The King of F.O.O.D

Aliko DangoTAKE is back to take some more

We should start with a story that is different but relevant to the matter at hand. Recently a video circulated of former President Obasanjo talking about how Nigeria’s cement policy came to life. The five minute video is worth a watch:

In essence, Obasanjo recounts that early in his presidency he grew troubled by Nigeria’s substantial cement imports and resolved to foster local production. His enquiries into what might be required to achieve this led him to Aliko Dangote, then a trader importing cement into the country - a designation whose significance will shortly become apparent. Dangote’s explanation was straightforward: he imported cement because doing so proved more profitable than manufacturing it domestically, and thus if the president wished to encourage local production, he would need to render it financially advantageous. I have examined Nigeria’s cement industry at length elsewhere, most recently in an analysis tracing the origins of the cement policy itself.

Obasanjo committed a category error, though one not immediately apparent. The distinction is best understood with an illustration: whilst electric vehicles (EVs) and internal combustion engines (ICE) appear superficially similar - both possess wheels and are visually near-identical - an EV is technologically far closer to a mobile telephone or tablet than to a traditional motor car. For decades, Japanese and German manufacturers dominated ICE vehicle production through relentless efficiency and innovation, yet they have proven remarkably sluggish in the transition to electric powertrains. This is no accident of history: Tesla, which revolutionised the electric vehicle market in both America and China, emerged from Silicon Valley rather than Detroit, whilst the firm that now leads global electric vehicle sales, BYD, has its origins in Shenzhen, the heart of China’s technology design and manufacturing sector.

Appearances can deceive: things may seem identical whilst being fundamentally distinct. Obasanjo sought a cement manufacturer but conflated this with a cement trader, and so turned to Dangote. The actual problem, however, was rather different: manufacturers halfway across the world could deliver cement to Nigeria more cheaply than it could be produced domestically. Nigeria possesses abundant limestone deposits, and cement production - whilst perhaps amongst the industrial world’s more impressive achievements - is not technologically complex. What was required was the marriage of Nigeria’s natural endowments with two critical competencies: engineering skill to harness appropriate technology and achieve rigorous cost control, and managerial expertise to orchestrate production efficiently. Only through such combination could domestic cement be manufactured at prices sufficient to render imports commercially unviable.

A trader and his margins

This was never a task suited to a trader. A trader’s singular preoccupation is with margins: he may possess scant understanding of how the product he handles is actually made, but excels at purchasing low and selling high. It is for this reason Nigeria has derived negligible benefit - beyond the creation of a handful of dollar billionaires - from local cement manufacturing, particularly when assessed by the things for which cement serves as an input. As I have documented extensively elsewhere, Nigeria has acquired no mastery whatsoever of the underlying cement technology. Dangote, a trader, merely purchases the technology from China at low cost and sells it to Nigerians at a markup.

