The Detty December Arbitrage

Must all good things come to an end?

Early in November, the Financial Times published a story about an oil trader called Christopher Eppinger. The gist of it was that Eppinger, a 31 year old German, had managed to make $250 million for himself in the space of 30 months by trading $2 billion worth of oil. The piece explained the specific opportunity he had taken advantage of:

Following the 2022 invasion, western powers responded to Russian aggression with wide-ranging sanctions, and several of the world’s biggest traders, such as BP and Shell, quickly ceased all dealings with the country. Privately held commodity giants meanwhile pared back large parts of their business. Because oil was ultimately deemed too important to the global economy, the west eventually settled on a price cap designed to allow Russia to keep exporting while limiting the revenue it could earn. And so, a handful of risk-takers stepped in to profit from doing business that others were reluctant to touch.

The price cap proved especially helpful, Eppinger said. “It was a little bit of a black box” to begin with and then “I was sure I [could] do it in a legal structure”. Eppinger sipped on his Coke Zero. Had there been a complete embargo, as some traders had expected, then he would not have touched Russia at all. “Then I would’ve been a criminal.”

The core arbitrage was between “tainted” Russian-origin fuel oil that few Western players would touch and the continued strong demand and higher prices for compliant marine fuel and diesel from refineries and traders that wanted legal and reputational cover. Russian producers and associated middlemen had to offer large discounts because many oil majors and banks pulled back, and financing was scarce, meaning that oil could be bought cheaply, and on open credit.

At the same time, end buyers such as Uniper, Vitol, Raízen and others still needed product in places like Fujairah, Brazil and China and were willing to pay close to prevailing market prices provided they had documentation showing compliance with sanctions or non-Russian/blended origin. In other words, the classic arbitrage appeared - the same thing had two different prices and if anyone was smart and quick enough to bridge that price gap, they could pocket the difference for themselves.

Eppinger’s company, CE Energy, bought heavily discounted fuel oil and other products that were originally Russian but, by the time Eppinger took ownership in Fujairah tanks, carried certificates stating they had been blended in the UAE or otherwise no longer had Russian origin, which his lawyers treated as sufficient under the price-cap rules. He then resold this product down the chain (e.g. via Gulf Petrol Supplies to Uniper, and directly to Vitol and others) at much higher, near-market prices, capturing the spread created by sanctions-driven discounts, limited competition, open-credit from Russian-side suppliers, and buyers’ willingness to pay up for compliant oil.

