Reform or Routine? What Senator Abiru’s Bill Means for Nigerian Insurance

Will this bill unlock the industry's potential - or lock it out?

Insurance. Just saying the word probably makes you yawn. Few topics can empty a room faster.

So why am I bringing it up here? Well, insurance happens to be my day job. I’ve spent a few years in the industry, so when Senator Tokunbo Abiru, alongside 40 other Senators, introduced the Nigeria Insurance Industry Reform Bill 2024, it naturally caught my attention. The bill aims to repeal and replace a laundry list of outdated laws—including the Insurance Act, Marine Insurance Act, and Motor Vehicles (Third Party Insurance) Act—to provide a comprehensive legal framework for insurance in Nigeria.

At this point, I’d completely understand if you’re tempted to close this page and look for something—anything—more exciting to spend your time on. But if you’re still here and curious to know what I think after a quick read, here’s my take.

A Problem of Definitions

Nigerian legislators have a knack for drafting bills that are less than future-proof. The tendency to hard-define everything—admirable in theory—often backfires when faced with the pace of change in modern industries. A lack of technical foresight in this regard has been a recurring Achilles’ heel.

The Nigerian Insurance Industry Reform Bill (NIIRB) follows this path. It diligently categorises insurance businesses into life and non-life. So far, so conventional. It then goes a step further by listing the sub-classes—four for life and eight for non-life. But what’s with the precise numbers? Why set these categories in stone?

The trouble begins when new types of insurance emerge. Absent from this list are critical modern coverages like cyber, professional indemnity, travel, trade credit, political risk, pet, specialty insurance and several others. Risks evolve, and niche markets often prove vital for economic dynamism. By limiting the classes so rigidly, the bill risks creating a regulatory blind spot. For instance, if I launch a pet insurance company in Nigeria today, can I argue that my business falls outside regulation altogether? The rigid classification could make a strong case for it.

The rigidity here isn’t just theoretical; it’s an obstacle to innovation. By defining insurance classes this way, we risk stifling the very creativity and adaptability that industries like insurance rely on. If anything, the NIIRB should leave room for the unexpected, because in this fast-moving world, the unexpected is precisely what we should expect.

A better approach would have been to define insurance—or an insurance contract—in terms that actually capture the essence of the business: providing coverage and managing risk. It’s not rocket science, after all. If our esteemed Senators are struggling to pin down a definition, might I humbly suggest borrowing one from IFRS 17? Their definition of an insurance contract hits the nail on the head:

identifies as insurance contracts those contracts under which the entity accepts significant insurance risk from another party (the policyholder) by agreeing to compensate the policyholder if a specified uncertain future event (the insured event) adversely affects the policyholder

There are other definitional problems. What exactly does ‘adequate reinsurance arrangement’ mean in the section below?:

(5) Subject to this Bill, an insurer may be authorized to transact any new category of miscellaneous insurance business if he shows evidence of adequate reinsurance arrangement in respect of that category of insurance business and requisite capital where necessary and other conditions as may be required from time to time by the Commission.

Or risk based capital below:

15. (1) A person shall not carry on insurance business in Nigeria unless the insurer has

and maintains, while carrying on that business, a minimum capital —

(a) in the case of non-life insurance business, the higher of —

(i) ₦25,000,000,000.00, or

(ii) risk-based capital determined from time to time by the Commission.

(b) in the case of life assurance business, the higher of —

(i) ₦15,000,000,000.00, or

(ii) risk-based capital determined from time to time by the Commission.

(c) in the case of reinsurance business, the higher of —

(i) ₦45,000,000,000.00, and

(ii) risk-based capital determined from time to time by the Commission.

Once again, there’s no need to reinvent the wheel. Over the past decade, the insurance industry has endured significant regulatory evolution—think Solvency II or ICS—which have already redefined and standardised the concept of insurance capital. A Senate bill is hardly the arena to wade into the technical weeds of what constitutes an insurer’s Own Funds, for example. Perhaps it would have been wiser to steer clear of throwing around terms with definitions as fluid and ambiguous as "risk-based capital."