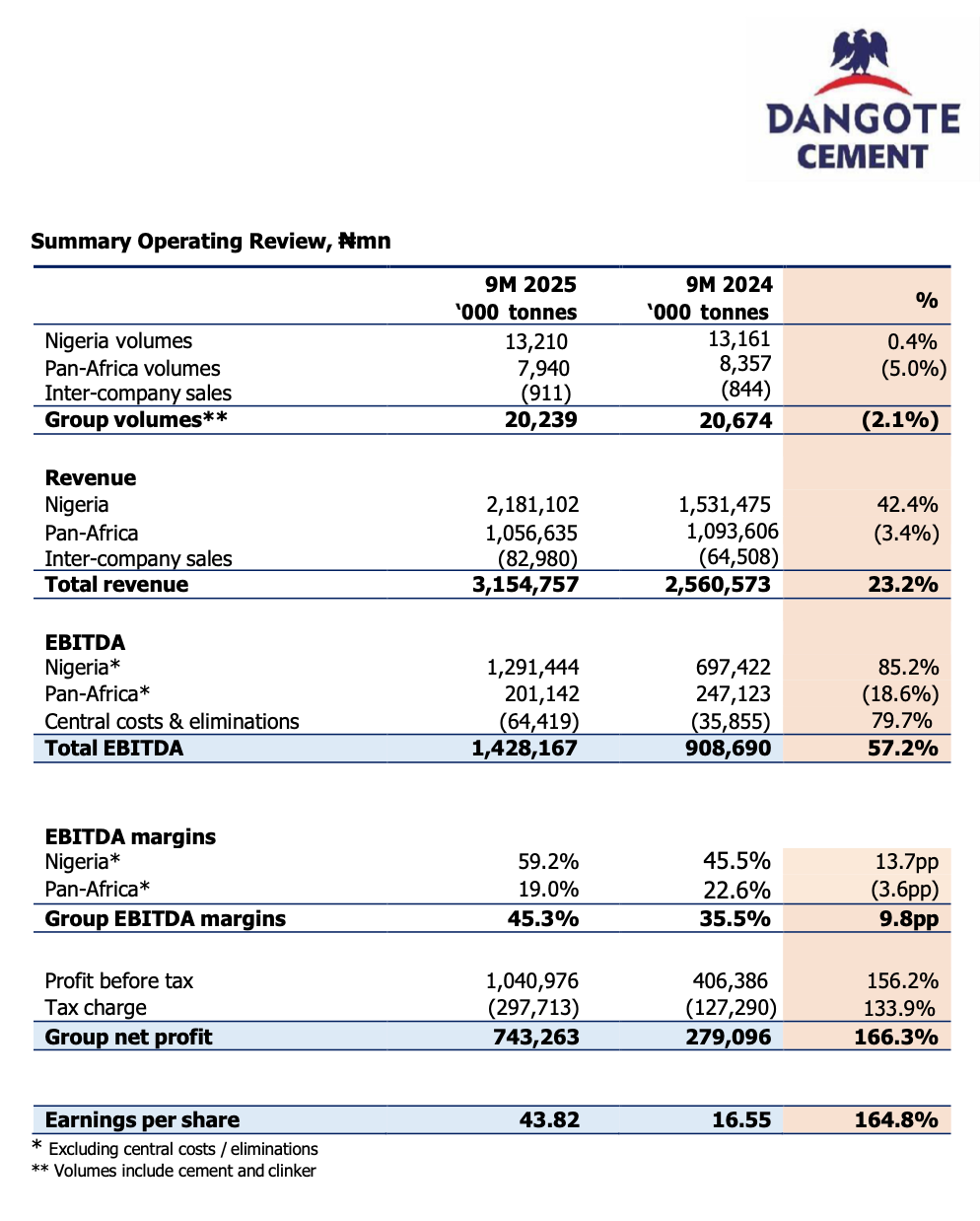

Consider the latest set of results released by Dangote Cement for the nine months of the year to September 2025:

Compared with the corresponding period in the previous year, the actual volume of cement sold in Nigeria remained virtually static, yet revenues rose by more than 42% whilst EBITDA surged by 85%. When a company sells an identical quantity of product for substantially greater revenue and profit - particularly when manufacturing costs increased by only 4% - there is only one explanation: pricing power. This has been the recurring narrative of Dangote Cement for years; during one twelve-month period alone, I documented six separate price increases imposed seemingly at will. Here is a quote from an Economist article from 2014: “Dangote’s margins in Nigeria are 63%, compared with the 30–40% margins typical in other ‘frontier’ markets. And after several years of stability, the firm is set to raise its domestic prices further.”

One might reasonably contend that Dangote need not possess comprehensive engineering expertise to operate a cement enterprise successfully; after all, competent personnel may be employed to supply whatever technical knowledge he lacks. The reality, however, is rather different. He dominates his commercial empire as an outsized personality, involving himself in matters as trivial as determining which subordinates receive bonuses and what amounts, whilst simultaneously making far more consequential decisions - such as constructing an enormous refinery as a single-train facility - in defiance of expert counsel.

