The Elephant

An embarrassing confession about art and what it means to be in the presence of greatness

In January of 2017, an email from Dele Olojede arrived, inviting me to collaborate on a project marking an organisation’s upcoming tenth anniversary. The centerpiece was to be a commemorative coffee table book documenting its history. “You have a very good understanding of the subject matter and you write very well,” he noted. He added, “I anticipate that Victor Ehikhamenor will handle the design and photography, as well as work with the printing house in Johannesburg to guarantee very high production values.” While flattering, his generous assessment belied my own reality. At the time, my writing had garnered a measure of online notoriety, but what I had was little more than raw talent - a gift I would soon learn required considerable refinement in both craft and purpose.

His proposed workflow was: I would conduct the interviews and draft the narratives, while he would serve as editor-in-chief, refining every line. Only upon our final approval would Victor Ehikhamenor assume command, translating our text into his visual design. This is Dele’s gift, which lies not just in spotting talent, but in orchestrating its connection.

The moment I submitted my first drafts for his edit, the earlier flattery crystallised into clarity. My immediate conclusion was a humbled respect for the fact that Pulitzer Prizes are earned, not handed out. Under his guidance, I encountered a universe I had never before considered: punctuation nestled inside brackets (like this.) rather than outside, and the rule of spelling out numbers up to ten (three, seven) before using numerals thereafter. These were elementary principles, yet they had been gaps in my writing, unnoticed until a master editor took the time to point them out.

Then there was my tendency toward repetition and verbosity. I would watch him excise entire sentences, even paragraphs, from my drafts. My instinct was to protest, but he would calmly challenge me to read the condensed version and confirm if the essential point had been lost. Invariably, it remained, proving his axiom that five words can almost always be distilled into two. I was learning to tighten my prose and, more importantly, to respect the reader’s intelligence - to trust that a point could land without a lengthy explanation.

But I digress (so much for turning my back on verbosity eh?) The project, for all our initial enthusiasm, did not proceed to plan. It was beset by innumerable delays and mounting cost overruns. A symptom of its unravelling was Victor’s gradual withdrawal; his attention, from my vantage point, became increasingly diverted by what I could only conclude was ‘other stuff’.

This sense of fragmented understanding brings to mind the Buddhist Tittha Sutta and its parable of the six blind men and an elephant. Having never encountered such a creature, each man sought to comprehend it by touch. The first, feeling its flank, declared it a wall. The second, grasping a tusk, insisted it was a spear. The third, holding the trunk, argued it was a snake, while the fourth, embracing a leg, knew it to be a tree trunk. The fifth, touching an ear, proclaimed it a fan, and the sixth, grabbing the tail, was certain he held a rope. The parable concludes with a heated argument, each man certain of his own truth and convinced the others are fools. Its core lesson is that human understanding is often shackled by individual perspective.

The truth is, I cannot say why I failed to perceive the artistry before me. I fancy myself a reasonably curious individual, yet the most obvious realities are often the last we truly see. What does it mean to have been in the presence of greatness and remained unaware? I could blame the pressures of our time-pressured project - though this feels like a feeble excuse. What embarrasses me to this day is the simple, unvarnished fact: I did not truly know Victor was an artist. I may have known it in the abstract, of course, but I did not know it. The distinction, I have learned, is everything.

