Stranger Things - Nigerian Edition

How does one process the fact that a country's banking industry is openly betting against its currency?

We are in what is known as reporting season. This is when banks and other big companies report their numbers for the first 6 months of the year. I crave your indulgence to share something rather interesting and strange thing that is common across the accounts of the big banks. For this analysis, we will use just 4 banks - Zenith, GT, UBA and Access.

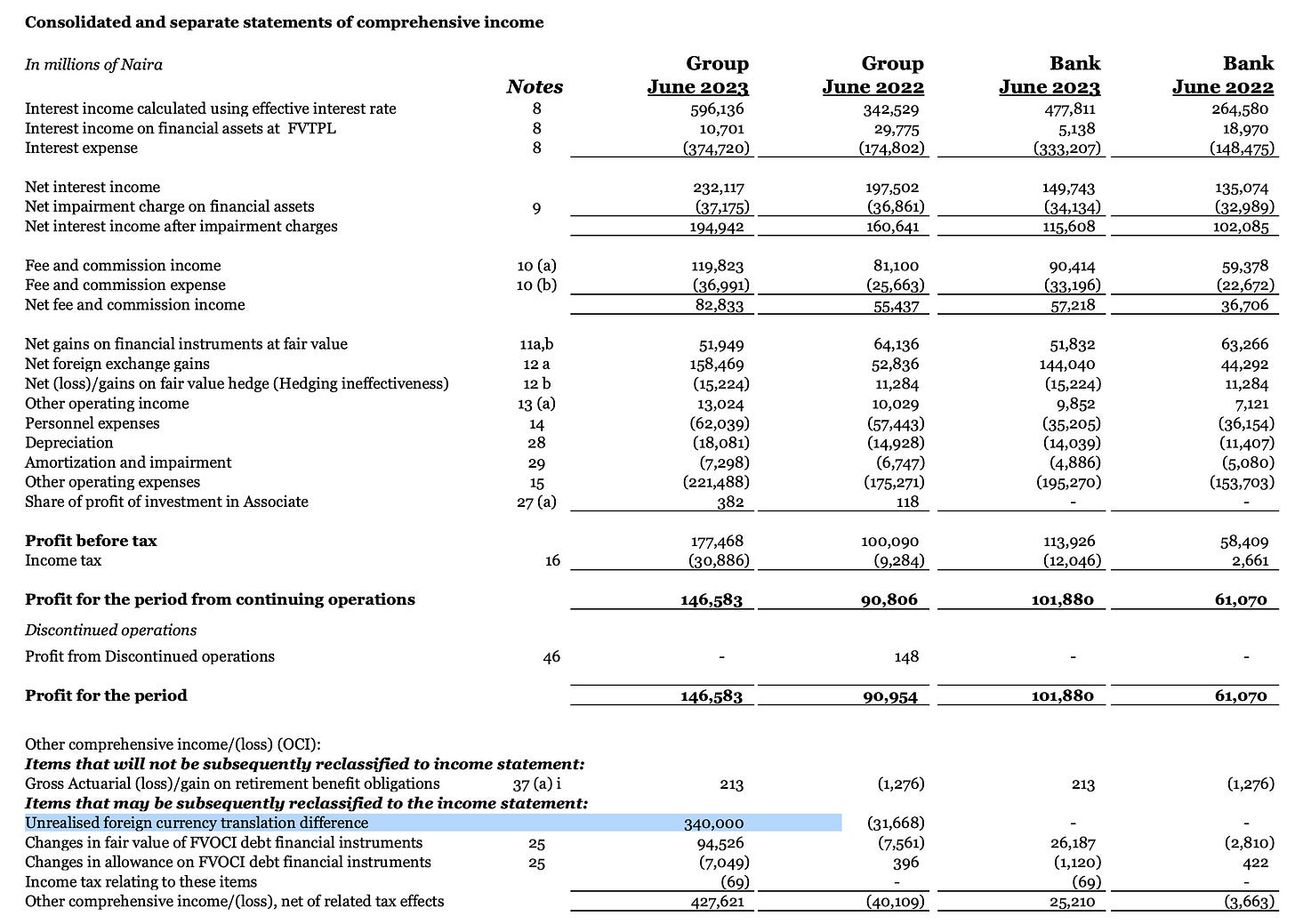

Let’s start with Access Bank:

The highlighted line is the bank recording N340 billion in foreign currency gains in the first 6 months of the year. To prepare the accounts up to the end of June 2023, the bank used an exchange rate of N756 to $1. So that N340 billion translates into a nice $450 million gain.

