The Great Tax Bet

Bola Tinubu, Art Laffer, and the ''hidden'' ideology of policymaking in Nigeria

I came to the debate about the new Nigerian tax reforms and laws very late. Admittedly, other important aspects of it were drowned out by the political theatre of the VAT reforms. The changes signed into law by President Tinubu are not mere administrative tweaks; they represent the most consequential shift in Nigeria’s tax architecture in over a decade.

However, much credit to my co-blogger for breaking the silence with his recent essay, which laid out the scale of the reform and its implications for personal income tax. The Nigerian Tax Act aims to simplify the tax code, eliminate dozens of minor levies, and establish a higher threshold before the top rate applies, resulting in a quite radical redistribution of the tax burden, as Feyi succinctly sums it up:

….if you're a high earner, this new tax bill is pretty good for you. Nigeria’s top rate now sits so far up the scale that almost nobody will ever pay it. I imagine a few Nigerian states will see no one paying tax at 25%.

What does this all mean? As I say, I'm neutral on raising taxes in general. Still, I'm somewhat surprised there was hardly any debate on this aspect of the NTA. The changes to the top rate of tax are fairly dramatic. In Nigeria's devolved system, income taxes are collected by states, so I would have expected governors to generate a racket about this given it's a missed opportunity to increase their tax take. But then again, Nigerian states are in the rudest financial health they've ever been (a topic for another day), so maybe they didn't care that much. Maybe the nominal disguises the real effect for middle to lower earners, hence why there's been no noise from them. If you're currently earning N2.3m for instance, the highest rate of tax you're paying is 21%. Once this law comes into effect, you drop into the 15% bracket, which looks like a tax cut for you.

I think it is fair to say that the Nigeria Tax Act, which instigated fierce debates and controversy, is the biggest policy change in the lifespan of the current government since the early months of fuel subsidy removal and exchange rate liberalisation two years ago. Unlike those two policies — both widely criticised as haphazard and poorly implemented—the tax reform process was anything but accidental. From the outset, the Tinubu government was quite deliberate and clear that tax reforms were a priority. The chairman of the presidential committee, Taiwo Oyedele, who led the effort, set a tone of openness and intellectual seriousness.

In a recent interview, he spoke candidly about the pressures of the role, including the political landmines, the misinformation campaigns, and the personal sacrifices required to keep the process on track. The committee undertook months of consultations, moderated public debates, and reframed the reform not as a revenue grab but as a chance to repair a broken system.

Oyedele articulated three guiding principles: the tax laws had to be “people-centric” to stop taxing poverty, “efficiency-driven” to fix leakages and improve collection, and “growth-focused” to support businesses and stimulate economic activity. Transparency, too, was central. The new laws impose stricter reporting standards on revenue agencies and strengthen oversight by the National Assembly. The ambition, he said, was not just to write a better tax code but to implement it properly—digitising administration, closing a 70% tax gap, and building public trust in a system long regarded as opaque and extractive.

These are lofty goals. Designing a tax policy that is fair to the poor, promotes economic growth, and increases government revenue through greater efficiency is an attractive vision. But it is also one embedded with strong claims—claims that deserve to be weighed carefully against the realities of how tax systems function in practice, and the evidence of what has worked in comparable developing economies. In Nigeria’s case, this means asking three hard questions: does the reform achieve fairness in who pays and who benefits; can it be implemented effectively by overburdened institutions; and will it deliver the fiscal resilience needed in an economy still tethered to oil? Lofty ambitions often falter under the weight of institutional weakness and political incentives. Nigeria is no stranger to this pattern.

Why Tax?

Let me take a step back by asking a deceptively simple question: What is a tax system for? This is a question that any serious tax system or reform must grapple with. At its core, taxation serves three broad purposes. First, it funds the provision of public goods - schools, roads, security, healthcare - the infrastructure of a functioning state. Second, it redistributes income, reflecting a collective decision about the degree of inequality a society finds acceptable. Third, it corrects market failures, such as pollution or congestion, by imposing costs on harmful activities. These functions are conceptually straightforward, but in practice, they are deeply contested. Every tax system embodies a set of moral and political choices about who pays, how much, and to what end.

