Big but not Mighty

A short note on the persistence of import substitution in Nigeria

In his latest piece, my co-blogger Feyi Fawehinmi wrote about the stubborn attachment to import substitution of policymaking in Nigeria. It needs to be said that the cult-like obsession with this status quo - which mainly just owed its existence to an irrational demonisation of anything 'foreign' - is a backwards-looking vision for the country that has not gotten us anywhere good and will not take us anywhere good. As Feyi argued, while often justified by a desire to boost local industries, how we have gone about import-substitution has only yielded a lack of competitiveness, inefficiencies, and misallocation of public and private resources. At a time in history when many countries prospered by integrating more with the global economy, Nigeria clung to the past and missed out on the party.

There is absolutely nothing new or unique about import substitution. Import substitution was the most prominent idea in development in Latin America and many parts of Asia after WW2. While it initially spurred domestic industries in these countries, the eventual results were bloated, inefficient, and uncompetitive zombies. It has also been convincingly shown that shifting to a more export-focused approach was one of the keys to the success of Asian economies over their Latin American peers. So why do successive governments in Nigeria remain clung to an old and discredited idea?

Surely, we can point to the fact that economic nationalism in the form of import substitution has been elevated to a national culture in Nigeria. Import substitution also enjoys strong consensus from the elites because it benefits them politically - many of whom are unwilling to tolerate the challenge to their power that will undoubtedly come from a prosperous economy and an expanding middle class. It is also true that import substitution is an important component of The Idea Trap that Nigeria has found itself in. The latter point deserves more attention, especially since its proponents think the current mood of the global economy, with increasing economic balkanisation, strengthens their case. A very common argument that is often repeated is that Nigeria has a huge domestic market, hence it has very little need for imports and even exports.

Is domestic demand enough?

The question of whether an economy can rely on domestic demand for development was the subject of a recent paper by economists Pinelopi Goldberg and Tristan Reed. They identified that a demand-side approach to development is constrained by the size of the domestic market. For one, to be productive and profitable, firms need to adopt technologies that have increasing returns to scale - and domestic market demand needs to be big enough to justify the fixed costs of these technological adoptions.

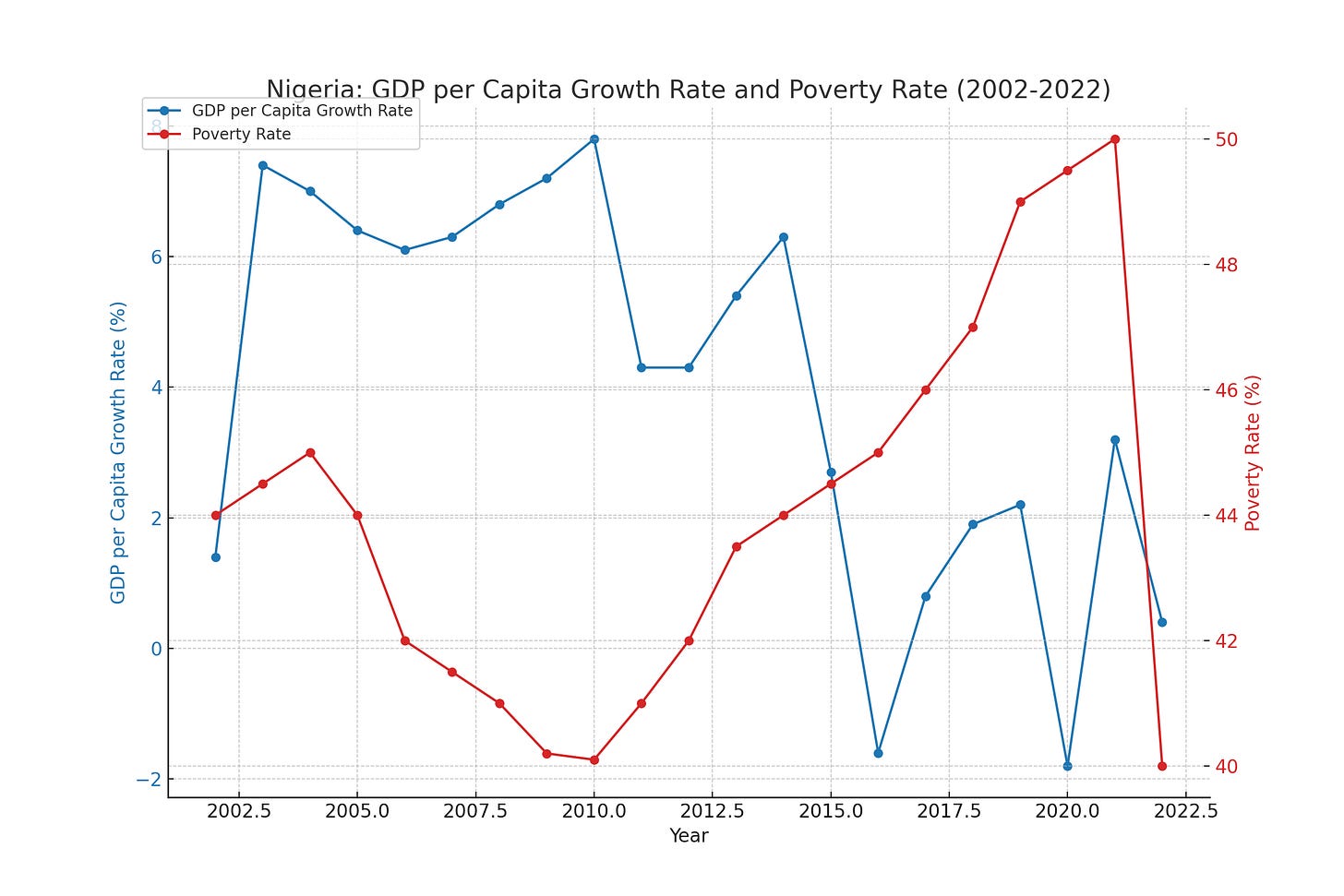

Investment by firms that fail to adequately gauge the size of the domestic market will most likely end up as a severe misallocation of resources. One implication here is that firms in lower-income countries need demand from overseas markets and better international integration to be efficient and productive at the very early stage of development. However, the most important point of the paper is how to gauge the size of domestic markets. It is quite common to see people assume Nigeria to be a 200 million people market, and imagine how profitable it will be to sell to that market. But Goldberg and Reed showed that sustained poverty reduction, the size of the middle class, income inequality, and robust economic growth are important determinants of the size of domestic markets.

Poor populations have limited purchasing power, which significantly constrains their ability to drive domestic demand. The World Bank estimates that low-income households in Nigeria spend over 60% of their income on necessities such as food, housing, and utilities, leaving little for discretionary spending that can stimulate broader economic growth. This limited spending capacity is insufficient to justify the adoption of advanced, increasing returns-to-scale technologies necessary for economic transformation.

The huge domestic market argument as a justification for import substitution in Nigeria is weak. Even though it is still a very popular argument with many influential people, and may partially explain the persistence of the cult of import substitution. Nigeria has never enjoyed a long enough period of prosperity to be able to rely on its domestic market for further development. Getting there will require playing an important part in the global economy.

In my next essay, I will review another paper that possibly explains why growth in Nigeria has been inconsistent. I will also discuss a viable alternative to import substitution.