One Person's Job

Nigeria has a choice to make on manufacturing strategy

Another day, another story of a multinational company exiting Nigeria after initially being lured by the prospect of riches to be made from selling its products to millions of Nigerians. This time it is the Huggies diaper maker, Kimberley Clark:

Diaper and sanitary pad manufacturer, Kimberley Clark will soon announce an imminent shutdown of its Ikorodu production facility two years after investing $100 million in Nigeria.

Sources within the company informed Nairametrics that the plant has been producing below capacity from late 2023 into 2024 due to the harsh economic environment within the country.

Just two years ago, it opened a $100 million factory in Lagos to much fanfare with the promise that it would create thousands of jobs and sell cheap(er) diapers to Nigerians:

A US company, with the aid of the United States Embassy and Consulate in Nigeria, has launched a $100 million state-of-the-art diaper manufacturing facility in Ikorodu, Lagos.

The new facility is Kimberly Clark’s, an American brand headquartered in Texas, the United States with operations across many countries.

According to the company in its press release seen by Nairametrics, the facility has the capacity to create over 1,000 direct and 5,000 indirect jobs with the potential to scale over the next 3-5 years of operation.

Anyone will be by now familiar with the way the ‘debates’ around these announced exits go. In general, most Nigerians are uneasy about it since it’s hard to put a positive spin on someone giving up on the country after spending millions of dollars just to get in. So the ‘debates’ take another turn which allows people to be split down the line on the matter. People you might call ‘Nigerian Nationalists’ insist that the exits tell you more about the exiting company’s failures than anything substantial about the Nigerian economy itself. In that sense, they can always point to competitors of the exiting company and how the upstarts have systemically eaten the exiting company’s market share over the years, forcing their inevitable departure.

Maybe their argument is the smoke pointing to the existence of a nearby fire. But it misses what I think is the wider picture which is that increasingly, manufacturing for the Nigerian market is ‘one person’s job’.

In the case of diapers, that one person is now the Turkish company, Hayat Kimya:

Hayat Kimya is one of the two key businesses within the Hayat Holding portfolio, a company first started as a wholesale fabric business in Turkey in the 1930s, around the time when Turkey was beginning to industrialize. In 1967, the business started manufacturing fabrics, and in 1969, it launched the Kastamonu integrated chipboard plant. In 1987, Hayat Kimya, the business and name that is more familiar to most of us today, was founded to target fast moving consumer goods markets. Today, the company makes products in the hygiene, tissue and home care categories offering well established brands such as Bingo (laundry and home care), Molfix (baby diapers), Molped (feminine care), Papia, Familia, Focus & Teno (cleansing tissue), and Joly and Evony (adult diapers). In the baby diaper category, Hayat Kimya is ranked number five globally.

[…]

In an interview, Ibrahim Guler, vice president of operations at Hayat Kimya, explains that apart from being the market leader in Turkey, Algeria, Cameroon, Madagascar, and Nigeria, Molfix also ranks second in Egypt and Morocco. In Kenya, the company rose to the third place 18 months after entering the market. With the Papia and Familia brands in the sanitary tissue category, Hayat is the market leader in Turkey, Bulgaria, and Russia. The company firmly protects its second place position in Iran with its Papia and Teno brands. Hayat is the second in the market with its Test brand, which they have positioned exclusively for the Algerian market, and has taken the second spot in the same market with its Bingo brand, which is positioned in the premium class. In Bulgaria, Hayat is the leader in the fabric softener category.

