Capitalism In The Colonies: African Merchants in Lagos, 1851 - 1931 [Chapters 3 - 4]

Some Very Big Men make their appearance

Unusual Stories

The story continues. In the previous post, I talked about how a rupture in the business landscape - from slave to palm oil trading - brought with it an immense destruction of wealth. That is to say, most of the wealthy slave traders did not end up becoming wealthy palm oil traders. But there was one exception to this - Oshodi Tapa.

His story is generally well known but is worth summarising here. He began his life as a slave and later on graduated into slave trading. Originally named Landuji, he came to be known as Tapa, the somewhat derogatory name Yorubas called (and still do) people from the Nupe country in Nigeria’s middle belt. He would later on obtain the title of Oshodi which then became his family name. He arrived in Lagos in the 1820s as a slave of the the Oba Osinlokun who evidently saw something special in him. Osinlokun sent him to Brazil to learn the Portuguese language (presumably to help his business) and after Osinlokun’s death, Oshodi was savvy enough to attach himself to his successor Ojulari and after that Ojulari’s brother, Kosoko. He ran a lot of business for Kosoko who then took advantage of his Portuguese language skills by sending him off to Brazil to encourage the return of some slaves.

Oshodi was a brilliant man, described in 1854 by a British naval officer as having ‘more than ordinary sagacity.’ Having picked up English somewhere along the line, he became valuable to the emerging British authorities and was one of the earliest pioneers of palm oil trading in the 1840s, even while still dealing in slaves. One of his slaves, Momadu Awe, noted that Oshodi was the only Lagosian exporting palm oil before the Saros arrived. He cleverly repurposed his slave labor to produce palm oil, anticipating the shift away from the slave trade. Oshodi later became the key agent for O’Swald, a dominant German firm responsible for 44% of Lagos’s palm oil exports in 1855.

Oshodi eventually ran out of steam and by his death in 1868, his business was said to be ‘not so prosperous’ although he still owned many slaves and landed property. But his story is interesting in how rare and unique it was at the time of a businessman adapting to multiple political and business regimes and finding success in each one.