A good tax system, then, cannot be judged by revenue alone. It must balance competing principles: efficiency - raising funds without distorting economic activity; equity - sharing the burden fairly across different income groups; simplicity - being easy to understand and comply with; and transparency - ensuring citizens know what they are paying and why. These goals are not always compatible. Measures that promote equity, such as progressive rates, can create efficiency losses if poorly designed. Efforts at simplification can undermine transparency if they mask redistributive effects. The reality is one of trade-offs: no system perfectly satisfies all ideals.1

These trade-offs are especially stark in developing economies. Widespread informality, low institutional capacity, and weak enforcement make ambitious tax systems harder to administer. The revenue base is often narrow, with a small formal sector carrying the weight of funding public goods. At the same time, political incentives frequently align against broadening the base: powerful elites resist measures that would subject their wealth to scrutiny, while governments fear alienating a restive citizenry by raising rates or tightening enforcement. The result is often a patchwork of taxes - regressive consumption levies, nuisance fees, and poorly enforced income taxes - that generate little revenue and entrench inequality.

In such settings, reformers must grapple not only with economic theory but with political economy: who gains, who loses, and who has the power to resist. They must also confront behavioural realities. Taxpayers respond to new laws by changing how they earn, spend, and report income. High rates can drive avoidance or outright evasion; aggressive enforcement can push more activity into the shadows. A successful tax system, particularly in fragile states, requires more than legislative ambition. It demands administrative capacity, political consensus, and a degree of public trust that is often lacking. This is the terrain that Tinubu’s tax reforms must navigate to have a shot at success.

Taxation in Developing Countries

Experience across Latin America, Africa, and Asia suggests a sobering reality: while good tax policy can be designed on paper, its success depends on the messy realities of administration and politics.

In many countries, reform was born out of crisis. Hyperinflation or fiscal collapse created openings for governments to simplify complex tax codes, broaden bases, and rationalise rates. Some, like Bolivia, opted for a radical “big bang” approach; others, such as Colombia and Morocco, pursued gradual transitions. Both strategies had merits, but neither could overcome weak institutions. Without effective tax administration, even the most elegant reforms faltered.2

Administrative capacity consistently emerged as the decisive factor. Countries that invested early in strengthening revenue authorities - digitising systems, professionalising staff, and systematising collection processes - achieved more durable results. Withholding mechanisms and third-party reporting, where institutions like banks and employers supply tax-relevant data, proved particularly effective in contexts of limited enforcement capacity. Indonesia’s focus on building institutions before passing new laws raised tax revenues significantly within five years. By contrast, Mexico and Jamaica saw technically sound reforms stall when enforcement gaps and public distrust undermined compliance.

Political economy was equally critical. Tax systems create winners and losers, and entrenched elites often resist changes that threaten their privileges. In many countries, statutory tax burdens diverged sharply from real ones due to widespread evasion, especially among the wealthy. Efforts to improve compliance—through tax amnesties, international information sharing, or targeted audits—have met with mixed success. Successful governments, such as Turkey, linked tax reform to broader national goals, building political consensus and public trust.

Simplicity in tax design also stands out as a recurring theme. Systems with narrow bases and high rates tend to create perverse incentives for avoidance and evasion. By contrast, broader bases and moderate rates not only improve efficiency but also enhance fairness by limiting special privileges. Even value-added taxes (often criticised as regressive) can have redistributive effects in economies where low-income households largely consume from informal markets. In fragile states, rough justice—systems that function tolerably well despite imperfections—have often proved more grounded in the reality of their economies.

The Nigeria Tax Act - Examining the Core Goals

The 2025 tax reforms were packaged into four sweeping laws. But as Feyi's essay examined in detail, it is the Nigeria Tax Act’s overhaul of Personal Income Tax that carries the most immediate implications. A new tax-free threshold of ₦800,000 ($500 annually) exempts most low earners. At the same time, a top rate of 25% applies only above ₦50 million - a level so far removed from everyday incomes that it effectively spares almost all Nigerians. In dollar terms, the top rate now begins at $31,000, up from $20,000 under the previous system. High earners benefit from a quiet tax cut; middle-income earners see modest relief; and for the working poor, compressed brackets may push them into higher bands sooner than expected.