The focus is relentlessly on maintaining and increasing margins and anything that threatens that will not be tolerated. When you hand your industrial policy to a trader, this is what you get.

Petrol F.O.O.D

On the 21st of October, President Bola Tinubu, approved the introduction of a 15% import duty on petrol and diesel “to be assessed on the Cost, Insurance and Freight (CIF) value at discharge.” The reasons for the import duty are stated explicitly (emphasis mine):

5. In alignment with the updated technical proposal, it is recommended that an ad-valorem import duty of 15 percent (15%) be introduced on Premium Motor Spirit (PMS) and Diesel, applied to the Cost, Insurance, and Freight (CIF) value at discharge. At current CIF levels, this represents an increment at approximately N99.72 per litre, which nudges imported landed costs toward local cost-recovery without choking supply or inflating consumer prices beyond sustainable thresholds. Even with this adjustment, estimated Lagos pump prices would remain in the range of N964.72 per litre ($0.62), still significantly below regional averages such as Senegal ($1.76 per litre), Cote d’Ivoire ($1.52 per litre), and Ghana ($1.37 per litre).

6. The tariff is not revenue-driven but corrective, aimed at aligning import costs with domestic realities while preserving affordability. Payments would be made into a designated Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN) revenue account under the Nigeria Revenue Service (NRS), with verification by the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA) before discharge clearance. Implementation would commence after a 30-day transition window, allowing importers to adjust cargoes already in transit and ensuring a smooth rollout without market disruption.

It is exceedingly rare to encounter such candour committed to print. The reasoning is straightforward: imported petrol, even after accounting for shipping costs, somehow arrives in Lagos at prices below those of Dangote’s domestically refined product. This state of affairs is deemed untenable, and the proposed remedy is thus to inflate the price of imports sufficiently to preserve Dangote’s competitive position. What circumstances within the Dangote Refinery might account for this peculiar situation - wherein locally refined petrol cannot compete on price despite the facility being newly constructed with presumably modern technology and notwithstanding various government incentives and subsidies? No one knows, and no one is permitted to enquire. The refinery’s pricing is simply accepted, ex cathedra, as the prevailing domestic rate.

We built this city on rock and roll

Within the N964 per litre that the government has deemed appropriate for the Dangote Refinery’s “cost recovery”, what margin is embedded? Is it 5%, or perhaps 25%? Establishing this figure matters for several reasons. Foremost, it permits benchmarking against international refining peers. If, for instance, European refiners earn an average margin of $8 per barrel, what constitutes a reasonable margin for a Nigerian refiner once country-specific risks and operating costs are factored in - $10 per barrel, or $5? Whatever the answer may be, it cannot credibly be derived by simply accepting the figure advanced by Dangote Refinery itself and enshrining it as national policy.

The second consideration is that the Dangote Refinery did not materialise in isolation; rather, it benefited from substantial state support. Consider first the land itself: 2,635 hectares were acquired for $100 million, a transaction Dangote himself characterised as a “good deal”, though the state has never disclosed any documentation regarding the sum it received from Dangote Refinery, despite civil society organisations mounting legal challenges to obtain details of the purported sale. Even accepting Dangote’s figure at face value, this amounts to approximately $15,000 per acre - a favourable price by any measure. Consider further that the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) bent itself into contortions to ensure the refinery never lacked foreign exchange during construction, providing it at preferential rates during the era of multiple exchange rate regimes. Dangote himself acknowledged receiving “only” $2.7 billion from the CBN.

Consider too that the entire Nigerian banking sector mobilised with unprecedented coordination to secure the refinery’s requisite funding. In 2013, when the project was still envisaged at 400,000 barrels per day, no fewer than nine Nigerian banks syndicated a $3.3 billion loan facility. By 2015, a BusinessDay analysis revealed that 9% of all foreign exchange loans extended by Nigeria’s tier-one banks were committed to the Dangote Refinery project alone. In 2018, Dangote informed Reuters that the Central Bank would furnish guarantees for approximately N575 billion in local currency over a ten-year period. By 2022, a bond issuance intended to part-finance construction costs and service debt during the build phase involved virtually every financial institution of consequence in Nigeria.

