’s policymakers must understand that restrictions intended to shield local producers often boomerang by hurting exporters and undermining broader economic productivity.

Principle Two: "Businesses are consumers too."

Nigerian policymakers often overlook this crucial insight when advocating protective measures. Local producers—especially in agriculture—rely heavily on imported inputs such as machinery, fertilisers, and improved seeds. Restrictions on these critical imports inevitably raise production costs, reducing competitiveness domestically and internationally. Historical precedents, such as the United States' steel tariffs in the 1980s or India’s excessive import duties on capital goods in the 1970s and 1980s, clearly illustrate the damaging consequences for businesses that depend on affordable inputs. If Nigerian agricultural policy continues to ignore this principle, it risks trapping local farmers and agribusinesses in cycles of inefficiency, low productivity, and higher costs.

Principle Three: "Trade imbalances reflect capital flows."

A prevalent misconception among Nigerian economic policymakers is the idea that trade deficits are a serious problem, and import restriction is the solution. You see this in often-repeated phrases like "Nigeria is an import-dependent country". However, trade balances fundamentally reflect domestic saving and investment patterns, not merely tariffs or quotas. Nigeria’s consistent attempt to address trade imbalances through import suppression has repeatedly failed, much like India's experience before its 1991 economic reforms. India's restrictive trade regime led to chronic trade deficits because tariffs alone cannot correct underlying macroeconomic imbalances, such as insufficient savings or excessive government spending. Nigeria, similarly, will not sustainably resolve its trade deficits unless it addresses these deeper macroeconomic factors.

Technology Gap

Irwin’s three principles illuminate precisely why Nigeria’s restrictive food-import policies consistently yield unintended economic distress—higher food prices, weaker domestic production, and exacerbated poverty. Learning from these principles would help Nigeria shift from repeating past policy mistakes toward more effective, evidence-based economic management. But the fundamental issues in agriculture extend beyond protectionism. As I have argued, improving food production requires improving agricultural productivity. A heuristic I have recently adopted comes from the economist Ricardo Hausmann. One way to design agriculture policies is to see it as a challenge of closing the "technology gap" that exists between Nigeria and the most successful food producers and exporters in the world. As Professor Hausmann astutely observed:

A narrowing education gap without a narrowing income gap suggests a widening technological gap: the world is developing technology at a rate faster than many countries can adopt it or adapt it to their needs. Economists often disregard this issue, because they think of technology as something that is embedded in machines and thus capable of flowing naturally into countries unless governments do things like restrict trade, competition, or property rights.

But technology is better understood as a set of answers to “how-to” questions. And because different people do things differently, technological adoption requires some adaptation to local conditions, which in turn requires local capabilities.

The problem of food production in Nigeria is not one of foreign competition, but of a profound technical and know-how deficit. A protectionist trade outlook will not fix the problem. It will always harm the economy and make people poorer. However, a more open trade regime by itself does not suffice.

Adapting Technology to Local Conditions

Simply importing machines and techniques will not close the technology gap. Recent research on what economists call the "Inappropriate Technology Hypothesis" offers some insights on the nature of the challenge. This hypothesis reveals that agricultural innovations are not universally beneficial but are tailored to the specific ecological conditions of the countries that develop them. When high-income countries create technologies for their pest threats and growing conditions, these innovations often fail to address the unique ecological challenges faced by farmers in places like Nigeria.

Two-thirds of agricultural patents focus on crop pests and pathogens found primarily in technology leaders like the US, EU, and Japan. Meanwhile, crops plagued by pests unique to developing countries receive significantly less technological attention. This ecological mismatch reduces technology diffusion across borders by approximately 30% and significantly impairs agricultural productivity. Counterfactual simulations suggest that inappropriate technology accounts for 15-20% of global agricultural productivity disparities. This is not a minor factor—it is a fundamental constraint on agricultural development that import restrictions cannot possibly address. Such restrictions only compound the problem by making it harder for Nigerian farmers to access what limited appropriate technologies do exist.

The solution is not to retreat behind protectionist barriers but to invest aggressively in closing the technology gap through locally-adapted innovations. Nigeria needs agricultural research and development that addresses our specific pest challenges, soil conditions, and climate realities. The rise of countries like Brazil and India as agricultural technology leaders offers a promising model, as these nations face ecological conditions more similar to Nigeria's than those of traditional R&D leaders.

Nigeria's policymakers must abandon the misguided belief that import restrictions will somehow spur agricultural productivity. Instead, they should redirect resources toward building domestic research capacity, fostering partnerships with ecologically similar countries, and creating incentives for the development of technologies specifically designed for Nigerian conditions. Only by closing the technology gap can Nigeria hope to achieve the agricultural productivity gains necessary for food security and rural prosperity. 2

Three Simple Principles of Trade Policy - Douglas Irwin

There are other challenges in the agricultural sector, like Land Reforms and the violent conflict that is sweeping through many of the farming-intensive states. I am not implying that these are not important problems, but they are not the primary concern of this essay.

Several takeaways for me, key among them includes that we are yet to fix the National Agricultural Research System (NARS) housing and responsible for managing the agricultural research centers in Nigeria, key outcome been that we continue to rely on research conducted for specific agro-ecological zones other than ours. The IFPRI did publish a damming report indicating that the admin to research staff ratio across our NARS was at a disappointingly 33:1.

Agricultural seeds research and production in the country is at an all-time low level, while yes we have seeds scattered across our markets, these seeds are mostly coded for other agro-ecological zones, as such, their germination rates are negatively impacted when used here, another challenge would also be that state and federal governments that are often the primary means of delivering seeds to farmers do not imbibe global best practices on seed packaging, transporting and storage. At least, in Kano and Jigawa states, we observed state government officials storing seeds under the same conditions they were storing fertilizer and other chemicals, in some instance, placing seeds on the same pallets used to store fertilizer.

At the Federal level, a large bulk of the practice interventions seen at the Federal Ministry of Agriculture are donor-funded, often dying off once the donor-fund pipeline dries off. The ministry and other agencies of government continue to buy agricultural seeds from sources not accredited by National Agricultural Seed Council, leading to supply of substandard seeds to smallholder farmers.

The challenges are legion, I stopped commenting on them as it became more of "conversation of the deaf".

Good read as always.