Does Sport Matter?

Why Nigeria should aim to be a sports power

The UK Times has this paragraph as a summary of Nigeria’s participation in the Paris 2024 Olympics:

Nigeria failed to come away with any medals at Paris 2024, despite having 88 athletes there. That was the largest contingent by a country at this Olympics that didn’t manage to win a medal. Eighty-eight was the most representatives they’ve sent to a summer Olympics, so the world’s sixth largest nation by population will be disappointed with their return.

The best that can be said is that Nigeria had a very embarrassing olympics. Unlike in previous editions where the medal count was low (or non existent), this one did not seem to have any redeeming feature whatsoever. It was one embarrassment after the other with Favour Ofili not being registered for the 100 metres (and all officials managing to dodge responsibility for the fiasco) or the cyclist Ese Ukpeseraye borrowing a bike from the Germans to compete in her cycling race. By the time Tobi Amusan - the country’s one true medal hope - started slowly in her 110m hurdles heat and failed to make the final, it felt as if the country’s perennial attempt to ‘wing it’ without much preparation had finally caught up with her. The Sports Minister became an emergency blogger on Twitter typing out a long jeremiad everyday.

Inevitably there has been a lot of soul searching going on with people wanting a root and branch reform of Nigerian sports to prevent this kind of embarrassment happening in Los Angeles 2028. But given where Nigeria is at the moment, buffeted by generational economic challenges and serious governance problems everywhere you turn, a pragmatic question to ask might be - is sports really that important right now? Does it deserve more government bandwidth at a time when the oil industry is suffering chronic lack of investment and inflation just won’t come down from painful highs?

Sports is easier than everything else

My answer to this question is yes, Nigerian sports is worth the effort to fix it. For the rather simple reason that sports is a lot easier than everything else Nigeria needs to do to become a socio-economically developed country. Sports are a valid pathway for young men and women in any reasonably developed country as it can harness their physical attributes in a way that rewards them mentally and of course, financially. In a country like Nigeria teeming with millions of young men and women struggling to find gainful employment, sport is a no-brainer.