Capital Requirements

No Nigerian bill is complete without a hike in capital requirements. It’s almost as if Nigeria believes throwing in massive numbers is the only way to filter out the “unserious.” Under this bill, you’ll need anywhere from ₦15 billion to ₦45 billion to enter the insurance industry. But let’s pause for a moment—why do I need ₦15 billion (roughly $10 million) to start a pet insurance business? By setting the bar this high, you risk snuffing out innovation altogether. A niche insurer aiming to serve specific, underserved markets has no chance of making it past this regulatory threshold.

And once again, there’s no need to reinvent the wheel. Solvency II in the EU offers a sensible approach by taking a risk-based approach rather than arbitrary monetary thresholds. The capital required should reflect the risks being underwritten, not an aspirational number that '“sounds big”. If someone wants to sell pet insurance to the arrivistes and dilettantes of Lekki, they shouldn’t need the same capital as a provider covering nationwide travel insurance. This is precisely where the Senate should defer to regulators—let them determine capital requirements based on insurers’ actual risk profiles. Nigeria’s insurance market, still in its early stages, can’t afford to close any doors on innovation. The potential for growth and diversity in the sector is enormous, and this bill needs to reflect that.

And then there’s the cherry on top: a mere 12 months to meet these sky-high capital requirements. Why not allow a phased implementation period? Rushing this through only increases the likelihood of disruption, consolidation, and the exclusion of promising entrants. Aim for progress, not panic.

Regulator’s Role

The NIIRB has plenty to say about the role of the National Insurance Commission (NAICOM), the industry’s regulator. Armed with sweeping powers, NAICOM is tasked with issuing and revoking licenses, imposing penalties, setting capital requirements, and—at least in theory—protecting consumers.

One of NAICOM’s more perplexing responsibilities is the dual mandate of enforcing fixed capital thresholds (as discussed earlier) and managing risk-based adjustments to capital. Frankly, this is a recipe for confusion. Why not pick a lane? I’d suggest ditching the fixed capital thresholds altogether and letting the regulator focus on risk-based approaches that align with insurers' actual exposures.

The bill also requires NAICOM’s approval for any new products entering the market or structural changes to insurers' operations. Licenses will now be needed not just for insurers and reinsurers but also for brokers and loss adjusters. On the surface, this sounds reasonable, but it risks becoming a bureaucratic bottleneck. Where’s the accountability for NAICOM itself? If the commission fails to process approvals or licences within the stipulated timelines, what happens? I’d love to see the bill include penalties for regulatory delays—perhaps a ₦1 billion fine (okay, maybe a bit steep, but you get my point). With great power comes great responsibility, after all.

On consumer protection, the NIIRB talks a big game but delivers little substance. The bill lacks explicit provisions to enforce timely claim settlements—arguably the single biggest pain point for policyholders. There’s no mention of a dedicated, independent framework for resolving disputes, leaving too much discretion to NAICOM. Given that Nigeria already has a Federal Competition and Consumer Protection Commission (FCCPC), creating a separate ombudsman for insurance disputes would be unnecessary. Instead, why not explicitly grant dispute resolution powers to the FCCPC within this bill? It’s a practical solution that avoids future turf wars and strengthens consumer protection where it matters most.

The commission is empowered to monitor insurers’ financial health, demand reports, and conduct inspections, with non-compliance leading to penalties, suspension, or licence revocation. This is regulatory enforcement in its most traditional (and adversarial) form—a hallmark of Nigerian regulators. Once again, we see a law written to emphasise punishment over partnership, with no mention of collaboration or proactive engagement. It’s all stick, no carrot.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Globally, regulatory frameworks have evolved to prioritise dialogue and prevention over punishment. As examples:

Solvency II (EU): Encourages regulators to engage in continuous dialogue with insurers, focusing on risk-based assessments and preemptive measures.

