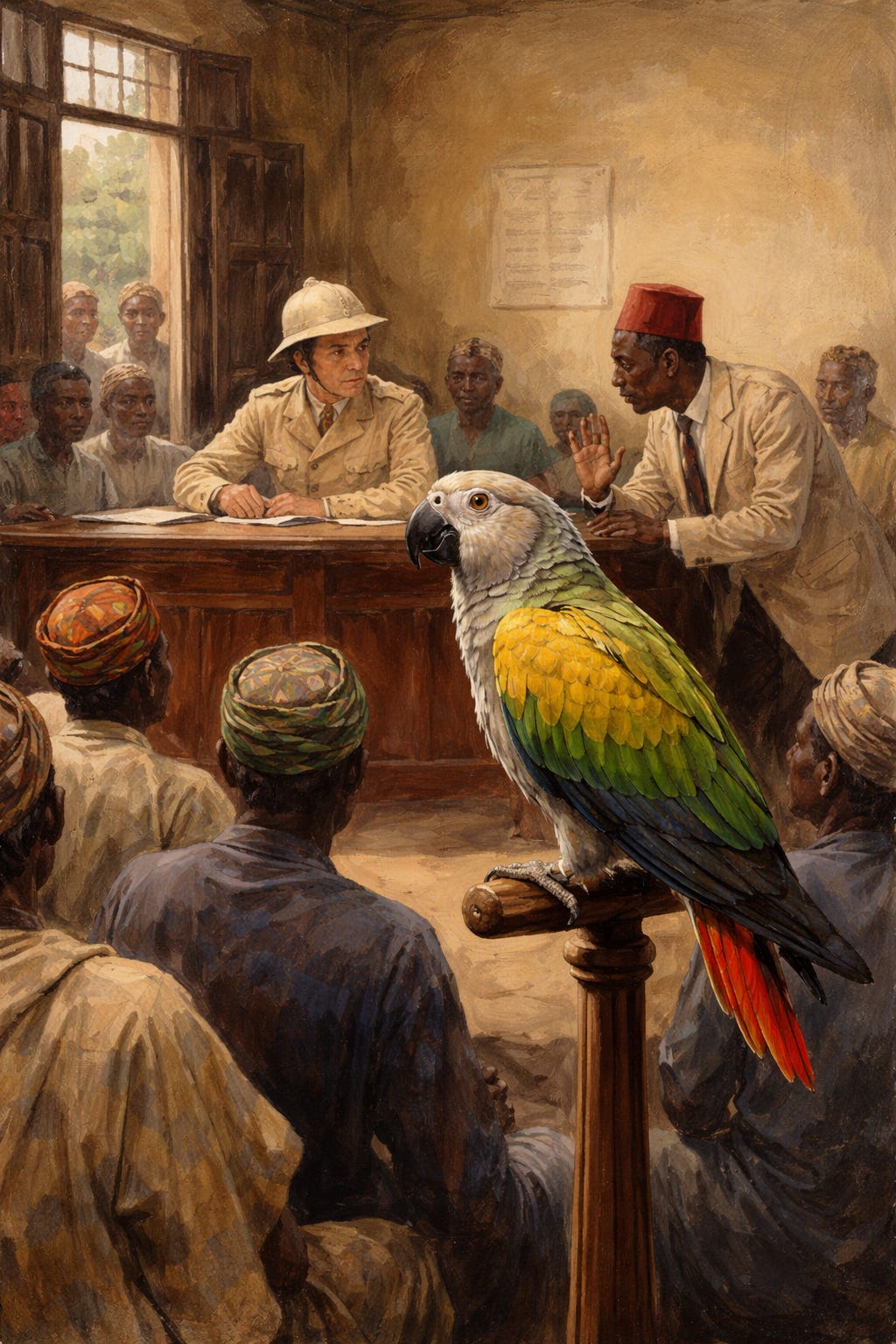

Introduction: The Parrot's Work

The Whispering Class: Interpreters as Language Brokers in Colonial Nigeria

For many years now, I have been fascinated - perhaps obsessed is the more honest word - with the role interpreters played during the colonial era in Nigeria. I had long thought that one day I might collect enough stories to make a book, but this proved rather more difficult than it sounds. The problem is that interpreters are so often unnamed in the records, leaving us with almost no insight into their lives even as their influence shaped events. They were undoubtedly powerful, and many of them parlayed that power into wealth and status that outlasted the encounters they brokered.