Is It "Pro-Poor"?

On its face, the new tax regime appears generous to low-income Nigerians, exempting anyone earning less than ₦800,000 annually. Yet this gesture may be less significant than it seems. With pervasive informality and widespread poverty, most Nigerians were already outside the tax net in practice. At the upper end, the shift of the top rate threshold to ₦50 million ensures that high earners - already a vanishingly small group - remain largely untouched. This creates the illusion of progressivity while narrowing the tax base further. For the middle class, modest reductions bring some relief, but the compressed brackets below suggest that lower earners may face steeper marginal rates earlier in their income growth, a subtle reversal of pro-poor rhetoric.

Tax Administration Matters

The administrative changes promised alongside the tax changes - digitisation, unified taxpayer IDs, and a more independent revenue service - suggest a break from Nigeria’s patchwork of opaque and inefficient systems. In other countries, such efforts have yielded gains: Rwanda’s point-of-sale monitoring improved VAT compliance; Pakistan’s performance-based bonuses for tax agents boosted collections without increasing harassment. But these successes were not the result of technology alone. They required skilled, motivated frontline officials and political commitment to enforcement.

In Nigeria, these preconditions are far from assured. Less than a week after the presidential assent, many commentators and stakeholders were already warning of landmines: institutional overlaps between agencies like the Nigerian Customs Service, Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC), and the new Nigeria Revenue Service; unresolved conflicts with laws such as the Petroleum Industry Act; and a six-month transition period that may understate the scale of the work required. Turf battles and litigation loom large. State-level tax authorities - responsible for collecting 95% of PIT - may resist reforms that threaten their autonomy or revenue streams. Even within federal agencies, loss of Cost of Revenue Collection (CORC) commissions could provoke bureaucratic sabotage. These are not abstract concerns. Similar patterns have played out before, where reforms were quietly gutted in implementation through side deals and political compromise.

Without visible improvements in public services and a restoration of trust between citizens and the state, Nigeria’s tax reforms risk being perceived as yet another mechanism of extraction, deepening the country’s long-standing tax morale problem. Digitisation and consolidation are necessary but insufficient. They must be accompanied by a behavioural and cultural change of the bureaucracy towards effective service delivery. This will require a rare alignment of political incentives at the federal and state levels.

Rebuilding the Fiscal State

The new tax framework is positioned as people-centric rather than revenue-driven - a politically palatable stance in an economy battered by inflation and rising poverty. But fiscal resilience demands more than compassion. With years of oil revenue struggles and debt service swallowing a significant portion of federal revenue, Nigeria’s reliance on a narrow tax base is unsustainable. The government has set a target of raising the tax-to-GDP ratio to 18% within the current Medium-Term Expenditure Framework, up from around 10–13%. Such a leap would be unprecedented without major structural and administrative changes.

The heavy reliance on exemptions and high thresholds means the tax base may become even narrower than widened. Revenue targets are likely to remain volatile, and clever rate adjustments will be deployed to do the heavy lifting. This will increase the fragility of the tax system. Experience from other developing countries suggests that raising rates in fragile tax systems often backfires, driving firms and individuals further into informality and encouraging tax evasion. Indonesia’s recent reforms offer a cautionary lesson: efforts to increase compliance through enhanced audits, third-party data integration, and stronger enforcement yielded more durable revenue gains than equivalent increases in statutory tax rates. In Nigeria’s context, where informality is widespread and high earners are adept at exploiting loopholes, administrative strength is likely to matter more than headline rates.