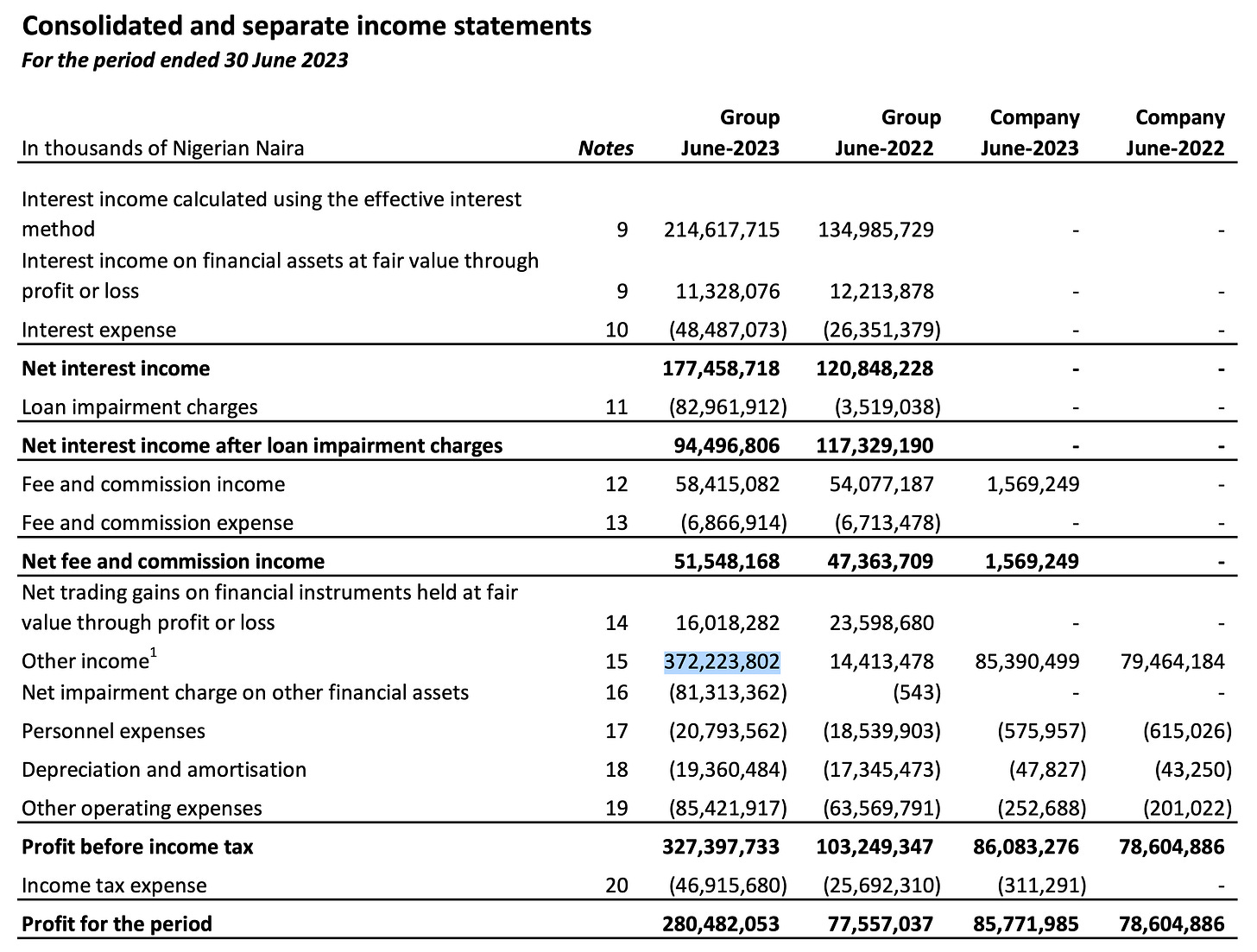

Moving on to GTBank:

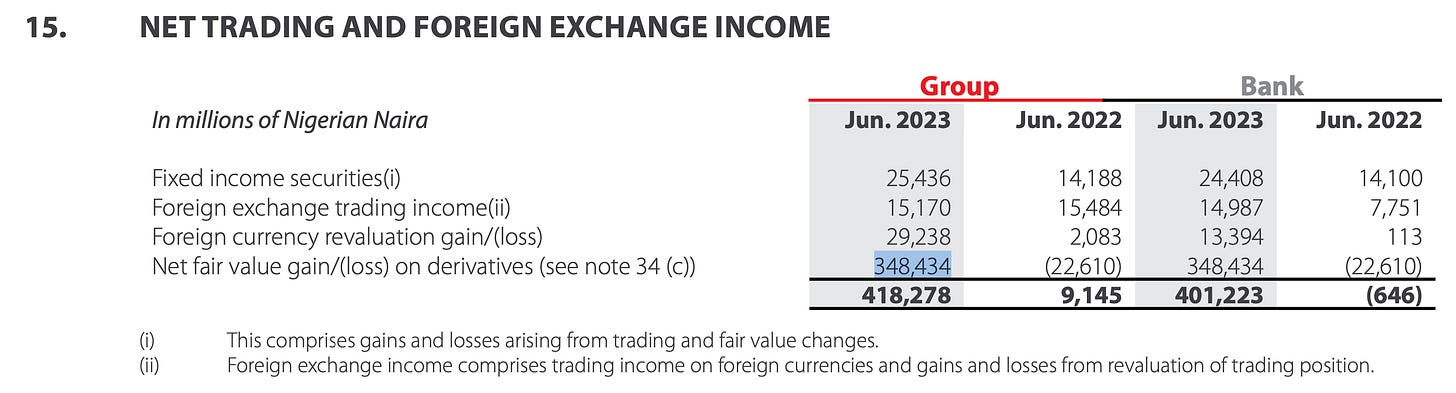

In their case, we have to jump through a couple of steps to get to what is inside the N372 billion figure that interests us. They say it’s in Note 15, so off to Note 15 we go:

The bulk of it is made up of unrealised foreign exchange gains, just as with Access Bank. Let’s call that a round $470 million and move on.

Up next is Zenith Bank:

Once again, the number that interests us here is the N368 billion and to get inside it, we have to jump to Note 11:

We see the bulk of that amount is down to the N355 billion of foreign currency revaluation gains, very similar to the other two banks. They used the same exchange rate as Access so that’s a cool $470 million.

Between just 3 banks, we are now well over a billion dollars of gains recorded for the first 6 months of the year.

