The Impossible Equation

The 1979 fiscal pact that threatens Nigeria's future

Few modern states embody the paradox of endurance amid existential fragility more strikingly than Nigeria. Forged in 1914 through British imperial fiat - a fiscally expedient exercise that amalgamated its northern and southern protectorates - its borders remain largely unchanged, defying a century of centrifugal forces. This colonial contrivance, once dismissively referred to as a "mere geographical expression," by one of the country’s most prominent statesmen, has weathered commodity collapses, military dictatorships, aborted democratic transitions, and a civil war that claimed millions of lives. It has persisted despite predatory governance that has relentlessly plundered public wealth and institutions engineered to fail. Nigeria’s survival is less a triumph of statecraft than a testament to the tenacity of artificial entities.

This endurance recalls Adam Smith’s 1782 rejoinder to a despairing protégé - John Sinclair - fearing Britain’s ruin amid the American Revolutionary War: "Be assured, my young friend, that there is a great deal of ruin in a nation." Smith’s axiom - that states possess a reservoir of resilience that would require sustained, compounding folly to exhaust - finds its ultimate expression in Nigeria.

But resilience is not infinite. Nigeria now faces a threat both banal and insidious: death by technical committee. In this, the country confronts the ultimate perversion of Smith’s observation: a nation may withstand great follies, yet succumb to the accumulated weight of seemingly trivial ones.

In the beginning there was a commission

Nigeria’s fiscal system has always wrestled with a core question: how to fairly split money between the federal centre and states. This core tension of Nigerian federalism predates independence, with colonial-era commissions - Philipson (1946), Hicks-Phillipson (1951), Chick (1953), Raisman (1958), Binns (1964) - trying to devise equitable allocation formulas between the centre and regions. A pivotal innovation emerged in 1958: the Distributable Pool Account (DPA). Designed as a fiscal buffer, the DPA captured designated federally collected revenues (including shares of mining royalties and import duties) for redistribution to the regions. This acknowledged a simple truth: if the centre collected wealth, it had to share some with the regions.

But everything changed in the 1970s. State creation exercises (12 in 1967, then 19 by 1976), steadily shattered the old regional powers. At the same time, oil money flooded in, replacing taxes from farms and trade. As Nigeria prepared to return to democracy in 1979, this double shift – more states, more oil – broke the old DPA system. A burning question emerged: How could this oil wealth be split fairly between federal, state, and new local governments, and among the states themselves, without tearing the country apart?

The crunch came in 1977. Oil-rich regions demanded a bigger cut based on "derivation" (where the oil was pumped), while others pushed for equal shares nationwide. With the Dina Committee's (1968) proposals deemed too radical by the military, General Obasanjo's outgoing regime sought constitutional legitimacy for a new revenue formula. The result was the Aboyade Technical Committee on Revenue Allocation: a six-member panel of respected economists and technocrats, including Chairman Ojetunji Aboyade, Owodunni Teriba, Green Nwankwo, and northern insider Mamman Daura (a Dina Committee veteran and nephew of Nigeria’s former President Buhari, though three years older). Tasked with forging an "equitable" distribution framework across federal, state, and local tiers, its recommendations were designed for direct incorporation into the 1979 Constitution by the Constituent Assembly.

1978’s Fiscal Revolution

Born in 1931 and rarely seen without his signature bowtie, Professor Ojetunji Aboyade secured a Cambridge PhD before age thirty, establishing himself as a towering intellectual force. At the University of Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo University), he belonged to the legendary “Aparo Mafia” - a group of professors whose pursuits took them into the surrounding jungle as amateur bird hunters. Once, according to the Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka, he nearly came to blows with General Obasanjo after an argument in which he branded Obasanjo an “economic illiterate.” Aboyade’s world centred on the life of the mind, a realm shared with his wife Beatrice, the first sub-Saharan African woman to earn a doctorate in English literature. He died in 1994, long before his ideas - for better or worse - would fundamentally reshape Nigeria.

Aboyade’s committee delivered its report in early 1978, proposing quite the fiscal revolution at the time. Its cornerstone innovation was the Federation Account: a unitary pool mandating all federally collected revenues - oil, taxes, duties - be consolidated before distribution. This shattered the precedent of selective revenue-sharing via the Distributable Pool Account, embodying a radical vision of centralised collection as a catalyst for national cohesion.

