Institutions and Persons

Although many factors like Geography, history, culture, and trade, have been fingered as being responsible for the transformation of some previously poor countries to become relatively more prosperous — I want to focus on institutions. Some scholars have argued that ‘good institutions” is the godfather of all growth factors in the quest for economic development - but even if you disagree, the importance of institutions cannot be overemphasized. There is a common Nigerian phrase (the exact wording often varies) that the way the country can work is if we ‘’build institutions and not people’’.

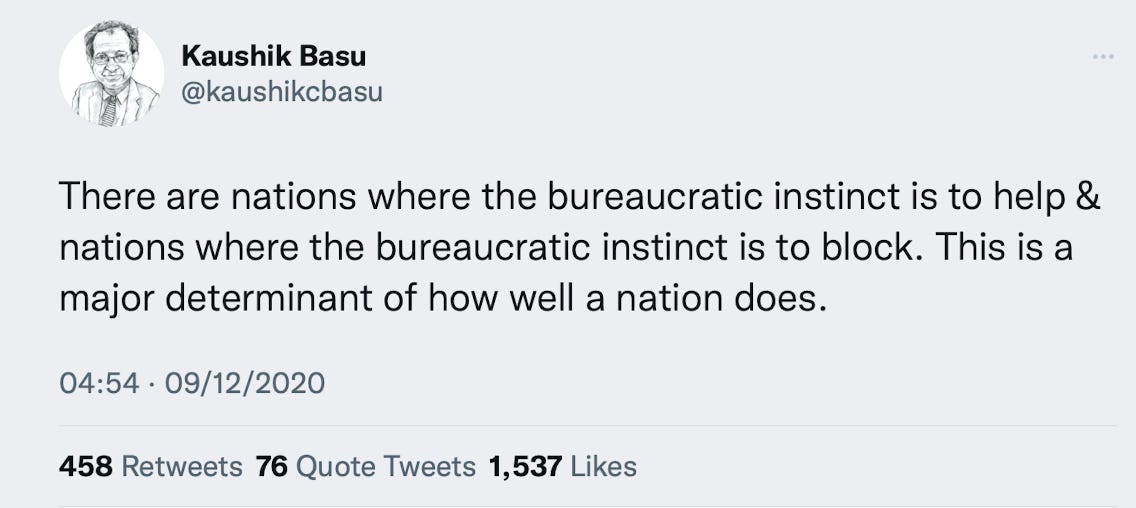

Trying to understand institutions beyond these popular platitudes is where the clarity ends. But some of the things often attributed to good institutions are a bureaucracy that delivers on its functions, transparency, and accountability in public spending, adherence to rules rather than personal discretion, and a general orientation towards the interest of the citizens rather than just the few who are connected to politicians and public officials. In short, most of us conceive of good institutions in the mode of the governments and bureaucracies of high-income democratic countries like the U.S., U.K., Western Europe, etc.

This is not different from how many scholars also think about institutions. In their popular book ‘’Why Nations Fail’’, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson argued that the difference between countries that do well and those that do not boil down to institutions. They introduced two types of institutions which they called ‘’inclusive’’ and ‘’extractive’’. Inclusive institutions are what you want your country to have — which they then define as;

‘’[Institutions] that allow and encourage participation by the great mass of people in economic activities that make the best use of their talents and skills and that enable individuals to make the choices they wish. To be inclusive, economic institutions must feature secure private property, an unbiased system of law, and a provision of public services that provides a level playing field in which people can exchange and contract; it also must permit the entry of new businesses and allow people to choose their careers.’’

As mouthful as it reads, it is a good representation of how institutions are conceived. The Nobel Prize-winning economist Douglass North described institutions succinctly as the ‘’rules of the game’’ — or as he more elaborately defined as;

‘’..the humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic and social interactions. They consist of both informal constraints (sanctions, taboos, customs, traditions, and codes of conduct), and formal rules (constitutions, laws, property rights).’’

The ABC of institutions

If we think of interactions within a society as a game, institutions are what define how the game should be played. If we structure the game to have ‘’good rules’’ like everybody must play fair and not cheat, then we will have good outcomes where the most inventive and creative players are the ones that win. On the other hand, if we create bad rules where ‘’powerful’’ players can steal the winnings of other players or beat up other players when they lose, then honest and creative players will leave the game — and it will soon be dominated by cheaters.

What A&R call inclusive institutions can be thought of as good rules in our game, and extractive institutions are free for all cheaters-dominated games. For most of us, institutions fail when they cannot guarantee good outcomes — and the way we think good outcomes can be obtained is by having good rules.

But one crucial oversight in my story so far is that institutions do not just describe the ‘’rules of the game’’. It also describes how the rules are going to be enforced, and the people who will do it. Scholars of institutions like A&R and North simply gloss over this by describing institutions in the long run. Locating a ‘’critical juncture’’ in history where countries made the right turn or their process of evolution to ‘’open access orders’’ might be important, but it is hardly useful or informative for any country living with institutional dysfunctions in 2023 and looking for a way out.

In the short term, countries have to deal with the incentives to write good rules, deciding which rules are fit for purpose, and ensure that everyone’s interests align with the enforcement of the rules. This process is messy and involves people with strongly opposing interests that cannot simply be ignored or suppressed.