I have now managed to gather a sufficient number of stories to attempt the book I had in mind (I’d say I have 60-70% of what is needed). The plan is to release one chapter a month, each standing alone as a story centred on an interpreter or an event in which interpreters played a decisive role. If I do it this way, then I might commit myself to the project instead of sitting on the material I have until it is “perfect”.

Some of these stories will be familiar to readers of Nigerian history, but I want to retell them with a particular focus on language, translation, and the people who made those conversations happen. I hope you will come along for the journey.

Here is the first, introductory, chapter. It is also our first paid post on 1914 Reader. All chapters will be behind a paywall. You can take out a paid subscription here.

Working title for the book (subject to change, I have a few other ideas): The Whispering Class: Interpreters as Language Brokers in Colonial Nigeria

I had my heart set on being an interpreter or a clerk in the Native Affairs Department. At that time, a career as a civil servant was a glittering prize for an African, the highest a black man could aspire to.

— Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom

The District Officer sat behind his desk, papers stacked before him, with the settled confidence of a man who had come to believe that whatever was written down was real and whatever was not written down was not. His uniform was conspicuously clean. Across from him, perched on a wooden bench that had long since surrendered to tropical humidity, sat the accused - a local man whose face had been trained, through years of unhappy experience, into an expression of cautious neutrality. Behind him, packed into every available inch of the courtroom, were the men and women who had come to observe the spectacle: some in hope of justice, others in pursuit of gossip, and most simply for the sport of it.

Between these two worlds, as interpreter and intermediary, stood the Court Clerk. He occupied a position that no colonial regulation had ever formally described as power, but every person in that room who had lived long enough to understand how things actually worked knew the essential truth of it: in a system where two languages met and only one man controlled the crossing, he who held the words held everything. The Court Clerk, in short, was the hinge upon which the whole performance turned.

The District Officer - Nwa Bekee, as the local people called him, “child of the white man” - spoke in clipped English.

“O.K., Court Clerk,” he said, with the casual authority of a man who expected to be understood, “I would like to hear from the chief.”

The Court Clerk received this instruction like a summons from heaven. Then he turned sharply towards the gallery, scanned the crowded benches with theatrical relish, and called out into the room.

“Okey!“

The Court Messenger, delighted to be given something simple to do in a court proceeding conducted almost entirely in a language he did not understand, took up the cry with enthusiasm and flung it further back into the crowd. “Okey!“ Somewhere behind the assembled mass, a voice answered, startled. The Clerk pointed with evident satisfaction. “Puu ebea,” he barked in Igbo - ”Come out” - and the man, one Mr. Okey, unfortunate possessor of a common Igbo name (short for Okechukwu), was pulled forward into the open space of the court.

The District Officer looked up from his papers, puzzled. “What’s wrong? What’s it?”

The Court Clerk, more offended by the question than anything else, attempted to anchor the unfolding absurdity in English. “I think you say you want Okey.”

The District Officer frowned. “I said what?“

“Okey,” the Clerk repeated, as if the problem lay in the white man’s hearing.

“No. No!“ the District Officer snapped, now hearing the absurdity but trapped helplessly inside it.

The Clerk nodded vigorously. Then he leaned towards Mr. Okey and spoke rapidly in Igbo, his voice dropping into the intimate register of conspiracy. The meaning, when translated, was: the white man had ordered a goat, and the goat was to be delivered to the Court Clerk’s own house. Mr. Okey stared at him with the expression of a man who had just realised that innocence, in this particular theatre, was largely irrelevant.

“Nna anyi, gini ka m mekwara nu?“ he asked - ”What did I do?” - as someone confronting a system whose rules were being invented, before his very eyes, by the people meant to enforce them.

The crowd laughed. Some understood exactly what had happened - that the Court Clerk, having stumbled into an error, had decided with admirable speed to capitalise on it for his own private gain. Others could merely smell that something improper was occurring and wanted to enjoy it thoroughly before it turned sour.

The District Officer, oblivious to all of this, returned to his writing.