But perhaps more crucially, these reforms must be understood not merely as a response to immediate fiscal pressures but as the first step toward building an inclusive fiscal state. A system where taxation and public spending reflect a binding social contract between government and citizens is essential for long-term stability. Without this, even success in stabilising oil and gas revenues - the government’s other priority - could undermine the gains. Nigeria’s history of rentier politics illustrates how windfalls from resource rents can foster profligacy, erode accountability, and undermine incentives to develop non-oil revenue capacity. The danger is that once crude receipts rebound, the momentum for reform will dissipate, leaving the state trapped in its old extractive habits.

Taxation and Growth

A fourth but equally important claim that should be examined is growth. The tax reform has been presented as “pro-business” and growth-oriented - lower effective tax burdens for high earners and the elimination of over 50 nuisance taxes are meant to spur investment and entrepreneurial energy. The intuition is familiar: lighter taxes, fewer distortions. Yet the empirical relationship between taxation and growth is far from straightforward. While punitive tax rates can discourage work, saving, and investment, cross-country evidence suggests moderate rates rarely suffocate growth. More crucial are the uses of tax revenue: public investment in infrastructure, education, and health has stronger and more reliable pass-through effects on productivity and aggregate demand.

I will confess a bias here. I prefer my government to be "pro-market", meaning that policies should enforce an open and competitive business environment that promotes innovation in product and service delivery, rather than "pro-business" policies that too often devolve into corporate capture and protection of incumbents. However, Nigeria’s regulatory landscape is rife with extortion and bureaucratic incompetence that is hostile and damaging to commerce. This may partly explain the instinct to appease or pander to the rich with tax cuts as an incentive to invest. But some evidence suggests that complex and fragmented tax systems are bigger inhibitors of private investment than the top tax rate. Overall, tax reform by itself, without strategic and complementary public investment in productivity-enhancing sectors of the economy, will not deliver economic growth.

I want to close on a speculative note. What I found interesting, reading and thinking about the tax reform, is not the technical details, but the instincts that inform one of its key underlying propositions. As Feyi noted in his piece, which I have also repeated, the laws deliver significant tax cuts, particularly for high earners. This is justified as a way to broaden the tax base, stimulate growth, and improve compliance. But the real reason lies in fundamentally held beliefs. I suspect President Tinubu genuinely believes tax cuts will broaden the tax base and increase government revenue.

Nigerian politics is often criticised for lacking ideology. Political parties and politicians do not run widely divergent ideas or policy platforms. This is a fair critique. The marketplace for political ideas in Nigeria is very thin, and there is a poverty of policy entrepreneurship. But this does not mean that policies are completely lacking in ideological logic. This ideological logic often follows the beliefs or instincts of the leader. As I wrote in a previous essay:

…Political leaders simply want to stay in power, and the policies they choose often reflect this priority. But despite the incentive to hold on to power, politicians, like the rest of us, are imbued with sensibilities for many folk economic theories. My way of looking at this is that powerful political actors like presidents often have some ''basic instincts'' or intuitive preferences for certain policies. These instincts are informed by ideas, for as the great economist John Maynard Keynes once said - ''Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually slaves of some defunct economist."

The instincts of political leaders shape the behaviours of the policy advisers around them, and they almost always tend towards conforming with the instinct of the leader and not dissenting.

This was quite evident during the years of Muhammadu Buhari. Even though Buhari never openly professed any ideology, his instincts were disposed towards subsistence agriculture, import-substitution, and a strong currency as the drivers and markers of prosperity. Despite the presence (perhaps occasionally) of advisers who knew better around him, Buhari was still able to steer policy towards his instincts and set the central bank on a record-breaking path of monetary finance

Just like Buhari, President Tinubu also has his beliefs and basic instincts that can be gleaned from speeches, interviews, and writings. He does not believe in price control. He believes real estate is an important industry for growth. He likes commodity exchanges - and at various times he has expressed his beliefs in a bizarre mix of Keynesian Fiscal Policy, Countercyclical Fiscal Policy, and monetary financing of fiscal deficits (ironically, his government is struggling to clean up the mess of the last round of monetary financing). These beliefs are important because they are the ideas to which he will be most responsive.