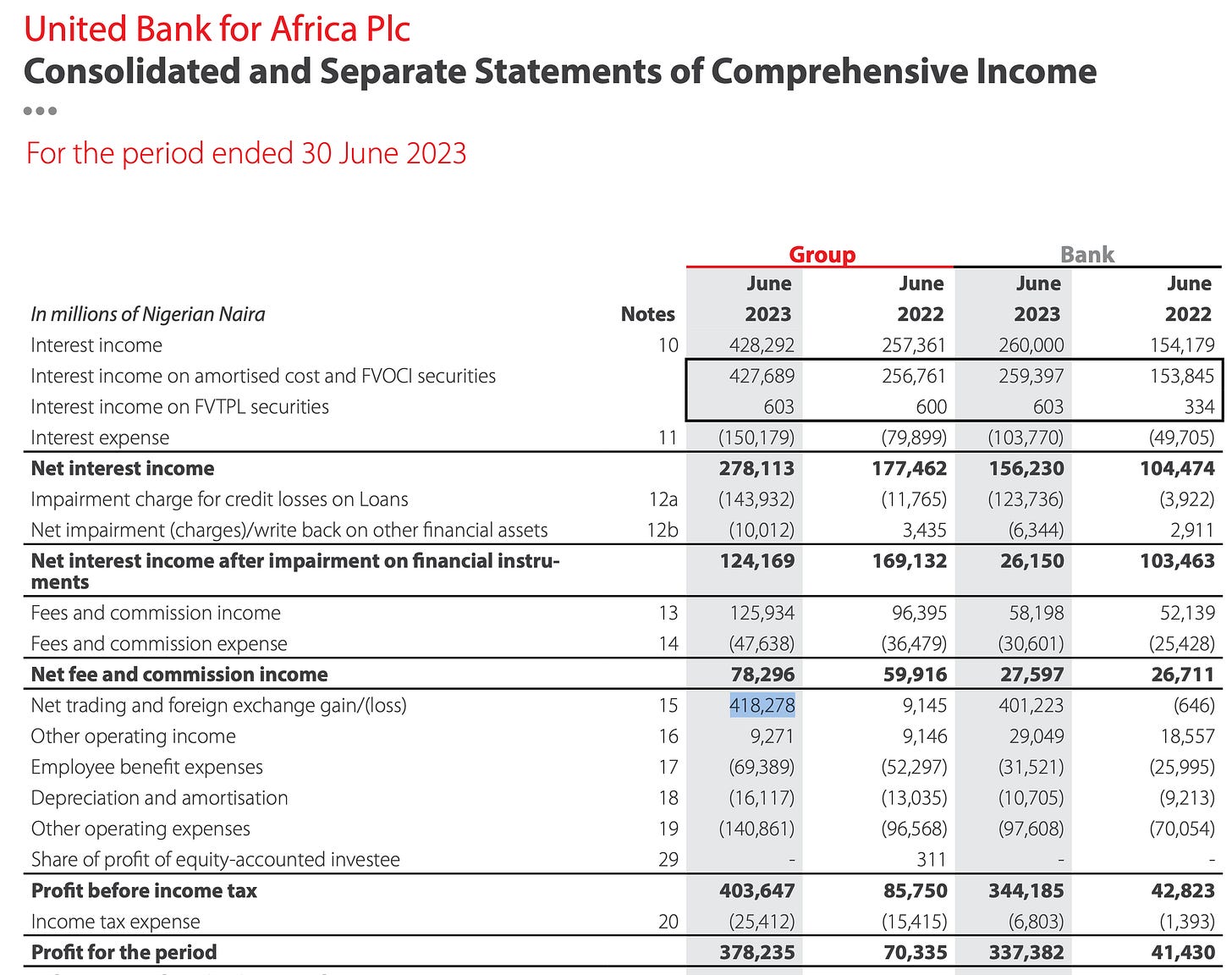

Finally, let’s check on UBA:

Unpacking that N418 billion in Note 15 gives us:

The bulk of it is N348 billion but we have to jump one more step to Note 34( c ):

UBA reports theirs slightly differently but it’s the same foreign exchange gain as we see from the comprehensive income statement. We have another $460 million booked bringing us up to roughly $2 billion dollars in gains between these 4 banks alone over the first 6 months of 2023.

What is this foreign exchange gain printing money for the banks? To oversimplify, it is the swaps the banks entered into with their regulator, that is the Central Bank of Nigeria. As we’ve discussed before, the CBN’s desperation for dollars meant it entered into some pretty expensive experiments in the name of obtaining dollars to meet the demands of the economy.

In this swap arrangement, banks handed over dollars to the CBN in exchange for some interest bearing securities. At an agreed date, the CBN promises to return the dollars to the banks. From the banks point of view - they give you a dollar, you give them back a dollar. Where the CBN finds the dollar when it is time to return it to them is not their concern. (In reality it is not always this straightforward - some of the swaps are settled in Naira at the prevailing exchange rate).

This is how we understand all those gains we saw above. Suppose that a bank swapped $1 billion with the CBN at the end of last year to be returned at the end of this current year. I can’t be bothered to check but let’s assume the exchange rate at the time was N400 to N1. On your books - since you are a Nigerian bank reporting in Naira - that would be recorded as N400 billion. 6 months later, the exchange rate has moved to N756 to $1 meaning that $1 billion is now worth N756 billion. It’s the same dollars but now worth more in Naira so you have a gain of N356 billion which you have not yet received but has effectively happened i.e. an unrealised gain. To recap the example we used in a previous post:

FVTPL stands for Fair Value Through the Profit and Loss. To explain in simple language: under IFRS (the rules that govern how you prepare your accounts), certain financial assets have to be measured at ‘fair value’. This means that if you own an asset like a stock or a bond and there is a market where that asset is traded publicly and in an orderly manner i.e. a stock exchange or bond market, you have to record the value of that asset in your books based on what you would get if you were to sell it in that public and orderly market.

So say I own one Apple share and on 31 December 2022 (the date at which I prepared my accounts), it was trading for $1,000 on the stock exchange, I will record $1,000 in my accounts as the fair value of the asset as at the date of my accounts. But you are probably thinking that the value of assets traded in public and orderly markets are always moving up and down. Yes, and that is where FVTPL comes in: it is how we measure changes in the fair value of assets from one period to the next in the accounts. If at the end of 2023, the Apple share is valued at $1,200, I will record $200 in the Profit and Loss as a gain. If it was to drop in value to $750, I will record $250 as a loss. The asset itself sits on my balance sheet (I have not sold it) but the movements in its fair value are recorded in the P&L i.e. FVTPL. This concept is useful as it's something we will come across multiple times. You will notice that a lot of things in IFRS accounting work in this way — recall that N346 billion was recorded as unrealised losses on forex in the same accounts following a similar principle.

In other words, the banks have taken a bet on the value of the Naira - relative to the dollar - and have reaped handsome rewards for it. Nothing illegal has happened here. The gains are all legit and the bet against the Naira was facilitated by the CBN itself, the self appointed defender of the Naira.

What are we really to make of a scenario where the nation’s banks are all taking highly profitable one way bets against the currency of their own country? I’m not saying banks ought to be patriotic in their search for profit - business is business. But in this scenario this is comfortably the largest source of income in their accounts and in all cases is larger than their after tax profits.

Nigeria is a very strange place.

I'm really not sure the CBN did anything wrong here. If, instead of giving that money to CBN, the banks instead kept it in their lockers and didn't touch it for a whole year, they still would have recorded the same humongous fx gain, no? The only advantage the banks gained here seems to be whatever interest they earned on those securities (I'm just going with your explanation).

The banks will always do what is in the interest of the shareholders, it's what they are expected to do. My question is did the CBN act in the interest of its own shareholders i.e. the Nigerian people? If they didn't, are there any penalties for this level of mismanagement?