Trade is one of the oldest economic institutions in the world. For millennia, long before the establishment of states and national borders, people around the globe engaged in mutually beneficial commercial exchanges. Trade has largely been profitable for all parties where there is no conquest, fostering economic growth and cooperation among different groups. Paradoxically, trade policies have always been fraught with controversy. Disagreements over tariffs, market access, and how they affect the interests of influential groups have frequently led to tensions between nations.

The debate over trade policy continues today unabated, to the point where protectionism fused with nationalist politics is now the accepted wisdom in many halls that used to be sanctuaries of free trade.

The role of trade in rapid economic growth

In the context of the countries that saw rapid growth in the last five decades, trade, especially the development of globally competitive export sectors, was very instrumental. Despite these successful examples, many low-income countries persist with protectionist import-substitution trade policies, which are detrimental to their growth.

A recent paper argued that import substitution policies—which became popular in the 1950s and focused on building self-sufficient domestic industries protected from foreign competition through high tariffs and sometimes outright import bans—almost always resulted in "inefficiencies, lack of innovation, and economic stagnation." Export-oriented policies, on the other hand, result in good economic outcomes through competition, innovation, and integration of firms into the global economy. The authors argue state intervention is not inherently bad, but it is often counterproductive when used for import substitution. Instead, policy should focus on integrating domestic firms with the world through exports.

Missed opportunities in low-income countries

Why does trade continue to be a missed opportunity for many low-income countries, especially in Africa? International trade agreements can allow countries to build competitive export sectors, create jobs, and reduce poverty. A famed example is the MultiFibre Arrangement (MFA) of 1974, which was designed to curb textile exports to developed countries but ended up helping Bangladesh build a $50 billion garments export industry.

The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), passed by the U.S. Congress in 2000, was conceived to perform the Bangladeshi miracle in Africa. The law afforded preferential treatment to a range of African exports, with apparel being the most significant. According to a new paper by economists Arvind Subramanian and Justin Sandefur, Africa enjoyed a textile boom on the back of AGOA until about 2005, when the MFA expired and China started eating Africa's lunch. Since then, Africa has been unable to productively exploit AGOA for growth and transformation. AGOA is up for renewal in 2025, and Sandefur and Subramanian have some policy suggestions they think will make it work better, which I will return to. But it is important to understand why trade has not lived up to its promise.

The Ladder of Development

American political economist and former national security adviser Walt Rostow popularised the metaphor that economic development happens in stages comparable to a ladder. The ladder metaphor visualizes these stages as rungs on a ladder. Each step up the ladder represents progress in economic development, including levels of income, industrialisation, and technological advancement—implying that countries move up by producing and exporting more complex goods.

Researchers have noted that international trade dynamics and policies can sometimes determine when and how countries move up the ladder. Countries can be "helped" to move up the ladder - as was the case with Bangladesh - and they can also be held down and remain stuck in a low level of productive capability, with huge implications for their development. This is why poor countries can 'lose' from trade, and trade policies have to be carefully designed.

Trading to Win

Economist David Atkins noted that trade policies in many low-income countries are plagued by several distortions across firms, labour markets, and institutions. He advised that the design and implementation of trade policies need to factor these distortions for trade policies to be effective. Dani Rodrik, a trade economics veteran, also warned that the gains from fixing trade distortions might be limited due to factors like macroeconomic instability. But despite these cautious notes, and the variations that exist in the experiences of different countries, the evidence remains strong that reforming trade has significant positive contribution to economic development.

The likely renewal of AGOA next year offers another opportunity for African countries to halt the dismal performance on leveraging trade for economic growth and industrialisation. Sandefur and Subramanian had some useful proposals in their paper. The big one is for the U.S to provide subsidies to American firms to source from Africa. They believe this incentive will boost trade and enhance AGOA's impact. Other proposals include direct financial support through international development agencies to sustain a manufacturing ecosystem in Africa. These are good proposals but they do not address the domestic policy imperatives of African governments on how to make trade work. I will outline three complimentary proposals.