The ambition extended further. It established Nigeria’s first tripartite vertical formula, allocating Federation Account proceeds 60 percent to the federal government, 30 percent collectively to states, and - revolutionarily - 10 percent directly to local governments, constitutionally enshrining them as a third fiscal tier. Crucially, states and localities now gained automatic shares of all revenues, including lucrative oil streams previously monopolised by the center. A three percent Special Grants Account, carved from the federal share, acknowledged mineral-producing regions’ unique needs while deftly subsuming the contentious derivation principle within federal discretion.

Most technically audacious was the horizontal allocation mechanism. Replacing crude metrics like population or derivation, Aboyade introduced a weighted five-factor formula privileging equity ("equality of access to development opportunities": 25 percent), national integration ("minimum standards": 22 percent), and performance ("absorptive capacity": 20 percent; "revenue effort": 18 percent; "fiscal efficiency": 15 percent). This reoriented distribution from revenue origin to developmental purpose, with incremental application ensuring no state suffered abrupt losses. This shifted focus from where money came from to how it could build the nation – while guaranteeing no state lost money overnight. The blueprint was brilliant but risky: central control might prevent breakup... or accelerate it.

The birth of the Federation Account

The Aboyade Committee’s 1978 report immediately collided with political realities. Though forwarded to the Constituent Assembly for inclusion in the constitution, its proposals were rejected as impractically complex - critics lambasted opaque metrics like "absorptive capacity" and "fiscal efficiency." Oil-producing states rebelled against the virtual erasure of derivation; others decried the formula’s centralising tilt (retaining 57–60 percent for the federal tier). A pivotal blow came from superstar economist Pius Okigbo, whose forensic critique during assembly debates galvanised opposition. Consequently, the military regime suppressed the report, never publishing it as policy.

Yet Aboyade’s core architectural innovation endured: the Federation Account. Codified in Sections 149(1)–(2) of Nigeria’s 1979 Constitution, this mandate required all federal revenues - petroleum profits, customs duties, corporate taxes - to flow into a single pool before distribution. Crucially, it abolished revenue earmarking, recognising federal, state, and local governments as co-equal beneficiaries. While the constitution deferred exact percentages to legislation (departing from Aboyade’s 60/30/10 specificity), it institutionalised his core principles: centralised collection, three-tier sharing, and the dissolution of distinctions between revenue streams. This delivered the final blow to the 1960s derivation regime, which had guaranteed regions 50 percent of mining royalties. By replacing the Distributable Pool Account with a universal revenue conduit, the 1979 framework profoundly centralised fiscal federalism - a design preserved verbatim in Section 162 of Nigeria’s current 1999 Constitution. The Federation Account thus stands as Aboyade’s indelible structural legacy: a revolutionary idea that outlived its architect to redefine Nigerian statecraft.