Consider further that the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation assumed a 20% stake in the refinery in 2021, valued at $2.76 billion, of which $1 billion was paid immediately. It was subsequently claimed that the NNPC failed to remit the outstanding balance, whereupon the stake was reduced to the 7.2% actually paid up. Consider also that once the refinery commenced operations, the regulator - the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA) -granted it a waiver permitting diesel sulphur content to exceed the standard 200 parts per million limit during the operational ramp-up phase. Consider finally that the NNPC has since become the refinery’s principal crude oil supplier with a large chunk of that crude paid for in naira, not dollars, to insulate the refinery from any foreign exchange volatility. The company is based in a free trade zone, does not pay company taxes, VAT or duties on imported raw materials or equipment and is free to move 100% of its profits wherever it deems fit.

When all of this is taken into account, should one simply accept at face value that a refinery producing fuel in Nigeria cannot match international pricing? What further concessions might be required - free crude oil, perhaps? If, after such comprehensive support, a 15% levy - to be paid indefinitely by ordinary Nigerians - remains necessary to “nudge” import prices towards domestic “cost recovery”, then serious questions must be asked before unfettered pricing power is ceded to Dangote and his refinery.

There is something even more disturbing as shown in the chart below from a September 2025 presentation by S&P Global:

In plain terms, during the thirty-day period examined in the report, petrol could be purchased in Lomé, Togo for just under N800/litre. Simultaneously, marketers were paying N820/litre to procure the same product from the Dangote Refinery in Lagos. Naturally, transporting fuel from Lomé to Lagos incurs freight costs, which brought the landed price in Lagos to just over N840/litre. Given that Dangote’s N820 price presumably already incorporates a respectable margin, several observations warrant attention.

Lomé serves as West Africa’s principal ship-to-ship (STS) trading hub for petrol and refined products. Large “mother” tankers deliver cargoes from export refineries across Europe, the United States Gulf, and the Middle East, which are then traded and subdivided into smaller parcels through STS transfers. The “Gasoline STS Lomé” price represents a delivered-to-Lomé benchmark that already incorporates long-haul ocean freight, insurance, and the customary STS transfer premiums required to convey the cargo from origin refinery to the Lomé anchorage. Remarkably, Dangote’s product - refined in Lagos itself - somehow emerges more expensive than fuel shipped to Lomé from distant refineries. Only once the additional freight costs from Lomé to Lagos are factored in does the Dangote product become marginally cheaper. Yet a 15% import duty is then applied to the foreign alternative. The inevitable outcome is clear: Dangote Refinery will augment its margins by ensuring that the foreign price plus 15% tariff becomes its target rate. This is precisely how F.O.O.D works.

Jamnagar, my Jamnagar

Aliko Dangote has repeatedly cited the Jamnagar Refinery, constructed by India’s Reliance Industries, as the principal inspiration for his own refinery project. A Bloomberg report from last year noted that “Dangote visited Reliance’s Jamnagar plant - the world’s largest refining complex - whilst seeking inspiration for the 650,000-barrel-per-day facility near Lagos that commenced production in 2024.” In an interview four years ago, he elaborated upon this inspiration, observing that Indian entrepreneurs had established refining capacity of approximately five million barrels per day in a country possessing considerably less oil than Nigeria.