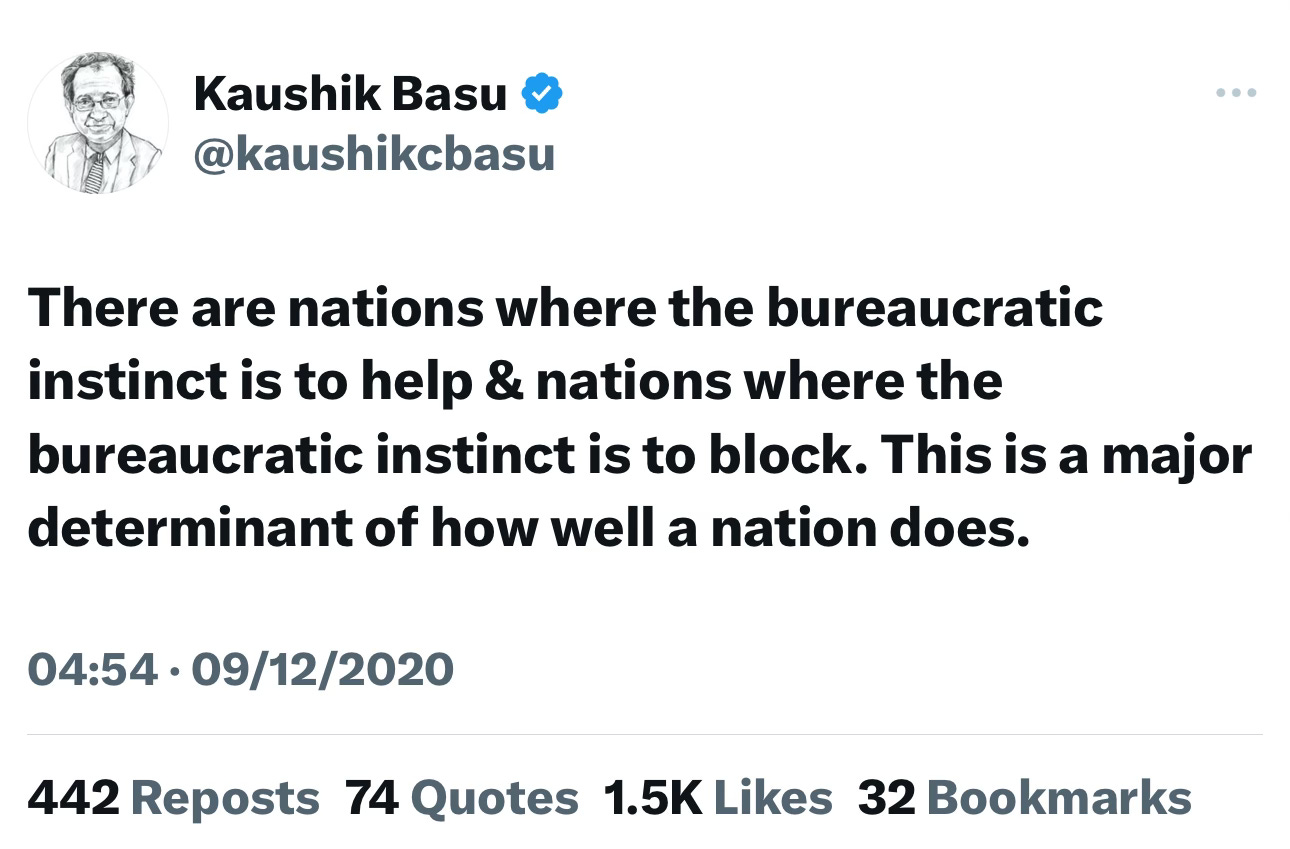

None of that is groundbreaking. The more important issue, from my point of view, is that it is the lowest hanging of all the fruits Nigeria needs to pluck. Here at 1914 Reader, we constantly harp on about how Nigeria needs to reorient its economy towards exports. But after decades (or centuries) of being a resource based economy, such a switch to exports would be an incredibly difficult task, even if a very necessary one. Transport and all other types of infrastructure will need to change as well as moving from a ‘blocking’ to a facilitation mentality, a big culture shift. ‘Unlocking’ sports is far easier compared to this.

How about Nigeria’s oil industry which is now facing an existential crisis after decades of systematic underinvestment as the golden goose was stripped of all available meat? If you were to mobilise say $30 billion of investments into Nigeria’s oil industry today, it may yield an additional 1 million barrels of oil per day in a decade’s time, all else being equal. A tiny fraction of that amount invested in sports will yield tangible results by the next Olympics in 2028.

Shanko’s example

Consider the story of Tobi Amusan. Quite literally out of nowhere in 2022, she became a global sensation when she broke the 100 metres hurdles record at the World Athletics Championships in Oregon. Later that year, the UK Times did a feature on her which highlighted her athletics start in Nigeria as well as the coaches who nurtured her:

“I knew she was going to do very well,” said Ayodele Solaja, founder of Buka Tigers athletics club in Ijebu Ode, the southern trading town where Amusan grew up, of the schoolgirl he remembers. “I knew she could be on the podium and get gold, but not a world record.”

The path to outdo her coach’s expectations was not straightforward. “She had a weakness,” Solaja said. “She was very small.”

Amusan is still only 5ft 1in, diminutive for any athlete. As a teenager, her nickname was Shanko, meaning “tiny” or “minute” in her native Yoruba. Detractors told her she would never make it. But she was “very determined”.

“She was very jovial,” Solaja said. “At that time she was one of my favourite athletes. I was always carrying her everywhere.”

But the more eye-catching part of the story was about Solaja himself:

Solaja, a former amateur decathlete who has trained several Nigerian Olympians but said he still works as a motorbike taxi driver to sustain his club, taught Amusan the combined events, which he did with all youngsters, recollecting that she was good on field as well as track, including at shot put and long jump.