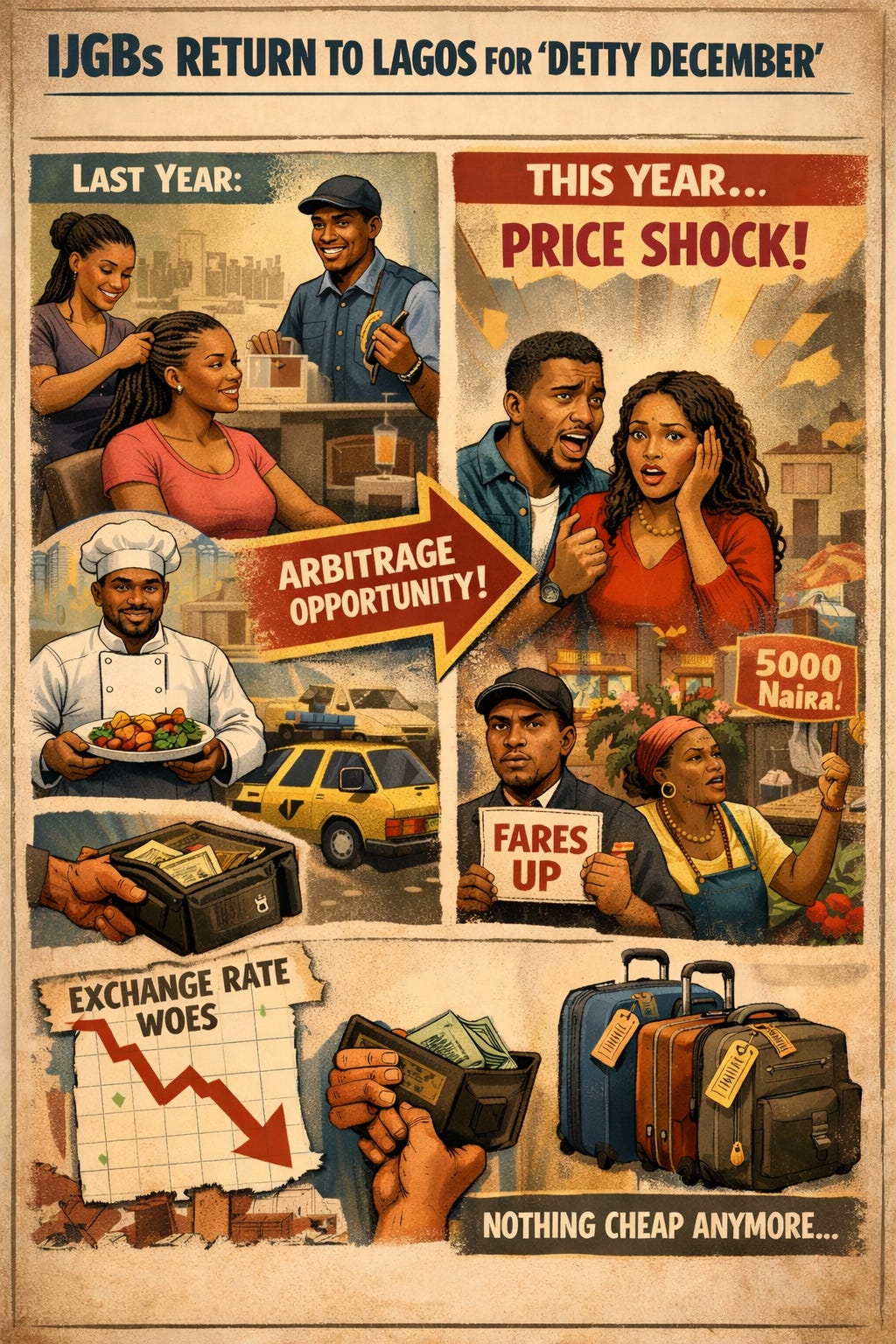

The Detty December Arbitrage

The explosion of diaspora returnees in December 2023 was impossible to miss, driven almost entirely by the Naira’s collapse after President Tinubu’s May inauguration. The message circulating back then was that Nigeria was on sale. A mere £100 converted to Naira allowed returnees to live like kings. ‘Detty December’ became less about culture and more about arbitrage - a window where the ‘IJGB’ set could procure leisure and luxury services - from nightlife to personal grooming - at a fraction of the cost required in the UK or US.

A year later in December 2024, you could still see and hear stories about this arbitrage opportunity. Here for example is a story from New Lines Magazine from a year ago:

Finding a stylist in the U.S. who was well-schooled in hair braiding was challenging enough; finding one who could undertake celebration-ready, knee-length braids and not break the bank was nigh on impossible. But not in Lagos.

Asimobi’s tailor recommended a salon near her hotel — a sleek, upscale place with long mirrors, soft seats, complimentary drinks and snacks, and a veritable army of nimble-fingered stylists who crowded around to coif her to perfection in about four hours. The bill? Just 32,000 naira ($21). Even with a 6,000 naira tip, a hairstyle that would have cost hundreds in the U.S. rang up to about $25. So of course, Asimobi made a TikTok about it.

She’s not the only one. Hundreds of videos have cropped up on the platform showing tourists lounging in salon chairs, sipping a drink and scrolling away as a team of braiders tackles the task of bringing their celebration ’dos to life — all while the tourists brag about the relatively affordable price. But as more and more diaspora Nigerians come for Detty December and spread the word on social media about the services they’re getting for a steal, stylists have begun raising prices for the high season, and locals are being priced out of the salon chair.

Naturally, this economic distortion came at a cost. As the diaspora bid up prices, they created an inflationary pressure that alienated residents earning in Naira, effectively pricing them out of their own city. I witnessed the aftermath firsthand during a visit in January, once the Detty December frenzy had subsided. Seeking to satisfy a craving for amala, I was directed to a place called Nest in Victoria Island. After enduring the requisite Lagos traffic, I arrived only to find the establishment was closed for what they claimed was “deep cleaning.” While waiting for a taxi, I asked a staff member about their December. Her face lit up with a knowing smile - business had been excellent. The subtext was that the seasonal spike allowed them to compress months of profit into mere weeks. The result was exclusion for the locals and a degradation of standards; having secured their windfall, the business felt comfortable arbitrarily shutting down for a day.

End of Arbitrage

Eppinger’s arbitrage effectively ended when US sanctions policy shifted to explicitly target Dubai-based intermediaries trading Russian oil at any price, which broke the open-credit, low-competition conditions that had made the trades so profitable. He halted all Russian-related trading after US president Joe Biden’s administration imposed sanctions on several Dubai-based traders involved in Russian oil, meaning that even price-cap-compliant deals could now trigger penalties. This new enforcement stance made the legal and political risk too unpredictable for him and his lawyers, closing off the “black box” space in which documentation and price-cap compliance had previously been enough to operate.

Those sanctions and the increased scrutiny meant Russian-side suppliers were no longer willing or able to extend the generous open-credit terms that had allowed a tiny firm like CE Energy to intermediate billions in cargo with minimal capital. Once that cheap-credit, high-discount, low-competition environment disappeared, the spread he was capturing shrank and the risk-return profile flipped, so he shut the Russian book and pivoted to seeking bank financing for non-Russian trading.