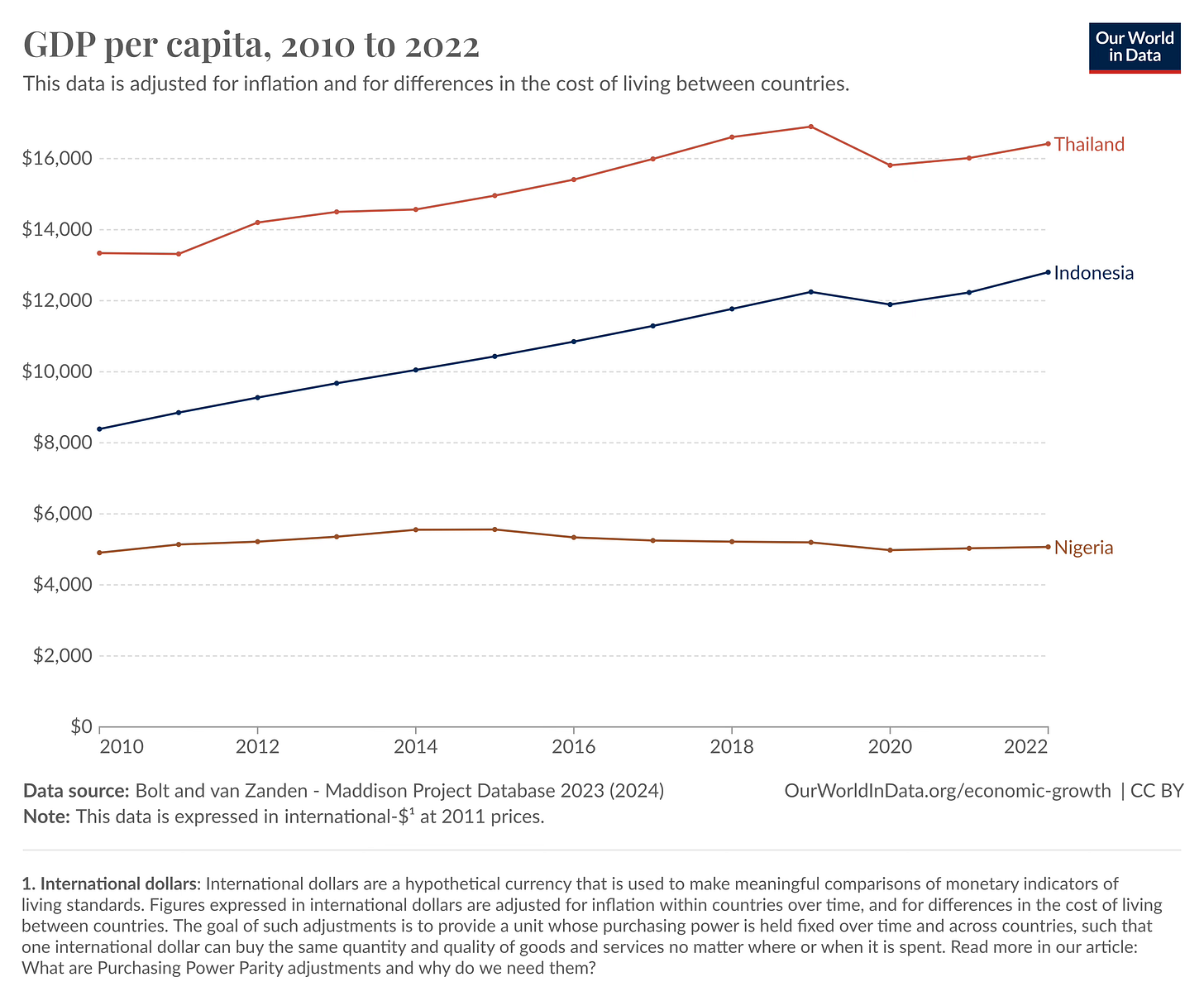

This is all to say that any manufacturing strategy that is predicated on manufacturing for the Nigerian market alone is likely to run into big trouble in short order. Yes, there are 200 million Nigerians in the country but the vast majority of them are unable to afford anything that is not food (and even that is a big struggle). Nigeria is now in a decade of practically zero growth which really means that Nigerians are getting poorer when you factor in population growth:

Trying to sell any kind of consumer product into such a market means there can only ever be one winner. You are not going to get the kind of market segmentation where one manufacturer sells premium diapers to the rich and middle class while another focuses on poor(er) people by selling them cheaper products. Steady economic growth would mean that there is a constant stream of people moving up from poor to middle class and changing the product they buy. In that scenario, both manufacturers can be sustained in the market for a very long time.

With no economic growth, the consumer’s march is always to the cheaper products and anyone selling above that price is living on borrowed time. The promised new middle class are simply not coming. It makes no sense for two people to do One Person’s Job so the guy selling at the higher price point has to leave.

The solution to this is the boring point we constantly repeat here at 1914 Reader. Here is what car manufacturing looks like in Mexico:

Mexico is the world’s seventh-largest passenger vehicle manufacturer, producing 3.5 million vehicles annually. Eighty-eight percent of vehicles produced in Mexico are exported, with 76 percent destined for the United States. Established automakers in Mexico include Audi, BMW, Ford Motor Company, General Motors, Honda, Hyundai, Jac by Giant Motors, Kia, Mazda, Mercedes Benz, Nissan, Stellantis, Toyota, Volkswagen, and Tesla, which recently announced a new plant to be built in the state of Nuevo Leon as part of its electric vehicle production.

Mexico is the world’s fifth-largest manufacturer of heavy-duty vehicles for cargo, hosting 14 manufacturers and assemblers of buses, trucks, and tractor trucks, and two manufacturers of engines. These producers have 11 manufacturing plants that support more than 28,000 jobs nationwide. Mexico is the leading global exporter of tractor trucks, 95.1 percent of which are destined for the United States. Mexico is also the fourth-largest exporter of heavy-duty vehicles for cargo and the second-largest export market after Canada for U.S. medium and heavy-duty trucks. Top players include Cummins, Detroit Diesel Allison, Freightliner-Daimler, Kenworth Mexicana, Mack Trucks de México, International-Navistar, Dina, Scania, Volvo, VW, Man Truck & Bus, Mercedes-Benz, Hino Motors, and Isuzu Motors.

Sure, it helps that Mexico is next door to the world’s largest consumer market but the larger point is that is a car manufacturing strategy based on serving the Mexican market alone would yield a fraction of the jobs and cars above.

Nigeria has a choice to make - encourage manufacturing for the domestic market and live with the result of that choice or make a play for manufacturing for exports. These two things are not the same and they require different strategies. As the result of studies across Africa have shown:

Firms started out as exporters or nonexporters, and very few firms shifted to exporter status from serving the domestic market.

Made in Africa: Learning to Compete in Industry (Carol Newman et al)

A strategy to manufacture for exports has knock on effects on electricity, transport and various other policies. If Cambodia can export goods worth more $20bn a year, there is nothing to suggest Nigeria cannot export a lot more than it currently does (outside of crude oil).

Remember all this when the inevitable debates start once again about how Kimberley Clark left Nigeria because it didn’t know what it was doing and as such it allowed some upstart to drive it out of the market.

The reply to such arguments should simply be - why can’t there be two diaper manufacturers in a country the size of Nigeria?