Prudential Regulation Authority (UK): Adopts proactive supervision and early warning systems, working with insurers to identify risks and strengthen governance.

National Association of Insurance Commissioners (US): Implements risk-based surveillance to flag issues early and provide advisory feedback before resorting to penalties.

You get the point: a regulator’s job isn’t just to show up after something has gone wrong, throwing fines around like confetti. It’s about ensuring that issues are spotted—and solved—before they escalate. A collaborative approach helps insurers improve compliance, protects consumers, and builds trust in the system. The NIIRB, however, misses the opportunity to encourage this. A few provisions promoting early engagement, risk monitoring, and preventive dialogue would have gone a long way in aligning Nigeria’s insurance regulation with modern, global best practices.

The NIIRB is full of ambition, but ambition without clarity and accountability risks becoming a liability.

Foreign Participation

The NIIRB places significant restrictions on foreign insurers and reinsurers, especially those without a local presence or effective consolidated supervision in their home countries. While the intention is to protect the domestic market (wink), these restrictions risk sidelining the benefits of foreign expertise, capital, and innovation.

Consider this clause in the bill (emphasis mine):

Any insurer incorporated in a foreign jurisdiction or its subsidiaries which:

(a) does not have physical presence in the country where it is incorporated and licensed; and

(b) is not affiliated to any financial services group that is subject to effective consolidated supervision,

shall not operate in Nigeria and no Nigerian insurer or its subsidiary shall establish or continue any relationship with such insurer or subsidiary.

Why require a physical presence? This automatically disqualifies many insurtech companies as potential partners for Nigerian insurers. To name but a few:

Lemonade (USA): A fully digital insurer offering renters, homeowners, pet, and life insurance, operating entirely through its app and website.

Root Insurance (USA): Specialises in car insurance, using smartphone data to tailor premiums.

Cuvva (UK): Offers flexible, short-term car insurance via an app.

ZhongAn Insurance (China): China’s first online-only insurer, providing products like travel, health, and property insurance.

Wefox (Germany): A digital insurance platform offering a variety of products through its app and website.

Oscar Health (USA): A health insurance provider using technology to simplify claims and policy management.

Even if these companies don’t set up shop in Nigeria, can the industry not benefit from the technologies they’ve developed? A middle ground is possible—one that accommodates online-only players while ensuring regulatory compliance and consumer protection, which are legitimate concerns for digital insurers. Instead of blanket restrictions tied to a physical address, the bill could mandate minimum standards, such as compliance with internationally recognised regulatory frameworks (e.g., Solvency II or NAIC standards) or a proven track record of financial stability and governance.

In an era when insurance regulations are increasingly globalised—think Solvency II and IFRS 17—it makes little sense for Nigeria to isolate itself with these kinds of protectionist instincts. These restrictions risk discouraging partnerships and collaborations that are critical for integrating into the global insurance market. Instead, Nigeria risks branding itself as a regulatory fortress too troublesome for any serious foreign investor to bother with.