The unusual Nigerian state

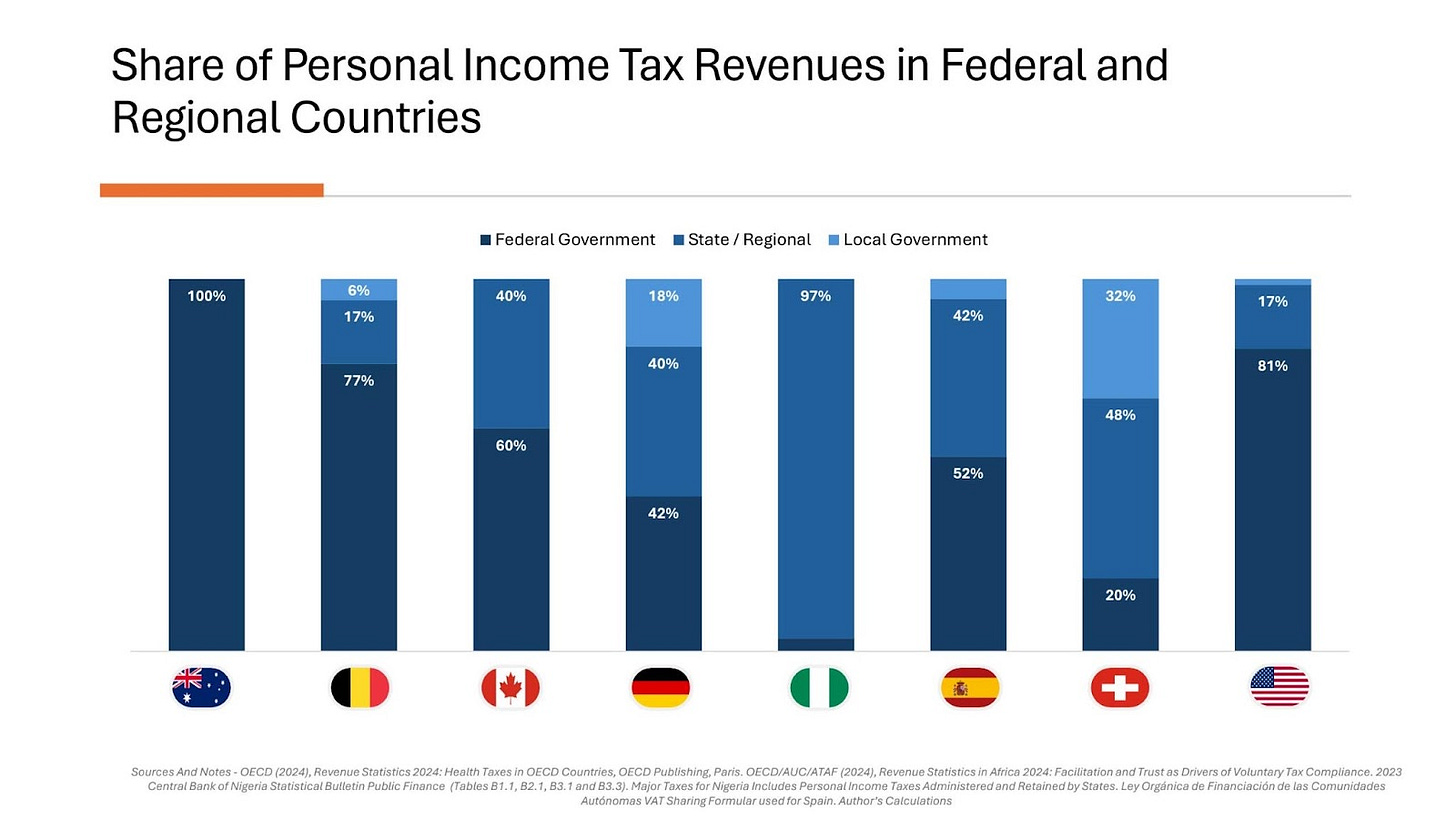

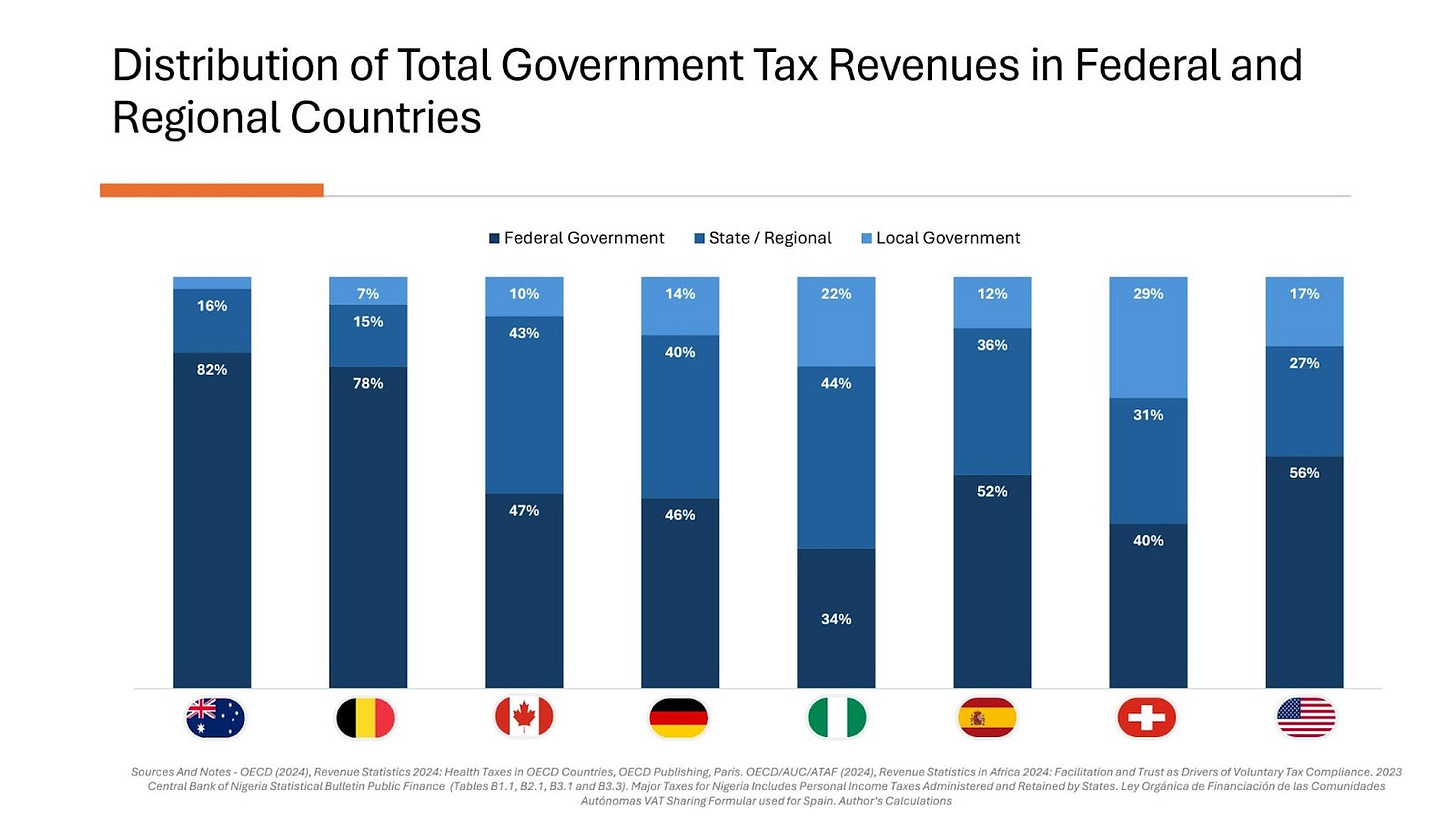

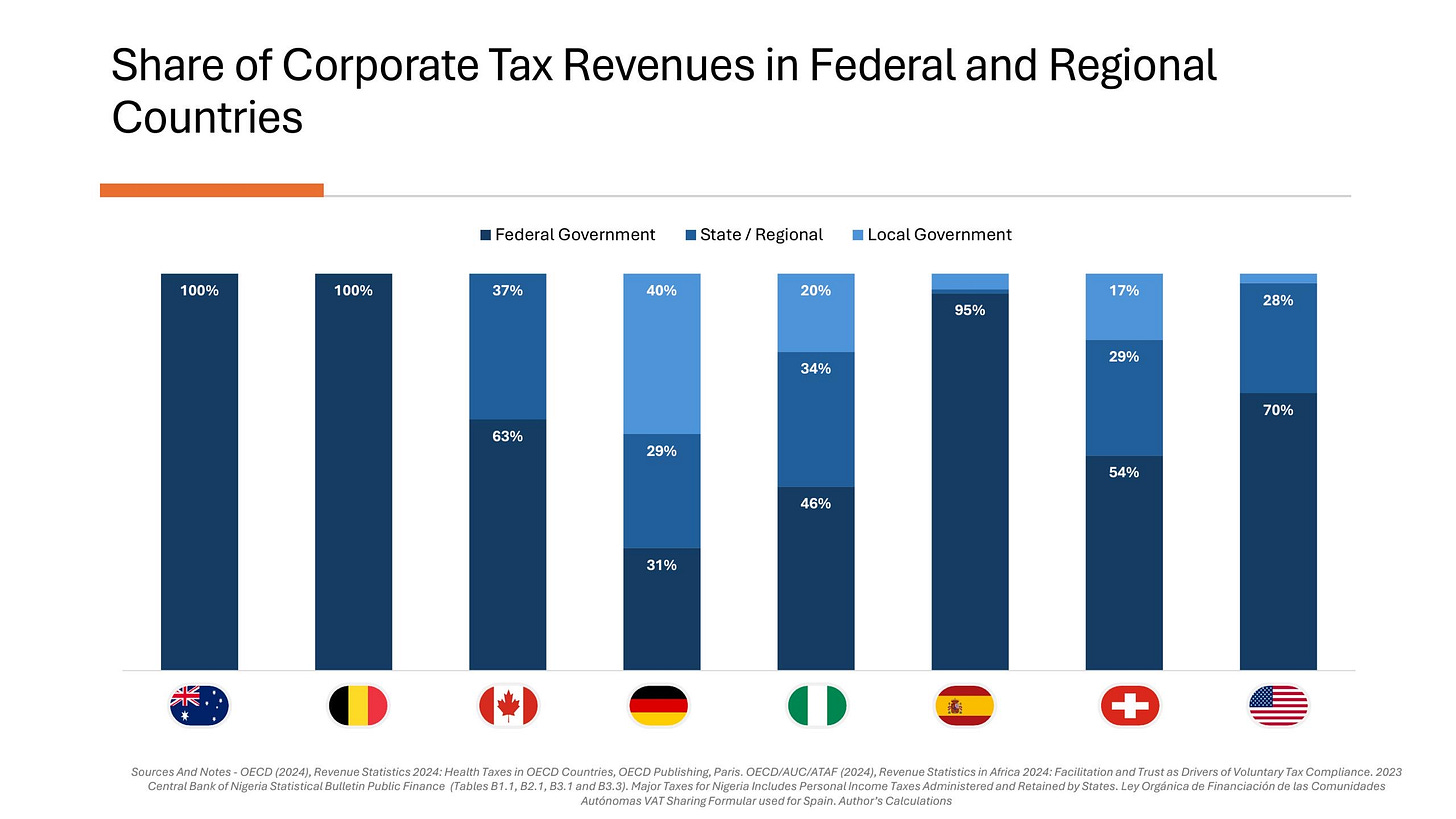

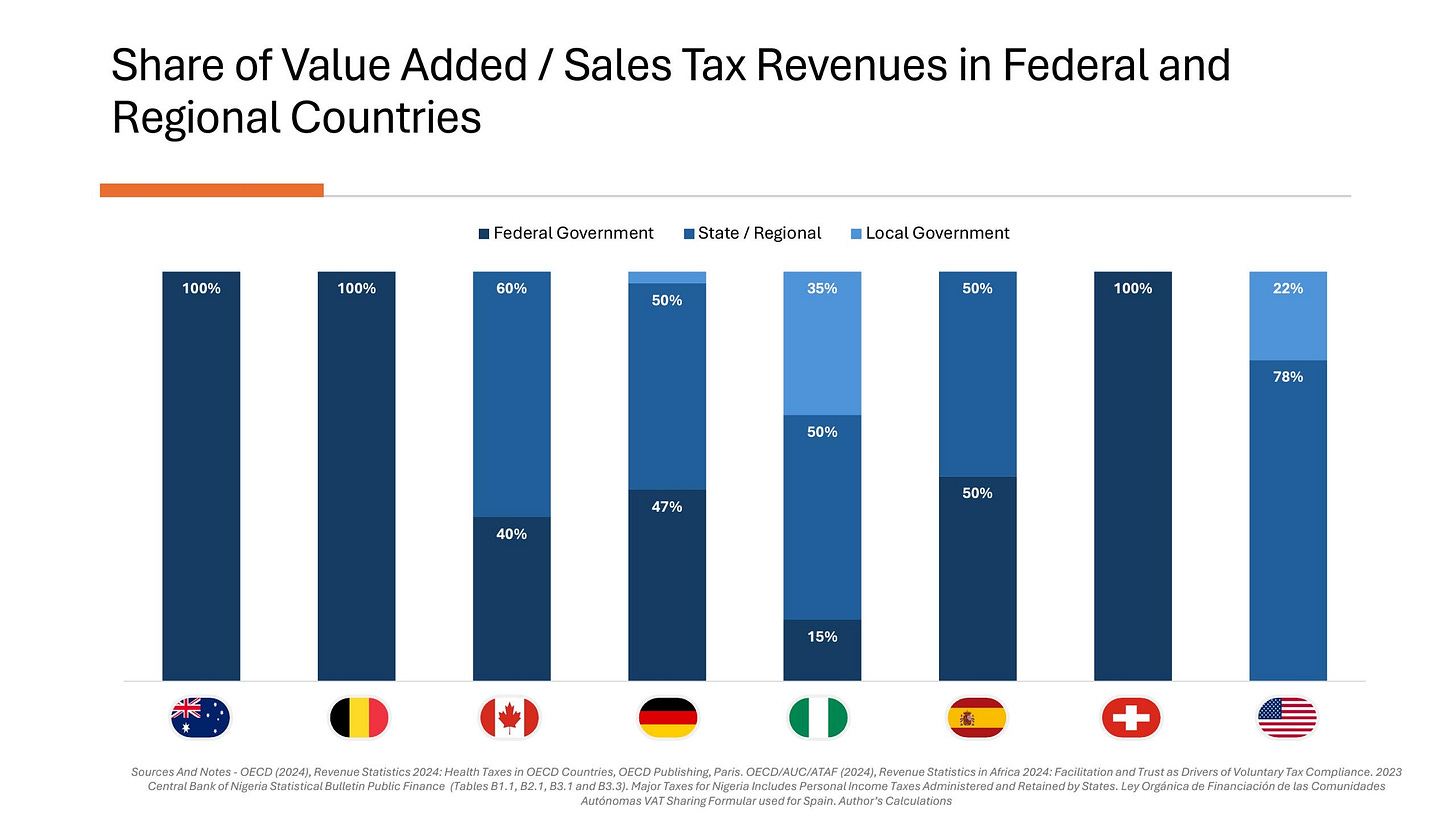

Ideas calcify into institutions often with unintended consequences. Nigeria now occupies an almost unique position among global federations: its central government retains not a single major tax exclusively. Contrast this with the U.S., where federal payroll taxes fund Medicare/Medicaid without state sharing, or Spain, where corporate taxes remain wholly central while 50 percent of VAT and payroll taxes devolve to the regions. Even in decentralised Canada, a high-earning Ontarian pays distinct federal and provincial income streams (e.g., ~CAD$140,000 federal payroll taxes + CAD$58,000 provincial taxes on a CAD$500,000 income). Nigeria’s constitutional architecture forbids such bifurcation. By mandating all revenues enter the Federation Account the system eviscerates federal fiscal autonomy. The centre becomes a distributor, not an owner, of its revenue base (uniquely in the world, Nigeria’s federal government does not levy income taxes on its citizens except for a very limited selection of the armed forces and foreign affairs officials.)