Want It

I know that sounds obvious and almost redundant, but it is important and neglected. I once asked development economist Lant Pritchett why Vietnam has been so successful with education policies, and his first answer was 'because they wanted to’. You can say the same about the success of Vietnam in exports and industrial upgrading. Trade policy cannot be separated from overall development policy - and African countries often do not have a clear plan and commitment to transforming their economies.

Making trade policies work involves many political fights against strong domestic forces of rent-seeking and state capture - and this requires political leaders and policymakers to prioritise development over these strong forces.

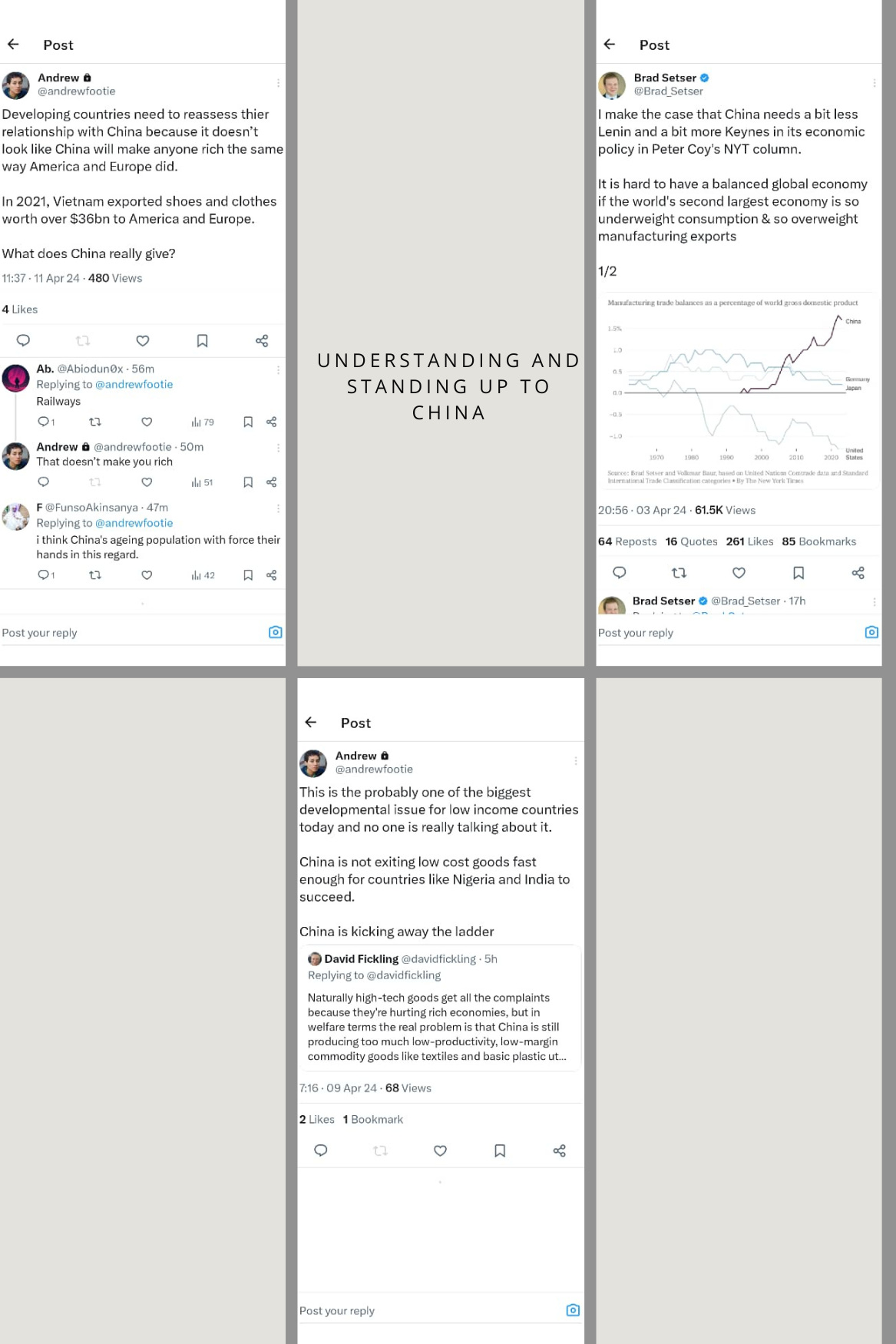

Take China Seriously

For almost a decade, trade economists have been talking about the 'China shock' - which is analysing and quantifying the effect of China's economic rise to many Western economies. I believe this became part of the intellectual backbone for the trade war between the U.S and China. Of course, this has grown into economic currents that might reshape the structure of the global economy, for better or worse. But the important point here is that Africa is not only missing from that debate, it has failed to leverage the relationship with China for meaningful economic development.

China is mainly treated as a big infrastructure finance partner, or more cynically, a source of 'loans without questions'. China's entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 was an important economic event which significantly altered global trade dynamics. Most countries benefited due to lower prices and increased trade volumes owing to China's export surge. But as some economists have noted, countries also experienced competition in their less complex sectors. This reduced opportunities for many countries to learn and upgrade through exporting, and thus move up the ladder.

For example, when the MFA expired in 2005, China's apparel export to the U.S grew quickly that it ended whatever brief textile boom Africa enjoyed under AGOA. According to Sandefur and Subramanian, China's apparel export grew to a peak of 38% of U.S imports in 2010. This has since reduced a bit, but Africa's lunch has already been eaten and the table cleared.

The central point here is not to advocate an adversarial relationship with China - rather to recognise that China plays the trade game to win and Africa needs to do the same. It should be clear to everyone now that China is not just 'another East Asian miracle'. Dani Rodrik noted years ago that China's manufacturing capability and performance transcends its income. This is because China's ambitions and influence in the world today has grown beyond the reform era goal of 'getting rich first'. It wants to compete on technology, geopolitics, science, and other frontiers that will shape the twenty-first century. Africa needs to restructure its relationship with China beyond cheap credits.