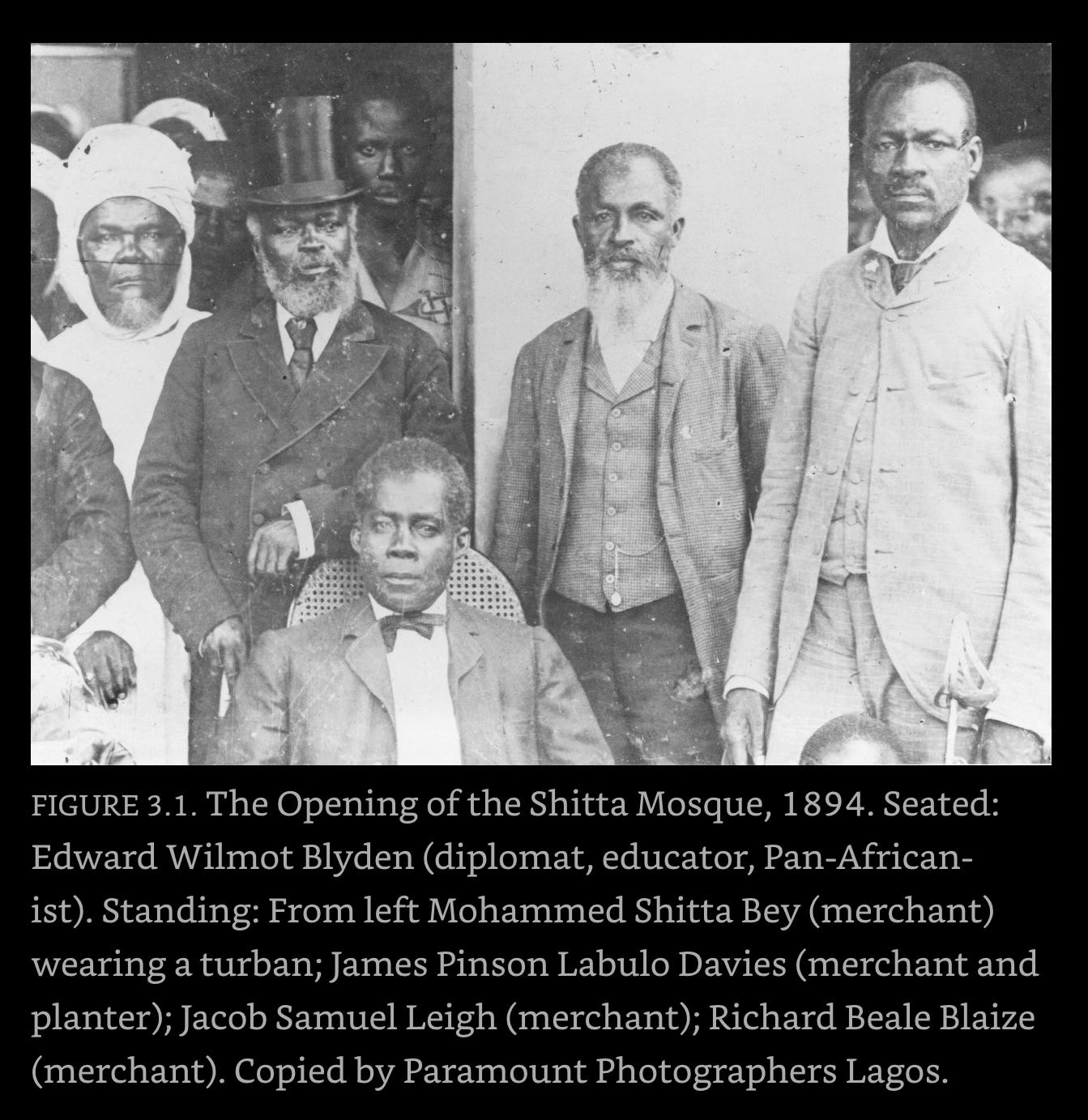

Another unusual story in Chapter 3 is that of Mohammed Shitta. Unusual in the sense that he bucked the trend of Saros as we generally knew them i.e. as Christians. He was born in Sierra Leone in 1824 to liberated slaves from Ilorin in Nigeria. As a result of the dominant Christian influence in Sierra Leone at the time, he was originally known as William perhaps until he returned to Lagos with his parents in 1844 whereupon he and his parents settled in Badagry where his father became the Imam of the Muslim community. After the death of his father in 1849, Mohammed Shitta moved to Lagos proper in 1853 (after it had become a British consulate) where he rose to become the richest and highest status muslim in Lagos. His business empire faced the north of Lagos where he had an advantage over the Saros in dealing with his fellow muslims as far as the Nupe empire and beyond.

Shitta did so well as a businessman that he retired on his own terms in 1889 and stayed put in Lagos. He was so wealthy that in 1884 he loaned a struggling French firm £7,200, a substantial amount of money which he could do without at the same time as he was building a grand mosque in Lagos which cost him up to £5,000 to complete. Abdullah Quilliam, the leading muslim in Britain attended the grand opening as a representative of the Sultan of Turkey who awarded Shitta the title of ‘Bey’.

The third and final unusual story is that of the George family. Charles was born to James a.k.a Osoba in Sierra Leone in 1840. The Saro line started from his grandfather Thomas a.k.a Masinka who had been freed as a slave earlier in the century and settled in Hastings, Sierra Leone. The family (Minus Charles) returned to Lagos in 1852 and James would go on to establish a large trading and shipping business spanning Lagos and Freetown. Charles joined the family in Lagos in 1862 and started running parts of his father’s business. In 1864, James and Charles formally registered a business - the first of its kind in Lagos - known as George & Son. James contributed £6,000 as capital while Charles chipped in £300 and they agreed to work together sharing profits and losses and to keep ‘perfect, just and true books of account’.

James always longed for a return to Abeokuta and he eventually moved there running the George & Sons branch while Charles stayed on in Lagos running their stores in Marina and Olowogbowo. They imported various goods including cotton textiles and exported palm oil and raw cotton (some of them produced by James’s slaves). After James died in 1876, Charles continued to run the business under the same name and remained wealthy until his own death in 1906 (he also disbanded his father’s slaves). He frequently travelled abroad and educated some of his children in England. Upon his death, he willed his business and property to his son, Charles Will George who ran the business until his own retirement in 1935 followed by his death in 1940. At this point the business had run out of steam and Charles Will was not known to be very wealthy upon his death.

These three stories are plot twists that disrupt the easy narratives we have come to believe about Nigeria. The slave who not only became a slave trader but also had the foresight to pivot into palm oil when the old game was up—hustling his way from tragedy to prosperity. The Saro who didn’t fit the standard mold, turning out to be a Muslim rather than the expected Christian. The family business that managed to cheat the odds and last for three generations, defying the ironclad rule that Nigerian wealth rarely survives more than a generation. These aren’t the usual stories we pull from the shelf when we think about Nigeria, and yet there they stand, waving at us from the margins. They don’t demolish the general truths we cling to, but they certainly complicate them, reminding us that while the broad strokes often hold, the finer details have a way of colouring outside the lines. It’s in these contradictions—the rogue data points that mock the trend lines—that we catch a glimpse of the fuller picture of Lagos and Nigeria.