The Federation Account’s creation crystallised Nigeria’s fatal flaw: it transformed governance into a zero-sum scramble for petrodollars, not value creation. By centralising all revenues into a single pool - especially volatile oil rents - it created a clear and visible target for rapacious rent-seeking while eroding fiscal discipline. When prices spiked, this "sharing psychosis" became a fiscal drug: states and federal actors feasted on windfalls rather than investing in productivity. As Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Nigeria’s former finance minister and current Director General of the World Trade Organisation, would later document, this architecture entrenched the "bad habit" of “sharing” as statecraft in “Nigeria's extreme version of fiscal decentralisation” - a pathology that would systematically sabotage attempts at responsible resource management.

In her 2018 book, Fighting Corruption is Dangerous, Okonjo-Iweala detailed how Nigeria’s revenue-sharing obsession gutted her efforts to stabilise oil revenues. As Finance Minister (2003-2006), she established an Excess Crude Account (ECA) underpinned by an oil-price fiscal rule: budget conservatively at $35/barrel, save surpluses during booms, and deploy reserves during busts. By 2007, $22 billion had been saved, proving its efficacy when ECA funds shielded Nigeria from the 2008-09 global crisis (avoiding World Bank loans).

Yet state governors - invoking Section 162 of the 1999 Constitution - waged war against the ECA, demanding immediate distribution of all revenues. Despite counterarguments that Section 16 of the same constitution granted the state duty to "harness resources for national prosperity," governors decried savings as illegal. Though Obasanjo temporarily resisted, his successor, President Yar’Adua, capitulated during the 2009 oil crash when prices cratered to $38/barrel from their previous high of $147, releasing ECA funds as stimulus. Crucially, governors refused to stop withdrawals post-crisis, addicting states to unearned windfalls. By 2011, the ECA plummeted from $22bn to $4bn.

Okonjo-Iweala’s subsequent push for a Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) - legally insulated with Stabilisation, Future Generations, and Infrastructure windows - faced identical sabotage. Governors again weaponised Section 162, blocking SWF capitalisation. Her experience epitomises Nigeria’s self-sabotaging fiscal loop: the Federation Account’s design rewards short-term sharing while punishing intergenerational stewardship.

When the state is not a state

Nigeria now faces an existential paradox: the federal government’s revenue base steadily erodes while its constitutional burdens remain unchanged (or increase and increase). The Federation Account - conceived as a unifying mechanism - has become a perpetual target in fiscal negotiations, with the centre sacrificing revenue shares to secure ephemeral political consensus. Each "reform" compounds this attrition, as seen most recently in the Nigerian tax Act, signed by President Tinubu in June 2025, which came with a 5-point reduction in the federal VAT share from 15 percent to 10 percent, transferring fiscal oxygen to states while further asphyxiating federal capacity. This ritualised dismemberment has become a zero-sum game where the centre’s surrender is as sure as night follows day.