Firstly, we need to leverage China's experience with development escalators like Special Economic Zones to industrialise. No more bridges and railways to nowhere. We need thriving high-performing economic niches with positive spillovers to the rest of the economy. Secondly, our trade relationship with China needs to be more coherent and strategic. China's geopolitical ambition has put it in a position where it occupies multiple steps on the ladder. China has moved to more complex exports but refuses to exit the less complex sectors. Africa should no longer ignore this. Trade relationship with China into the future must involve transfer of technical know-how to local firms, and market access for local firms in China.

Seize the Moment

Africa's strategy on trade should not just be about China. The world is becoming increasing fractured, and geopolitics seem to be the foremost consideration in everything. Africa needs to cease to be the mere object of history. In choosing friends and allies, Africa must be clear-eyed about its priorities. The globalisation of several conflicts has left Africa quite vulnerable due to lack of basic capability problems of many African states to protect their citizens. But African states must be wary of relationships that turn them to mere security outposts of stalemate for global powers. Bilateral or multilateral agreements must go beyond security imperatives, important as those are.

The dynamics of conflicts in Africa have economic dimensions and pretending otherwise are a dangerous delusion. Africa has the youngest, and fastest growing working age population in the world. Joblessness is the number one concern of the average citizens. Africa need agricultural productivity, manufacturing jobs, and industrialisation. Africa also has the fastest urbanisation rate in the world. We need thriving production cities, not congested feral cities teaming with jobless young men.

Therefore, in a geopolitical climate where allies are positioning themselves for ‘'near-shoring’’, and ‘‘friend-shoring’’ of critical supply chains - it should no longer be enough for African states to be only good enough for the odd military bases and petty partnership grants.

The greatest compliment that I can pay this article is that it should be framed for posterity.

It is incredibly brilliant.

The USA and China both used import substitution as part of their rise. The USA didnt just employ protectionism externally, for the first 200years of its existence it employed light INTERNA interregional protectionism and to a much heavier extent semi-fragmented capital markets with variability in monetary policy. It worked great for us.