But something had already been established that no amount of paperwork would record. A small slip between English and Igbo, between “O.K.” and “Okey,” had reminded everyone present of the truth that sat behind the whole performance. The District Officer could not speak to these people without the man beside him, and that man had just used the gap between languages to extort a goat for himself. The crowd had watched it happen. The accused had watched it happen. The only person in the room who had not watched it happen was the one with the formal authority to stop it.

The Court Clerk earned ten shillings a month. But a man who controlled the words could, on a good day, extract a great deal more. And the District Officer, serene in his ignorance, would continue to believe that the paperwork in front of him was the country - when in fact, the country was happening all around him, in a language he did not understand.

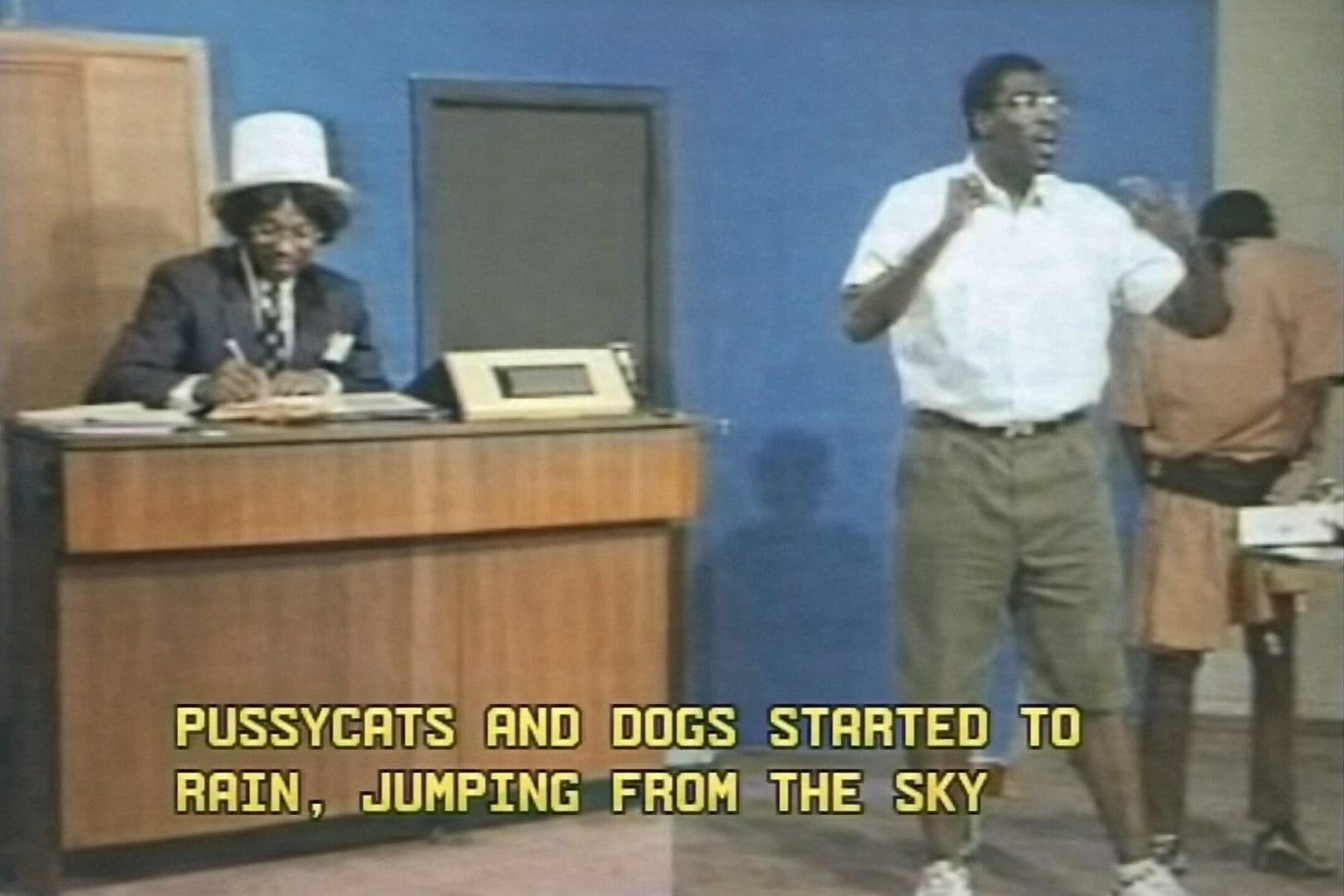

The scene comes from an episode of Icheoku, a drama series produced by the Nigerian Television Authority (NTA) in the years when that institution still possessed both the institutional muscle and the cultural self-respect to commission programming that spoke to ordinary Nigerians. It is, technically, a comedy - though like most good comedies, it delivers many a truth in jest, and some of those truths land with considerably more force than the laughter that precedes them. The name Icheoku means “Parrot” in Igbo, and the programme uses the bird as its emblem: a fitting mascot for a show whose central preoccupation is the business of repeating, translating, and - when convenient - creatively reimagining the words of others.

Most episodes were produced at the NTA’s Lagos national headquarters, with a smaller number emerging from the Enugu station in Nigeria’s southeast. The dialogue is conducted largely in Igbo, with English subtitles supplied for the benefit of those Nigerians (and they were many) who did not share the linguistic inheritance of the programme’s characters. The setting is a typical traditional Igbo community during the mid-colonial period - that interregnum when British authority had arrived but had not yet figured out what to do with itself, and when local populations had noticed the arrival but had not yet determined what, precisely, it meant for them. Each episode revolves around some domestic squabble or communal dispute that, through the logic of colonial administration, finds its way into the courtroom. The District Officer presides: earnest, foreign, and attempting with visible sincerity to dispense justice in a place whose social grammar he does not understand and whose language he cannot speak. The Court Clerk - severely handicapped in English but armed with the unshakeable confidence of the indispensable intermediary - serves as interpreter between colonial authority and a populace that remains monolingual in its own tongue.