The list of taxes that the federal government once exclusively retained but has steadily lost is neither short nor trivial. Consider the trajectory: Company profits tax - wholly federal in every pre-1979 framework - now feeds the Federation Account’s sharing matrix. Import duties on alcoholic beverages, retained 100 percent by the centre as late as 1975, became communal property. All other excise duties met identical fate. Most consequentially, petroleum profits tax - 100 percent federal in every pre-1979 framework - became subject to the Federation Account’s tripartite dissection. Each concession, framed as “federal generosity,” in fact eroded the centre’s fiscal sovereignty while doing nothing to recalibrate its constitutional burdens.

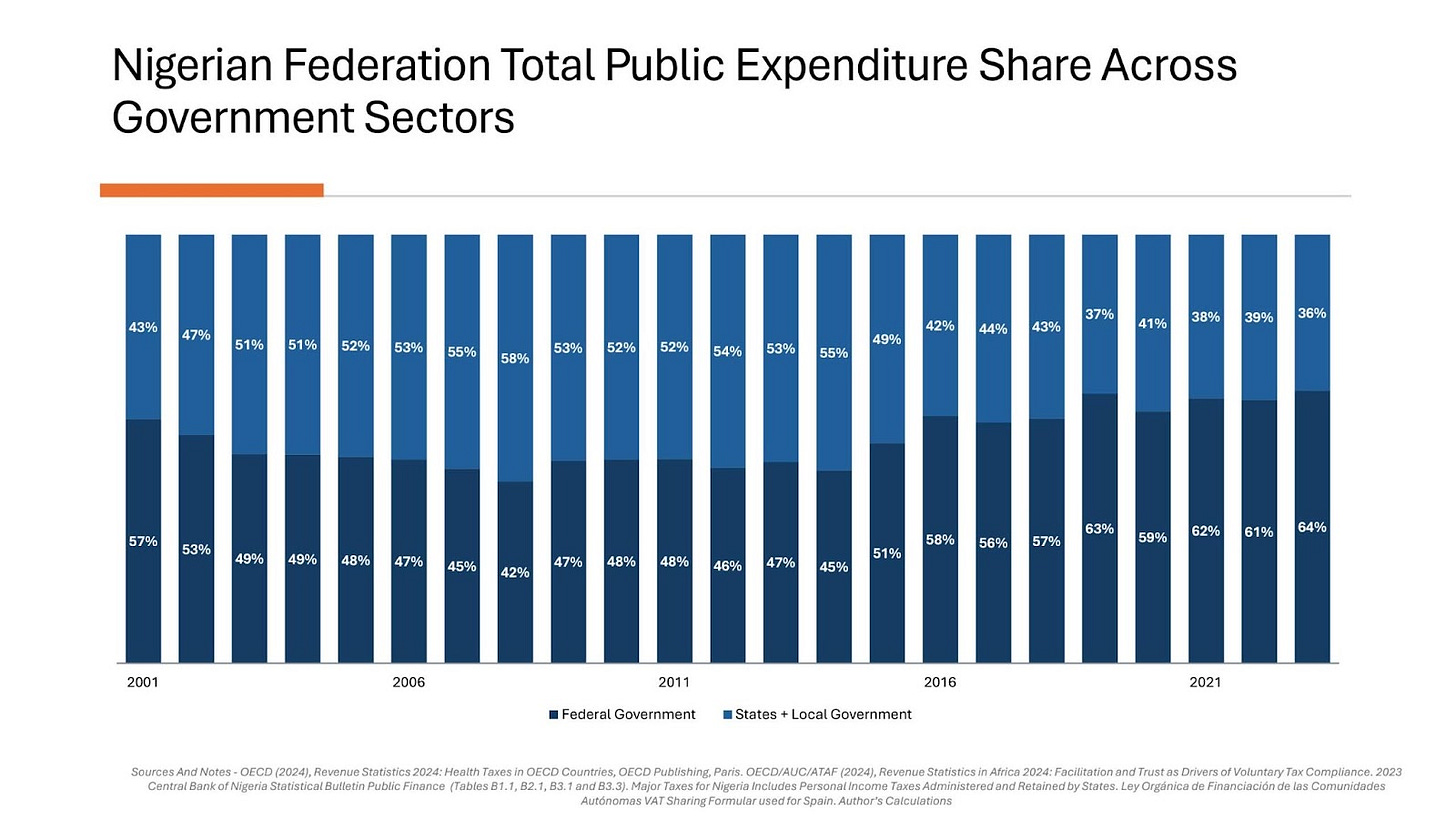

The brutal arithmetic reveals the impossible equation: federal revenue shares have plunged from 49 percent in 2002 to 37 percent in 2023, cratering to a low of 32 percent in May 2025’s Federation Account Allocation Committee (FAAC) disbursement - the monthly ritual where the states and federal government gather to share revenues. Yet constitutional burdens remain immovable: defence now consumes more than $4 billion annually driven by the 14-year war against the insurgent Boko Haram in the north east; debt servicing will claim $10.2 billion in 2025, and interstate highways/railways drain the hollowed centre. Subnational units now command over 60 percent of FAAC revenues while executing less than 40 percent of public expenditure (and even transferring their fiscal misadventures to the centre) - a lethal asymmetry.