This year the unmistakeable message from Detty December pilgrims is that arbitrage opportunity is over. Social media is awash with stories of “greed” causing prices to spike completely out of sync with reality. The beauty influencer Laura Ikeji claimed that the braids she had done for N70,000 just before Detty December officially opened was now getting quoted at N200,000. Perhaps the most egregious is people having the bookings they made earlier in the year cancelled so the suppliers could resell them at much higher rates.

Ultimately, we can view this as the straightforward conclusion of an arbitrage play. If braiding hair costs ₦50,000 in one market and ₦200,000 in another, the influx of travellers seeking to exploit that ₦150,000 spread sends a clear signal. Local vendors, realising they have been underpricing their labour, naturally move to capture as much of that ₦150,000 surplus as possible. In time, prices converge to the point where the trip is no longer economically rational, and the Eppingers of hair braiding are forced to seek their bargains elsewhere.

But is that all?

Yet in Nigeria, straightforward explanations rarely suffice. A recurring pattern emerges instead: any new opportunity, however promising, quickly collapses into a frenzy that ensures its own demise. From Detty December to fresh immigration pathways (Nigeria remains the only African country barred from the US Visa Lottery after rapidly exhausting its allocation), the same dynamic takes hold - a collective conviction that whatever is available today will vanish tomorrow, triggering a rush to claim as much as possible, as quickly as possible. And in a nation of 200 million people, even a modest proportion engaging in any activity translates into staggering absolute numbers.

This same dynamic can be seen in some of the mindless corruption cases that capture the public imagination. Someone put in custody of public funds proceeds to help themselves to as much of it as possible with the remorseless logic that this is their one opportunity to never ever be poor again.

The defining feature of a poor country is of course that there is simply never enough of anything. There are not enough houses, not enough roads, not enough hospitals and, in the case of Nigeria, not enough food. Once can see all of this in the airport queues and maddening traffic in Lagos as everyone tries to be outside at the same time. All of which end up reinforcing the self-defeating feeling that maybe nothing good can last for very long around here.

Is this all a bit too much philosophising over Detty December? Perhaps, but this was one of Nigeria’s first export products in a very long time where the vast majority of value could be captured domestically - to partake, you had to physically be in the country, meaning a real boost for local businesses. If we have witnessed its peak this year, that will have real economic costs. I am reminded of the Yoruba aphorism that if you’re not going to eat something, the last thing you should do is take it anywhere near your nose. Detty December pilgrims may come armed with “hard currency,” but they also save for practically the whole year to be able to unwind in Nigeria in December. If in just two years prices have ratcheted up to the point where making the trip is no longer affordable, then is it better to have not loved at all than to have loved and lost?

New Equilibrium

Detty December will of course not die. The other way to think about this is that the bubble might burst and things settle at a new equilibrium. People will still go back to Nigeria for a jolly in December. There will still be concerts and parties to attend and friends and families to fellowship with. And one can easily fall into the temptation of extending what is mainly a Lagos phenomenon to a Nigeria wide one - what is Detty December to a man in Yobe or Benue? For the vast majority of Nigerians, life goes on as normal.

We are left, however, to wrestle with a stubborn question: why is international price competitiveness so elusive for Nigeria? Why can the nation not cultivate a sustainable edge that outlasts a fleeting boom? The fact that Nigerian oil costs significantly more to extract than that of its global peers is a telling indictment. These questions strike at the very heart of the country’s economic viability. In a hyper-connected world where technological advancement ensures no nation holds a permanent monopoly on natural resources, the inability to compete on efficiency is a strategy for irrelevance.

If the Detty December arbitrage is over, it is because the country has once again priced itself out of a unique opportunity.

One thing that could help is spreading out the supply, though this presents a serious security challenge. Many diasporans of eastern origin would prefer to spend December closer to home, but that would involve significant security costs. As a result, most would rather stay in Lagos and have their families fly (or bus) in to join them for the holidays.

If insecurity and bad roads were not such major obstacles, supply would naturally spread to cities like Enugu, Owerri, Port Harcourt, Calabar, and Uyo.

I was a Detty December skeptic, so much so that when I got a chance to take time off to visit Naija this year, after being away for over a decade, I sacrificed Thanksgiving holiday to avoid that busy December visit.

But mahn, Lagos close to December was fun and businesses are making a killing. I’d so much hate for them to lose that to disorganized greed. One example, we rented a car, it was advertised as a 2023 model. What we got was a battered 2016 interior inside a shiny 2023 body? Who does that?? AC was shitty, the air filter did zero against Lagos fumes. Got them to replace twice with little improvement. The thing cost the same as renting from Avis. Kmt!

It came with a driver sha who claimed he’s paid what I calculated as close to 15% of our cost. So much of that profit isn’t going to labor, which remains very cheap in Nigeria. I hope they don’t ruin a good thing.