It is a small world. But it shows the colonial encounter at its most practical and most revealing level. There are no grand speeches about civilisation, no invocations of the white man’s burden, no philosophical defences of empire. There is simply a man who wants an answer, another man who wants to survive, and a third man who gets to decide what the question becomes. Thus regarded, the courtroom is not merely a stage for the dispensation of justice; it is a theatre in which the very terms of comprehension are negotiated, manipulated, and frequently betrayed. The formal hierarchy - District Officer above Court Clerk above accused - tells one story. The actual flow of power tells quite another.

In the era when a show like Icheoku could exist, Nigerian television did not need to be subtle to be intelligent. It simply needed to be observant. And Icheoku observed, with the patience of anthropology and the timing of vaudeville, the quiet fact that interpreters are never just messengers. They are actors and editors, sometimes saboteurs, sometimes peacemakers, and always - in one way or another - shaping the world that passes through their mouths. The District Officer believed he was issuing commands. The accused believed he was receiving judgements. But the Court Clerk knew what both of them had apparently failed to grasp: that between the issuing and the receiving lay a space of almost infinite possibility, and that he alone controlled its boundaries.

This book is about those people. The parrot-men. The mouths. The brokers of language and meaning who appear on nearly every page of the official records of Nigeria’s colonial encounter and yet somehow remain, for the most part, unnamed, unseen, unremembered. In the long, messy, badly documented space where precolonial realities collided with colonial ambition - where Fulani emirs met Royal Niger Company agents, where Igbo elders faced district commissioners, where Yoruba kings negotiated with consuls - these figures turn up again and again. And yet they are almost never the subject of the story. They are simply the means by which the story was told. If you read enough of this history, you begin to ask yourself a simple question: how did any of these exchanges actually happen? How did two people who shared no common language arrive at an agreement, a treaty, a conviction, a war? The answer, invariably, is that someone stood between them. And that someone had interests of his own.

Before we return to Nigeria and its forgotten mouths, it is worth lingering on a story from elsewhere - one that illuminates the stakes of the interpreter’s craft with uncommon clarity. It is not as theatrical as a colonial court comedy. There is no studio audience, no laugh track, no Court Clerk pocketing a goat he has conjured from a misheard syllable. It is, in its own way, considerably more chilling. For it reminds us that the power to translate is also, under certain circumstances, the power to determine who lives and who dies - and that empires, for all their bureaucratic machinery, have always depended on men whose names they never bothered to record.