It is instructive to consider what transpired in India following the Jamnagar refinery’s commissioning in July 1999. Since the 1970s, India had maintained differential import duties designed to favour domestic refining: crude oil attracted lower tariffs than refined products. Yet in the 2000 Budget, delivered after Jamnagar commenced operations, these duties were actually reduced - from 20% to 15% on crude, and from 30% to 25% on refined products (PDF, Section II[D]). I confess to doing a double take when I saw this: how could the Indian government have lowered tariffs on imported fuel immediately after a vast new domestic refinery had opened? Add to this the fact that by April 2002 the government had dismantled the Administered Pricing Mechanism (APM) that had guaranteed returns and assured off-take for refineries since the 1970s. Under this arrangement, refinery margins were administratively set to cover costs whilst delivering approximately 12% post-tax return on net worth, with an Oil Pool Account cushioning consumers through cross-subsidisation. This framework had shielded all domestic refineries, whether publicly or privately held. In effect, this represented India’s version of “subsidy removal.”

The explanation for this is perhaps less complicated than it might appear: Jamnagar was price-competitive from the outset. The clearest evidence lies in the rapidity with which the company scaled up its exports within a few years of commencement. A report from India’s Business Standard merits quotation here:

Barely into the third year of its operations in 2002-03, the Reliance Industries’ refinery at Jamnagar has surpassed all public sector refining companies in the export of petroleum products. In the first year after the dismantling of the administered pricing mechanism in the oil sector, the 27 million tonne Reliance refinery exported 6.5 million tonne of petroleum products. The joint sector Mangalore Refinery and Petrochemicals Limited (MRPL) emerged a distant second with 1.9 million tonnes of exports. While Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited (HPCL) came third with 5,96,000 tonnes of exports, Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited (BPCL) exported 4,83,000 tonnes. Indian Oil Corporation (IOC) was fifth with 3,96,000 tonnes. With the increase in the domestic refining capacity, the country has been witnessing a jump in petroleum product exports. In 2000-01, the exports, at Rs 7,672 crore, were 999 per cent higher than in the previous year. In the following year, at Rs 8,285 crore, the country became a net exporter of petroleum products for the first time.

International buyers of fungible commodities such as petrol or diesel are indifferent to provenance; they seek the best price and nothing else. Just as Dangote Cement has conducted virtually no cement exports from Nigeria - preferring instead to construct plants abroad, for why sell a bag of cement cheaply overseas when one can command far higher prices domestically? - precisely the same strategy is poised to unfold with petrol. Nigeria will become a protected high-margin market, this arrangement enforced by government policy for Dangote’s benefit, whilst the remainder of the world remains a mere afterthought. The discipline that exports force on you when you have to sell to people who only care about price and have other choices, will be completely blunted.

As we have witnessed with cement, the trader whose devotion to margins eclipses any consideration of innovation, technology, or industrial advancement will wield his pricing power to inflate those margins, regardless of the broader cost. Many feared precisely this outcome, and as the adage - probably never uttered by any wise man - reminds us: just because you are paranoid does not mean the world is not indeed conspiring against you. Yet this entire edifice of protection and subsidy has been erected before the Dangote Refinery can even satisfy domestic petrol demand or demonstrate that the facility functions as intended. The pattern is unmistakable, the precedent clear, and the consequences entirely foreseeable.

F.O.O.D is ready. And if you are a Nigerian in Nigeria, you’re the one on the plate.

The trading mentality is VERY old culturally and entrenched. See Mansa Musa

The underdevelopment of OML 71 and 72, located in the Southeastern Niger Delta near Bonny Island, reflects a critical gap in Nigeria’s drive to increase crude oil output. Operated by West African Exploration and Production Company (WAEP) — 45% owned by the Dangote Group with minority participation from First Exploration and Petroleum Development Company, and 55% by the Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC) — the assets are yet to reach full production capacity. OML 71, currently undergoing Long-Term Well Testing, has its first oil target of about 20,000 barrels per day delayed to late 2024.

This delay underscores ongoing challenges in project execution, funding, and field development. For Nigeria, this setback limits short-term crude supply growth and delays gains in foreign exchange and energy security. Accelerating indigenous field development like OML 71 and 72 is therefore essential to meeting national production targets and reducing reliance on International Oil Companies (IOCs).