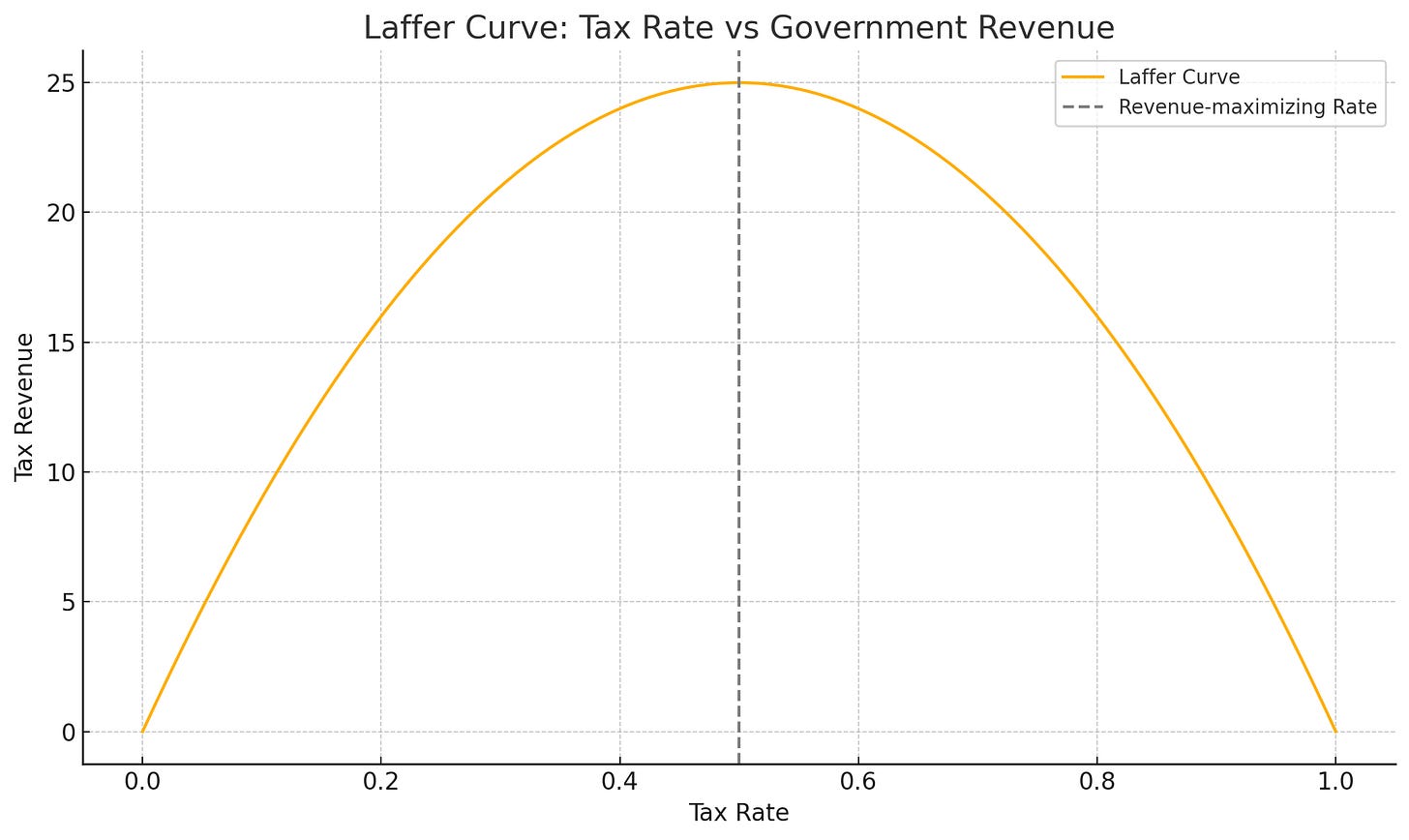

If Tinubu’s presidency believes, coherently or otherwise, that cutting taxes will "pay for itself" by unlocking growth, then it sets the tone for Nigeria’s wider fiscal strategy under his leadership. Policymakers will shape reforms, however technical, to flatter the instincts of political leaders. Advisers tend to conform rather than dissent. The relationship between tax rates and government revenue is an old idea, but the modern incarnation of it is often ascribed to American economist Arthur Laffer, an economic adviser to former American president Ronald Reagan. Laffer was claimed to have supposedly sketched the idea on a napkin during a meeting with politicians.