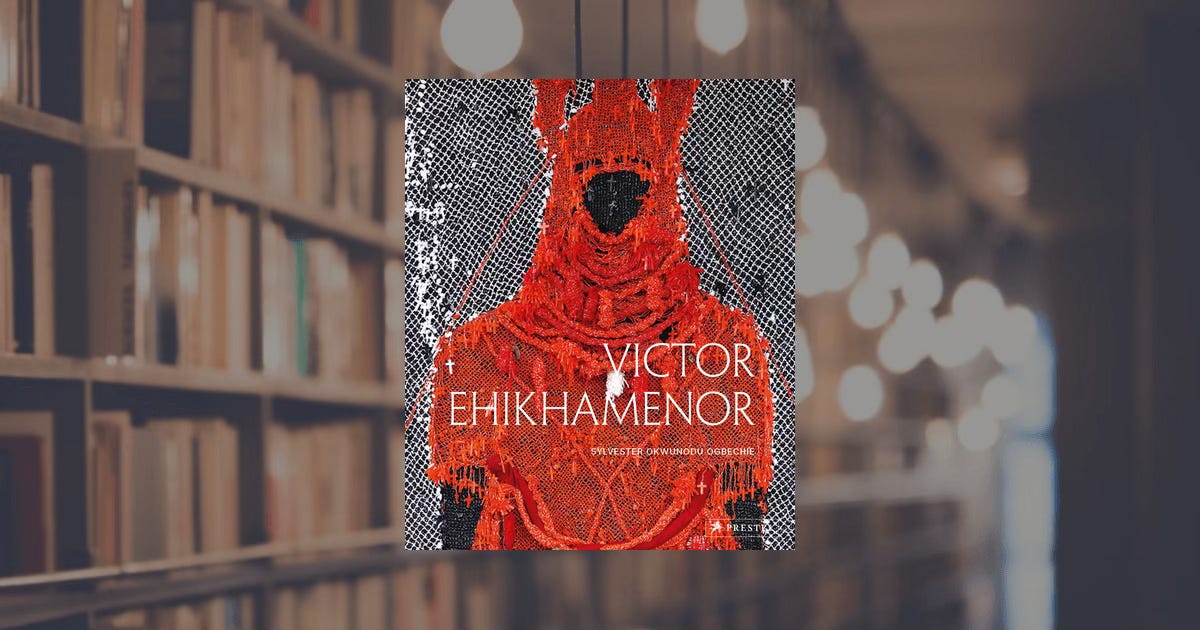

These reflections surfaced anew when a friend recently gifted me a copy of Chronicles of the Enchanted World, a volume documenting Victor Ehikhamenor’s ascent to become one of Africa’s most celebrated artists over the last two decades. With the clarity of hindsight, I understood that I had been in the presence of greatness in the making, yet had failed to perceive its full scope. My own view of him had been confined to that of an excellent graphic designer. This limited perception was precisely illuminated early in the book, edited by the Nigerian-American art historian Sylvester Ogbechie, which notes: “In addition to his career as an artist, Ehikhamenor is also a prolific photographer, graphic designer [the part of the elephant I had grasped], and writer whose work criticises Nigeria’s political corruption and Africa’s marginal role in global economics.”

Later that same year, the true scale of my oversight began to unravel. An email arrived inviting me to a private viewing of Victor’s exhibition, In the Kingdom of this World, at London’s Tyburn Gallery. The accompanying note described “a series of intricate perforated works on paper and a new body of work composed of rosaries sewn on canvases and lace material,” in which the artist “weaves elaborate images depicting mythical and royal figures.” It explained that these works “reference the imagery and symbolism of both Edo traditional religion and Catholicism, the dual aesthetic and spiritual traditions which infused the artist’s upbringing.” Yet it was only upon arriving at the gallery that the scales truly fell from my eyes. The “private viewing” was a packed, standing-room-only affair, and in that moment, it became clear that the man I had known only as a graphic designer was, to put it mildly, a great deal more. I was witnessing an artistic force whose work was unmistakably destined for the world stage.

To the extent that such a thing as an eye for art exists, I am confident I do not possess it. My own artistic inclinations are a mystery, even to me; I don’t so much know what I like as I stumble upon it, and I am woefully unequipped to articulate why. I can profess a general fondness for bright colours, but which ones? Blue, I suppose? Certainly. Red? Definitely. As I type this in my study, a canvas of Sisi Eko is gazing down at me from the wall. I think I like it, but frankly, who knows.

Yet, I can state with certainty that from the first moment I saw one of Victor Ehikhamenor’s perforated works, I was captivated (they have no colours, by the way.) This appears to be a common experience; in a conversation with Toni Kan, when asked which of his art forms has found the most acceptance, Ehikhamenor himself confirmed, “I’ll say the ‘Perforation’ series.” This widespread appeal is understandable, for the works possess an intrinsic, almost magnetic quality that provokes a delightfully presumptuous impulse: the urge to touch them. It is an impulse that, as Sylvester Ogbechie observes, “would conceivably break down the barrier between artwork and audience.” And as the artist tells it, this singular technique was born out of a happy accident:

It started in 2013 when I brought some handmade papers from London and didn’t want to just paint on them. I started punching one of the papers with a screwdriver to create texture. When I flipped the paper over, I was pleasantly surprised by the effect. Right there and then I decided to use nails to create my iconography. Since then, the idea and style has expanded to much larger paper than when I first started.

From that initial spark of inspiration found in a blank piece of paper, his artistic vision expanded to draw upon the worlds of literary giants as diverse as Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe, and the Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier. This deep literary affinity is unsurprising, given his own accomplished background as a writer - another facet of the elephant. He reveals that the same creative currents fuel both his writing and his art, explaining that he employs a parallel process for bringing a novel and a painting to life: “I ask the same kind of questions of both regarding plot, design, forms and symbolism.”

To attempt a review of a book about an artist like Victor Ehikhamenor feels a task beyond my capacity - a certain path toward further embarrassment. How does one adequately capture a practice that encompasses rosary beads and charcoal, shredded paper and oil drums, bronze heads and deep invocations of Benin history? It is the voice of an artist who knows his own mind and speaks it without apology (a fact Damien Hirst could corroborate). This is, of course, another formidable part of the elephant. I find my own inadequacy for the task echoed by Sylvester Ogbechie, who toward the end of his essay poses the essential question: “What does it mean to discuss the career of a contemporary artist whose practice is still unfolding?”

Many years ago, I stumbled upon a 19th-century aphorism by the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer that never fails to amuse me: “Treat a work of art like a prince: let it speak to you first.” I have the habit of visiting a gallery in every city I find myself. Now, I often stand before a piece that utterly baffles me, and, recalling Schopenhauer’s dictum, I wait. I afford it that royal privilege of speaking first. But as the seconds tick by, a practical thought inevitably arises: Well? I have things to do. After silence has claimed its inevitable victory, I move on to the next piece, forever hoping to catch a whisper from something determined to remain mute.

And so I continue my habit, hoping not to be blind to greatness again, seeking out the things that delight my eye and learning to appreciate them as fully as I can. Perhaps one day the prince will deign to speak; perhaps he will not. There is some irony in the fact that our own collaborative project - the coffee table book - never reached the conclusion we hoped for, while I now hold in my hands this beautiful volume that so fully documents the incredible talent I failed to properly see. This book, at least, found its way to completion, and for that, I am profoundly glad. It is a finished portrait of the very elephant I could only feel parts of, a lasting testament that some visions are simply too great to remain silent forever.

A beautiful read!

I love this. I knew him and Tokini Peterside from the days of 234Next and have always admired his work. I should start curating his works on my Instagram page.