Feyi

Making a "Big Man"

As noted in the previous review, the British bombardment of Lagos in 1851 ‘officially’ ended the slave trade. Some of the existing infrastructure of the now-forbidden business, like the barracoons for holding slaves, informal contracts, and other norms, proved insufficient for the transition to the legitimate commerce of palm oil trade. The new trade needed new ‘institutions’. With the formal annexation of Lagos in 1862, the merchant community had to find new ways to adapt to the new commercial environment. Two significant developments were the credit and property markets. The former was necessary for the expansion of trade. At the same time, the latter became a primary form of collateral for loans, fostering a booming real estate market that allowed traders to raise capital. These developments are themes that I promise to return to later (for example, the advent of the crown grants and its enhancement of freehold land tenure was an important legal innovation for the emergence of formal property rights and, thus, a booming property market). However, another critical development in the new Lagos commercial environment is the role of brokers.

Brokers played a central role in the Lagos commercial system, acting as intermediaries between European merchants, Saro traders, and the indigenous population. The networks they built allowed them to accumulate commodities like palm oil and distribute European goods. European and Saro traders dominated the commercial district along the Marina, where many large brick houses symbolized the growing wealth of these merchants. This area also became the focal point for political power, with traders and brokers exerting influence over the colonial government and local chiefs. European firms like Régis Ainé and Witt & Busch, along with prominent Saro figures, played pivotal roles in shaping the city's economic landscape. These men were involved in trade and local politics, using their influence to navigate between the colonial government and the indigenous leadership. The distinction between brokers and merchants was not always clear, as many brokers managed large networks of dependents and became politically influential figures in Lagos society. Providing a lens into the interplay of Lagos, the commercial city, and Lagos, the political city (as noted in my previous entry). One such broker was Chief Daniel Taiwo, whose life and career were detailed by Hopkins in Chapter 4.

Chief Taiwo was an illiterate former slave who became one of the most powerful merchants in Lagos. He rose through political and commercial ranks by aligning with British colonial authorities and building a wide-reaching network that included Saro merchants, European traders, and local chiefs. His ability to adapt to Lagos's changing political and commercial environment was critical to his success. His story begins with his early years in the slave trade, where he was part of Kosoko's (former Oba of Lagos and successful slave trader who was deposed by the British) inner circle. However, after the British bombardment of Lagos, Taiwo swiftly shifted from the illegal slave trade to legitimate commerce. He quickly adopted the new commercial practices introduced by the British, such as freehold tenure and the use of silver coinage.

Taiwo's rise to power was facilitated by his astute political machinations, which included aligning himself with powerful colonial figures like Governor Glover. His role as an intermediary between the colonial government and indigenous authorities was crucial to his success. He secured safe passage for traders, helped negotiate disputes, and leveraged his influence to open trade routes following the British conquest of Yorubaland in 1892. He was an excellent example of the thin line between business and political dealerships. He was a ‘big man’, not just in terms of wealth, but in his ability to engineer political relationships to his benefit. Letters from his contemporaries reveal that many people sought his help resolving debts and securing political favours, indicating his substantial clout in commerce and governance.

Chief Taiwo earned the title ‘head of all markets in the colony’ due to his extensive trading network from Lagos to the interior. He had branches in key market towns such as Abeokuta and employed agents across the region. Taiwo's business dealings included relationships with European firms and prominent Saro merchants, such as James Davies and Richard Blaize. He was a key player in regulating market activities and setting prices, particularly in the produce trade. Even in his later years, he was still able to remain influential despite challenges from many other local powerbrokers, and he remained adaptable to shifting political dynamics.

For contemporary Nigerian readers, Chief Taiwo's story is familiar. The economic and political landscape of the country today is still dominated by big men and the amount of influence they can wield. And even though the arena of action may have shifted to Abuja, as a current federal minister said recently, most of the decisions are still made in Lagos. Another important takeaway from this chapter is that wealth may be transient, but politics always survives. In our previous review, Feyi made a point about the pattern of wealth destruction in the country - what seems clear from Chief Taiwo's story is that the only path to the endurance of wealth in Nigeria is to be on the right side of politics - wherever that may be.

Tobi

I love these reviews as it leaves no doubt in my mind that the Saros are low-quality elites.

No, the traditional elites are already low-low-quality.

As ex-slaves, I do not expect much from the Saros. However, we can thank they and the British Missionaries for the spread of literacy. And that's about it.

The psychology of the Saros is survival either through wealth accumulation by any means necessary or politics or both. And they're actually well positioned to take these opportunities by virtue of their literacy and familiarity with the British system.

Their disposition towards Lagos, and Nigeria, is no different from their colonial masters' i.e. non-commital, extractive, no value-add. To make matters worse, the local traditional elites are no different. In fact, those are worse. Now, we're stuck in the perpetual dalliance of who gets a share of what between these two in the clown show we call politics. Sigh.