The Laffer Curve is empirically complicated. The shape and peak of the curve (see diagram) vary depending on the economy, the tax base, the kind of tax (income, capital, corporate), and time. For most developed countries, empirical studies tend to show that current tax rates are well below the revenue-maximising point. That means cutting taxes is unlikely to increase revenue in these contexts. In some developing economies, where tax compliance is low and avoidance is rampant, the Laffer effect might be more relevant. In economies with high informality, raising rates often pushes activity underground; hence, cutting taxes on the formal sector might broaden the base instead, but overall, the evidence on the effects of tax cuts on revenues in developing economies is not robust.

Regardless of the empirical sensitivity of the Laffer Curve, it is a useful conceptual tool to show that more taxes do not always equal more revenue. But it is also prone to political abuse. When someone argues that "cutting taxes will increase revenue", they are assuming we are on the right-hand side of the curve, which, in practice, is rarely the case for most income brackets or tax types. The relevant question for Nigeria is whether these tax cuts will deliver additional benefits beyond just simplifying and strengthening tax administration. This is the huge bet that the Tinubu government has taken. Now we wait and see what it pays.

Taxing Ourselves: A Citizen’s Guide to the Debate over Taxes - Joel Slemrod and Jon Bakija

Tax Reform in Developing Countries - Wayne R. Thirsk

A couple of thoughts (sorry if it ends up being long) on the current "tax reform" and just some of the things I observed:

1). Virtually all the discussion was about VAT and redistributing revenue. No talk about its effects on savings, investment, productivity and economic growth. That says a lot about the nature of the Nigerian state and the quality of discourse.

2). To the best of my knowledge, no one made any reference to the Laffer Curve and how one cant just wish to have more revenue and it comes just like that through some wishful thinking without a fairly sophisticated understanding that this is not a wish-it-on-paper-and-it-happens issue. Even if some might not agree with the curve and its theorems, addressing it at some length shows that one has done their homework and thought through things.

3). Perhaps more disturbing to me and why even though I support the measly corporate tax reductions I ultimately don't support this bill. It aims to increase the portion of national output which the Nigerian federal government consumes with the aim being 18% of GDP.

We must keep in mind that Nigeria has been in the middle of economic stagnation for a decade. Which is another way of saying that a massive tax hike bill just took place in the middle of a decade old stagnation.

Lets even say what I just said is dismissed as the rantings of a "market fundamentalist", lets look towards Keynes. Yes, Keynes supported counter cyclical policies in these kind of circumstances, but even Keynes never supported tax increases under these circumstances. Even by Keynesian logic (which Tinubu implicitly subscribes to in his fiscal policies), more that doubling the tax net in the middle of a decade old economic stagnation is wrong policy.

Further more lets even do a worldwide comparison of the percentage of national output consumed by the central government (not sub-nationals) in a number of emerging markets:

China: 11.6%

Taiwan: ~12.5%

Singapore: ~13.7%

UAE: ~7.1%

Indonesia: ~10.2%

Malaysia: ~11.8%

As we can clearly see, they don't excessively consumer their national output. And we wonder why they are growing in leaps and bounds.

Truth be told. The whole 18% (their minimum) figure is an IMF fiction which has more to do with ensuring that international creditors are paid than anything to do with productivity, economic growth and the welfare of Nigerian people. But the Nigerian technocratic class has been gaslite into thinking that attempting to double the tax drag net in the middle of a decade old stagnation would bring growth.

4). Whether Nigerians realize it or not, in crafting such a bill they are competing with the almost 200 countries of the world for resources and business. I just did not see that awareness anywhere talking in terms of global competitiveness.

I know Feyi has argued that this till is good in high earners. I beg to differ. His logic is that its a small crop of Nigerians who earn so high. But one has to think about it in terms of such a crop increasing if the economy improves (which I am not sure with this bill).