All the man has is an eye for talent (by virtue of being an ex-athlete himself) and obvious passion for the work. It could not have been that financially rewarding if he had to supplement his income through Okada riding. Compared with building out energy supply and connecting millions of Nigerians and making sure they pay for the power they use, it is trivially easy to sustainably build a structure to replicate what people like Solaja are currently doing on their own wind.

No matter how difficult a place Nigeria is, no one can seriously argue the raw talent for football, athletics, swimming and all sorts of other sports is not there. The challenge is to build a structure to reliably identify that talent, put them in an environment that harnesses those talents and finally puts them on a platform to excel outside of Nigeria when they compete with their peers from other countries across the world. None of this is easy but relative to turning around the fortunes of the oil industry, it is a lot easier. And it will employ more people and do far more to repair Nigeria’s image in the world right now from the absolute battering it has been taking from online romance scams and assorted other negatives now inextricably linked to the country’s name.

None of this means that the country should give up fighting inflation or rebuilding its infrastructure for an export focused future for the sake of developing sports. The point is that while trying to reorient an economy towards exports and investing in the oil industry will be extremely challenging to do at the same time, developing sports can be done alongside any other priorities. It takes a bit of seriousness (also needed for everything else), vision (needed for everything else) and funding (needed for everything else).

But sports has a far greater galvanising effect on the country and will generate happiness and pride that an extra million barrels of crude coming out of the ground can never bring. Sport matters.

Why not be serious about it?

I really enjoyed this. Thanks for your excellent insights as usual. I don’t know the answer to why the country isn’t serious about sports, but I think the generational shift in the late 90’s when a large share of school enrollment shifted from public funded schools to private ones is a huge part of our sports performance issue.

According to Statista, from a 2019 data, 47% of elementary schools in Naija are now private, it’s 63% for secondary schools! In Tebogo’s Botswana, the data is 87% attending state owned public schools combined, with 10% private. So maybe there’s something there?

I was not a student athlete by any measure. However, I remember our school sports culture in 80’s and 90’s Naija was engaging, competitive and very intentional. Watching these Olympics with my young kids brought back a lot of forgotten memories. I forgot I knew the basic form for a Javelin throw, the triple jump rules and how to properly throw a shot put, ( the field one, not the other one 😃) even if I can’t throw beyond my shadow.

Most of us learned these things in mandatory PE classes, and on large, dedicated public school facility grounds built with youth sports in mind. Not to mention the all important public school inter-house sports festivals we all grew up with.

I’ve not lived in Nigeria in over a decade, but in my visits and interactions with the last few generation of Nigerian school kids, you can tell they’ve been shortchanged by their private schools - sports wise. PE is not prioritized and most don’t have the facilities or space for field sports.

I’m not shading private schools. They jumped in to fill a gap created by poor planning, teacher strikes and horrible years of public education investment. There is only so much a “school proprietor” can do with private investment. Most of the private schools I saw can barely fit a baby swing in their tiny concrete compounds. They are focused on getting their kids ready to pass WAEC, GCE or SAT. So they are likely thinking ‘who shotput help?’

Anyway, I’ve rambled enough. Nigeria can fix it, but like you said, it will take the same sense of purpose and vision required to fix our oil wahala or just about anything.

THe approach to fixing this for me seems to be a focus on school sports infrastructure. Reading this article (https://www.si.com/college/stanford/olympic-sports/stanford-athletes-win-a-school-record-39-medals-in-paris-games-01j51rgyctwv) about Stanford's performance at the olympics made this clearer. Also, concerning the Nigerian export economy, many of the Stanford athletes represented other countries that weren't the US. Most of these students paid hefty school fees or received scholarships to go to Stanford. Another notable university was LSU where Duplantis and Shacarri Richardson went to school.

I strongly believe we can improve attendance records and student engagement if we create a pathway in schools at all levels for sports inclined students. In Nigeria, the refrain too often is that sports are useless compared to traditional professions. And the stories of people like Solaja make this statement seem true. But we have seen sports empower people in other countries, it's up to us to replicate this.