Institutions as deals

The reason I started collecting my thoughts on this subject was Feyi’s recent essay for Stears (do read the whole thing). He reviewed the new book by Ms. Hadiza Bala-Usman, the former MD/CEO of Nigerian Ports Authority — where she detailed her personal journey to becoming the head of one of Nigeria’s most powerful trade institutions, and the travails of doing her job. The juice of the book is her account of the causes of her very public disagreement with the politically powerful minister of Transportation, Mr. Rotimi Amaechi. The whole affair seems to invite the ‘’institutions and not people’’ refrain, and it is easy to think such high-level personal disputes for power, influence, and rent can be avoided by good rules and transplanted best practices.

Feyi did a good job of pondering the implications of having public institutions with strategic importance for national development bogged down by personality clashes — here is the money quote;

‘’Here is a risk to economic development and a functional government that we don’t talk about enough in Nigeria — personality clashes will play a key role (maybe even fundamental) in how much any government can deliver for Nigerians. Even with the best intention in the world, a government (that is to say, the President) that does not get to grips with the interactions between its key appointees is not a government that can expect to achieve much. Even more so because a personality clash can be triggered by anything and once it starts, it is like a runaway train.’’

Institutions are shaped and empowered by the political contest and settlement that decide how political power is structured in a country. To paraphrase an interesting quote by Nigeria’s president-elect while he was campaigning — good institution is not served a la carte. A political system is not a product of the expression of preferences of equal citizens — it is often a product of bargain between the most powerful groups in society. Recognising the underlying political settlement of a country is a useful way to understand and analyse its institutions. What this means is that institutions are highly contextual and they rarely maintain static form even in the same country.

A political settlement that yields a strong and dominant leader will concentrate power in the leader — who can then shape public institutions with good rules, enforce them, and quickly arrest dysfunctional practices like personal disputes that can paralyze governance. The flip side is that a strong and dominant leader acting with little restraint on their powers can ‘’personalize’’ institutions. You can have good rules on paper but other organs of enforcement — like the judiciary — will not be empowered to act independently (for that will constrain the leader). What ensues is that institutions start to rot once the political settlement no longer supports a strong and dominant leader. An even worse outcome is that the leader ‘’breaks bad’’, ignores the rules, and turns institutions into their personal fiefdom of rent and vengeance. I think the Obasanjo era starting in 1999 fits parts of this description. Strong leadership can also favour impersonal institutions that enforce good rules without fear or favour.

I have joked privately that contrary to the expectations of many people in 2015, Nigeria got the weakest presidency since the start of the Fourth Republic (I say this with utmost sensitivity to many incidences of state-sanctioned violent abuses and killings that have happened since 2015). A lot of constitutional power resides with the executive in Nigeria, but the settlement that yielded the current ruling coalition does not favour the unfettered expression of that power — especially at the presidency. The ‘’travails’’ of the former head of the Port Authority is illustrative of my point. The former minister of Transportation is a founding member of the ruling party, who was at the time the governor of one of the richest subnational treasuries in the country. While he is certainly not bigger than the president, he is not a ‘’small boy’’ that can be pushed around. The ruling party at the time it came to power was made up of at least three distinct but very powerful groups that made up the coalition. This was even further confirmed by the visible presence of ‘’professional politicians’’ (as opposed to career technocrats) when the president finally got around to appointing a cabinet.

The political settlement in 2015 did not yield a strong and dominant leadership — rather it yielded a competitive leadership albeit a personalized one. Institutional contestation for power, attention, resources, and influence was not between the leader and the appointees — it was between multiple powerful stakeholders trying to carve out their personal rent space. Perhaps the president was prescient when he proclaimed at his inauguration that ‘’I belong to everybody and I belong to nobody’’ — a call to inaction if there ever was one.

‘’Good Enough’’ Institutions

So where to go from here? We will have a new government in a month — and as Feyi pointed out the struggle for the power to shape institutions started way before now. We the people will soon resume our complaints about how our institutions deviate from global ‘’best practices’’ and ‘’good governance’’ — all the things we expect from good institutions. We want formalized good rules and impersonal modes of enforcement. These are reasonable expectations, but demanding good governance and the incentive to supply good governance sometimes do not match. Our activism and agitations should be more targeted at the ‘’meta-institutions’’ — the political power structures and bargains that shape institutions. We need some better rules that help us write good rules (and enforce some of the good rules we already have).

It will be equally daunting for serious and competent people who find themselves in government. Trying to promote and enforce good rules without an understanding of the political bargain does not yield good outcomes. There is no smooth and straight road that leads to ‘’inclusive institutions’’, and I will humbly suggest that nobody should waste resources trying to find one. What Nigeria needs right now is transformation economic growth that makes our economy more productive, upgrades our human capital, creates jobs, and rapidly reduces poverty. Some scholars have argued that you do not necessarily need good institutions for growth, ‘’good enough’’ institutions will do. Political scientist Ang Yuen Yuen persuasively argued (using China as an example) that good institutions like ‘’property rights’’ and ‘’professional bureaucracies’’ are ‘’market-preserving’’ institutions. Low-income countries that need to create new markets and industries need ‘’market-building’’ institutions. ‘’Good enough’’ institutions will lack most of the features of good institutions.

The problem with good enough institutions is that they need to be backed by what Stefan Dercon calls a ‘’development bargain’’ — which is a commitment by the country’s elites to the pursuit of transformational economic growth and development. Chinese elites struck a development bargain in 1978 that was kept in place for four decades. Pitching a development bargain within the context of our politics must become part of the unofficial job of our technocrats.

Nigeria’s descent into collapse needs to be halted, and the people who will likely block efforts to correct course need to see that they stand to win too.