The 25% kicks in around $30,000. Nigeria should have raised that rate to as high as $80,000 or even $100,000. Ill give another reason. Doing such can be a very good way of attracting in talent and capital into the Nigerian economy; goes back to what I say about discourse about global competitiveness totally missing from this whole debate.

One should stack the personal rates against rates in emerging markets - Nigerians love to talk big but sell themselves short. For example, I did a quick back of the envelope comparison against Singapore. Nigeria's rate for the lowest earners kick in at less than $1000 at a higher rate while Singapore has a far higher rate for its highest earners.

Nigerian policy makers thinking in terms of global competitiveness should have decided for example, that they want a far more market friendly and competitive personal tax rate than every emerging market nation, BRICS, G7, and G20. With how the Nigerian executive can arm twist the legislative to get what it wants, it could have gotten this.

5). On the corporate tax rate front, I think this is the lowest hanging fruit which Nigeria (and in fact the African continent) is not taking advantage of. I know the fashionable talking point is about "race to the bottom". But a country like Nigeria should go for an Irish style low corporate tax rate of at least 10% (maybe even 5% and 0% in some industries) and on top of that have a super deducting regime regime (say 250%) in which say the cost for setting up factories, deploying capital equipment are instantly written off immediately. I know all the fashionable international organizations would wail all day and night about Nigerians unfair tax practices and how 15% is a holy rate no one is allowed to go below - they should be ignored and politely told to get get lost.

For example, an aspect of the tax bill I actually liked but I felt could be far better was a schedule of industries which get VAT rebates etc. IMO, VAT rebate is deeply weak and mediocre. Fuse that schedule with an Irish style low tax rate and instant super deducting as I suggested and this could literally change Nigeria's economic fortunes forever. Furthermore, it probably would set off a domino on the African continent. I can see countries like say Kenya, Ghana and say Tanzania immediately moving to copy this when they see how it makes Nigerian very competitive overnight.

6). I've said something for a very long time and this bill only confirmed it. Nigeria lacks a privately funded think tanks that can for example analyze the recently passed tax bill and analyze it, score it and begin pointing out to the population where the dead bodies are in the bill.

For the most part people had to believe what the gentleman who shepherded the bill said. I'm not saying he lie or was dishonest in the goods he sold. But this is not how this game works.

7). Lastly, I don't hide my preference for a drastically smaller federal government. Tinubu claims to lean in such a direction - I've always had my misgivings about the coherence of his views in this regard - but he just signed a law which if it goes as advertised (that is, the central government consuming more of national output), such totally undercuts what he says in this regard or what he might try to do in this regard.

Nice one sir . Well researched and written. I have two comments . One for the main article . I will make the second one for the additional comment you made.

First Comment:

A. You asked if the new Tax Act is pro-poor ? Yes I believe it is . If we believe, the income per head in Nigeria has been dropping both in nominal and real terms , and this per capita income will not witness a leap, maybe a crawl going forward, then excluding low income earners from paying tax is a good move.

B. Your discussion on Tax Administration is apt. I sincerely hope the administration can pursue its goals and implement them, especially the digitisation and all related matters . The major spat I foresee may come from those MDAs who hitherto used to handle the revenue collection themselves but have now seen that taken away from their control.

C. The fiscal people , especially the National Assembly people need to read this paragraph on rebuilding the fiscal state. It is a whistle to pause and think. Essentially, if the fiscal authorities can take a look at different scenarios in future from now , they may be able to plan appropriately.

D. On the Taxation and Growth , this is nicely done and technically researched. I love the economics of taxation you brought into it, especially the idea of the Laffer Curve. Before this reform effort by Tinubu's administration, the duplicity/multiplicity of taxes were a menace. They are still but I believe as the reform dividends kick in, they will dissipate. Multiple taxes make things more expensive than they would normally be. Any attempt to erase them is welcome . Multiple taxes cloud both investment and financing decisions. Having rogue collectors or collecting system does not help broader public finance.

----

I will add my second comment below your additional notes.