A warning from the future

Nigeria now reaps the harvest of this fiscal unraveling: a federal government stripped of capacity by design. Critical national projects - from human capital development to power infrastructure - cannot thrive when resources are fragmented across 36 states and 774 local governments. This fiscal diaspora ensures education quality fractures into 36 disconnected experiments, condemning a child’s future to their geographic lottery. Meanwhile, ports, roads, and defence cry out for funding. The result is a centre paralysed by contradiction: constitutionally burdened with macro-scale duties yet forced to pursue them with micro-scaled, diluted resources. Diffused, the state fails everywhere; consolidated, it might have succeeded somewhere.

If this fiscal death by a thousand cuts continues, Nigeria risks a slow-motion erosion of stability in West Africa's anchor nation. Africa's largest economy and most populous democracy becoming progressively ungovernable could trigger serious humanitarian consequences, regional insecurity, and ripple effects across global markets – destabilising the Gulf of Guinea and beyond.

Yet advocating for recentralisation remains politically toxic. In today’s Nigeria, where powerful governors weaponise “fiscal federalism” to demand more of shared resources, any call to strengthen the federal purse is dismissed as authoritarian nostalgia. Even the political elite - who feverishly jostle for a weakened presidency - fail to grasp the paradox: they fight to control a centre being systematically bled of the capacity to govern. This collective denial does not negate the existential math. As the Raisman Commission warned six decades ago, “the financial stability of the federal centre must be the main guarantee of the financial stability of Nigeria as a whole.” Without it, the nation risks becoming what it long resisted: a mere geographical expression, etched in the ruins of its own design.

So, what now? This has been a diagnosis, not a prescription. The next post(s) will dig further into the data to show how Nigeria is, quite literally, sharing itself to death — and consider both the expected and uncomfortable solutions. Thanks for staying with it.

Edit: Earlier version referred to Ayo Teriba as a member of the Aboyade Technical Committee. In fact it was Professor Owodunni Teriba

Very interesting article and lays out the fiscal reality of an increasingly weakened central political authority.

As you will know, I have long argued that the nature or culture of the region politically tilts towards decentralisation and away from the accumulation of political authority by anyone. No thanks to yams. Historical blips aside. I wonder if this is another manifestation of that history. Of course decentralisation is not in of itself a bad thing. But it leaves many questions unanswered such as how to efficiently provide public goods that by the nature need to be in some way centralised, such as security or monetary policy like you mention. I wonder if some answers lie in how the Swiss govt operates, or even the EU as an institution.

Second thought. The 1970s brought about a dramatic change in the structure of government revenues thanks to both oil discovery and the oil boom. I mean, if oil exports made up close to 40% of GDP then the question rightly is how to fairly distribute that. And the answer was born. Now that oil is circa 8% the question has changed but the answer is still the same old answer. I had hoped that a CBN debt fuelled inflation spiral would be the spark for a national agenda around revising the fiscal landscape. In a way it was but the reforms seemed to have been mismanaged on the political front and so we are left with largely administrative reforms but no fundamental structural solution.

Either way. Good article.

Brilliant and well-researched piece as expected. Fundamentally, my opinion about Nigeria remains unequivocally clear as ever: it is not a cohesive nation. With various groups competing for access to resources, it is not surprising that we've found ourselves in a seemingly fiscal loop. But we need to be cautious. As much as a powerful central government is appealing, it possesses vulnerabilities that may prove existential to the existence of the country. Take for example the cutthroat competition for power between ethnic/regional groups and the consequences it could have on state's existence.

A powerful federal government under the helm of an incompetent, corrupt individual is equally a reality that cannot be ignored. Nigeria as a concept and a reality are different. The creation of local government, for example is an aberration that can only be found in a place like Nigeria but it becomes interesting when you realize that not all states in Nigeria are culturally homogenous and some of these local government are outlets for political expression of minority ethnic groups. The inability of the Nigerian political class to admit that the country is a charade politically will always result in a convoluted fiscal mess like this.