Summary

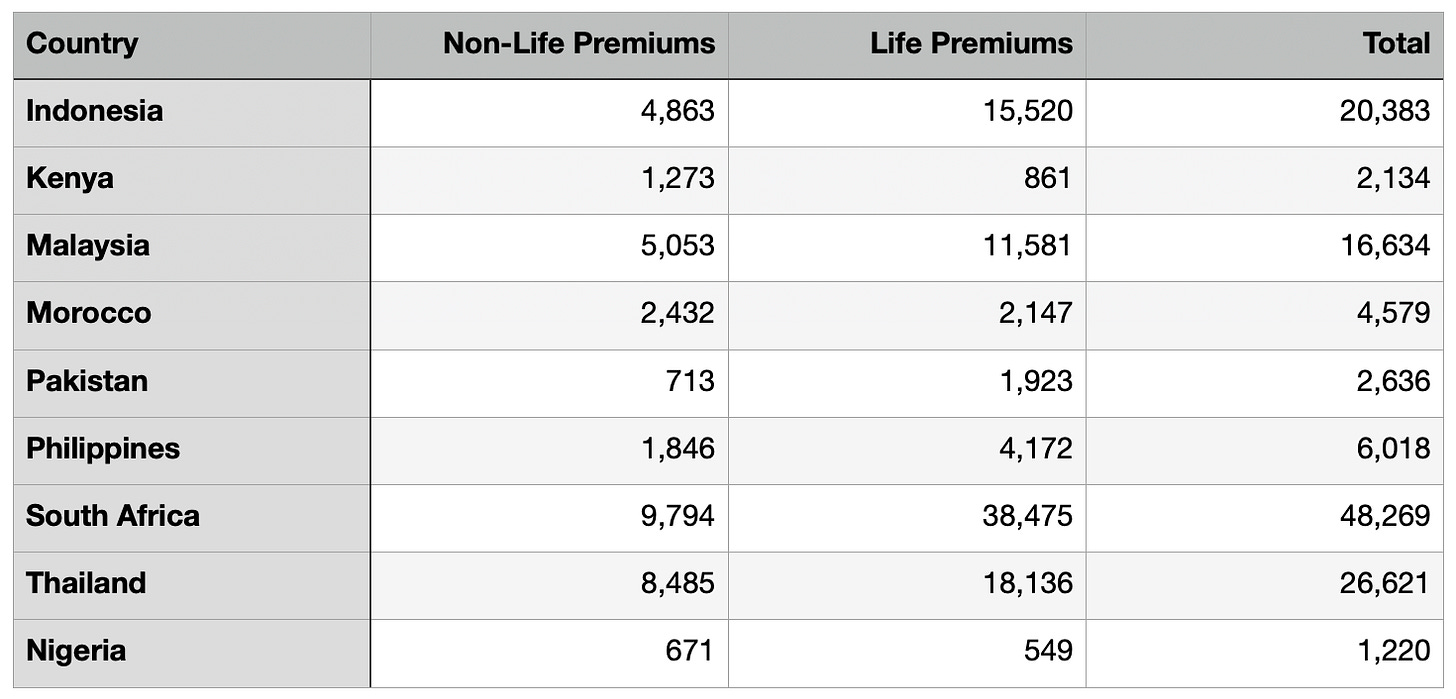

Given how these things tend to work, I fully expect the bill to pass in its current form. That would be a shame. And in a cynical way, Nigerian insurance has hardly been an interesting industry for decades. Here’s a table I put together a couple of years ago (all numbers in US$ millions):

So the bill cannot kill that which was barely alive in the first place. The real tragedy isn’t what the bill might destroy—it’s what it fails to create. This was a golden opportunity to breathe life into an industry with untapped potential.

Instead, we’re left with yet another missed chance to rewrite the story of Nigerian insurance into something worth paying attention to.

There has been a recent push by federal agencies for foreign businesses to set up shop in Nigeria. For example, the new SEC requirement mandates that crypto firms in Nigeria set up local offices and have their chief executive officer reside in the country. However, the problem is that the Nigerian Government has a terrible reputation with foreign companies. The Binance saga this year was a mess, and then the worsening insecurity, which led to the kidnapping of Fouani executives, does not inspire confidence.

Good read, Feyi. I believe it was Lead Assurance that provided a somber stat that roughly 1 in 200,000 Nigerians (or, 1,100 people) have life insurance, highlighting just how disinterested we are in paying life premiums.

That said, one would expect that this bill should, as you say, encourage more participation and collaboration in an industry in much need of support. Instead, we have raised barriers to entry with this new policy on recapitalisation and reinforced rigidity. It is the answer to the question no one asked.