Slightly Business Unusual is not Enough

When Muhammadu Buhari won the 2015 elections there were a lot of high expectations. Now, eight years after, those expectations have been astoundingly dashed, and the people drained of their optimism — the bar has been lowered. Despite the lofty promises of the incoming president, what many simply hope for is a government that is ‘’simply not Buhari’’.

This is not a small thing. It can be argued that a Tinubu presidency will be similar to Buhari’s, but where it differs will matter. Simply undoing many of the stupid stuff the outgoing government is doing on trade, exchange rate, agriculture, public finance, and energy can lift the mood — and unlock critically needed investment. Perhaps that is the best we can expect from the next government. But hoping that is enough to make Nigeria prosperous will not suffice.

Beyond a checklist of policy prescriptions, we need a vision of growth and prosperity for the next coming decades. It may appear that democratic election cycles and the incentives of political leaders do not agree with governance for long-term growth. But if public investment, interventions, and reforms are guided by sustainable growth, then we can lay durable foundations for future governments. I want to draw attention to two things that I think we should be mindful of in the political economy of growth.

The first is that persistent, rather than inconsistent growth, should be the goal. Secondly, certain political distortions are bad for growth — and reforms should always aim to remove them.

Persistent growth and transformation

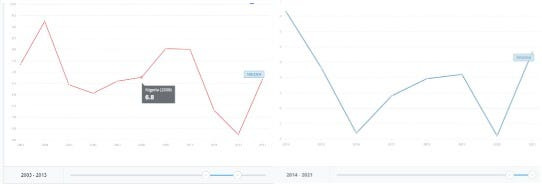

There is no need to restate so many theories of why some countries are poor and some are rich. Researchers of economic growth have found that what most of the low-income countries of today have in common is the inability to grow sustainably for an extended period. There have been periods of fast growth followed by periods of slow, zero, or even negative growth. For example, the charts above do not look particularly striking. But what they hide in plain sight is how episodic growth has been in Nigeria in the charted period.

The average GDP growth in Nigeria between 2003 and 2013 was roughly 7%, while the average GDP growth in the following decade was 1.8%. The picture is even worse for income growth (GDP per capita) which averaged roughly 4% in the 2003–2013 decade, while income dipped massively (-7%) in the decade that followed. Slightly improving the status quo might get us growing again, but can it be sustained for two decades or more?

For growth to be sustainable and prosperous — it has to be transformational. What this means is that production in the economy has to shift from low productivity to high productivity. This is not about whether to do agriculture or industry. Everything matters. What is important is that whatever role government plays, the outcome has to be for the firms in the economy to get more output than their inputs. Thinking about productivity is important because it focuses the government on the kind of public goods that firms need. It will also push the regulatory environment and bureaucratic norms towards more stability and meritocracy. Productive businesses and investors will no longer have to worry about predation in favour of those who survive on regulatory rents (see below).

One of Buhari’s favourite mantras is ‘’going back to the land’’, perhaps his agriculture drive could have been more successful if he thought more about getting ‘’more yield from the land’’.

Political distortions are bad

Nigeria’s incoming president has a bit of a reputation as an excellent dealmaker and an all-around pro-business person. Many people are excited that this pro-business orientation will be a catalyst for economic growth. However, how the political interaction with the private sector is structured will determine whether the growth will be an adrenaline rush that temporarily numbs serious injuries or diagnostic care that nurses the economy to health on the path to sustainable growth. This public-private political relationship will determine whether policies will incentivise productivity or become political distortions to long-term growth.

Economists Nathan Canen and Leonard Wantchekon define political distortion as (Page 11):

‘’….. any situation in which a special interest group can direct economic development towards its own exclusive ends rather than towards increasing general welfare. It also captures situations in which the provision of public goods, public investments, and redistribution is instead primarily motivated by the narrow political interests of office-holders, or of its political connections, rather than by considerations of public interest and general welfare.’’

As a friend of mine frequently says ‘’ It is better for governments to be pro-market than pro-business’’. The generic use of the term private sector often hides important distinctions. The private sector exists in two dimensions; (i) domestic suppliers and exporters (ii) Businesses that generate profits through regulatory access and those that profit from market competition. Despite the distinction, there are overlaps — but the point here is that often businesses have policy and public goods demand based on the space they occupy in the distinction.

Competitive firms usually demand a stable, open, and fair regulatory regime. Exporters often need quality infrastructure and relatively liberal trade policies. Navigating the different demands can be politically challenging given competing interests. But overall, allowing firms who survive on exclusive access to favourable regulation to capture policy is a political distortion and bad for long-term growth.

Nigeria faces many critical decisions in the next few months. The specific policy choices that will be made are important — but how we think about those choices and justify them will be important for future choices we make. It is going to decide whether we will transition from growth to prosperity or just to another crisis.