F.O.O.D: The Terrible Twins of Palm Oil

To whom much is given, nothing is to be expected

If you’ll allow me to mangle Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina Principle for a moment to state that: all F.O.O.D stories are alike but every account of F.O.O.D. fails through its own distinct form of culpability.

What I mean to say is that while every case study we have examined leads to the same particular outcome where Nigerians pay more for the product than they would normally have paid without the introduction of the distortions examined, the way we can apportion the blame for this outcome is often different. Sometimes it is a straightforward collusion between the government and a select group of “entrepreneurs” in which case, 100% of the blame is apportioned to the government. The case at hand, however, presents a different protagonist: a government whose sin is not particularly malicious intent, but profound negligence. The harm was not willed, but permitted.

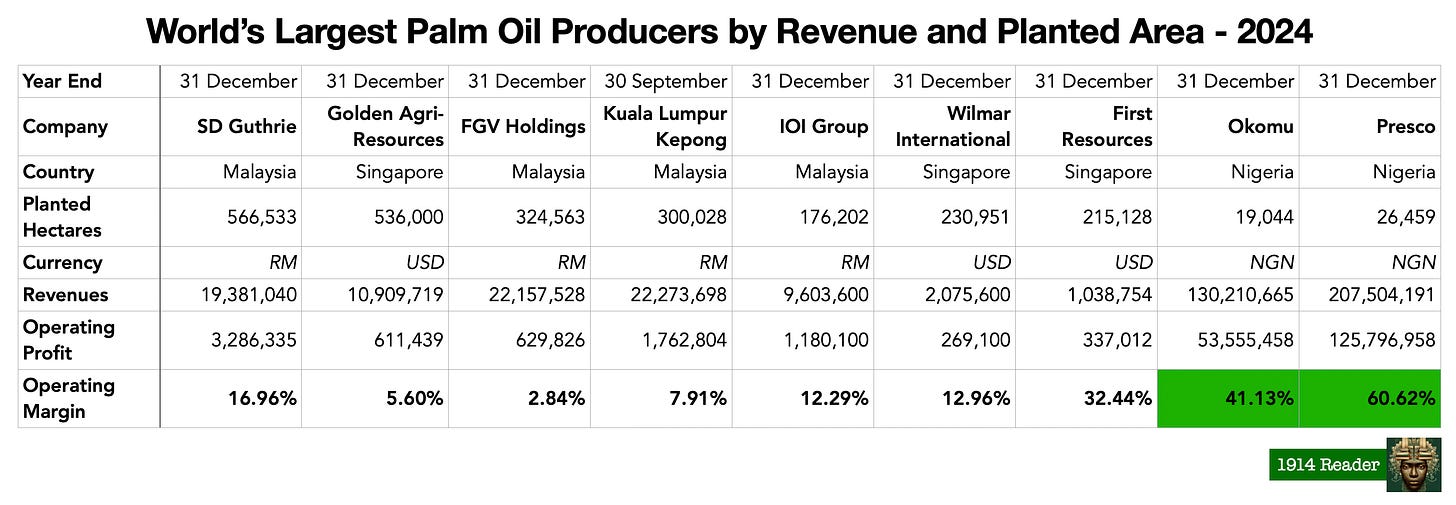

Let’s start with this table I put together:

This survey of the largest palm oil producers in the world examines cultivated land and revenue. Since the goal was to determine operating margin, revenue currency conversions were unnecessary. Wilmar, a vast conglomerate, presents a slight complication: it discloses standalone palm oil revenues but groups its operating profit with sugar. Given that a precise separation would not significantly impact the overall picture, Wilmar’s data is included as reported.

I have then tacked on the Terrible Twins of Palm Oil in Nigeria - Okomu Oil and Presco - to highlight the fact that they’re not planting much but are generating far superior margins than their counterparts abroad. How did we get here? Here it is useful to carry out a whistle stop tour of government support for palm oil since democracy returned to Nigeria in 1999.

How do I support thee? Let me count the ways

In 1999, yielding to pressure from the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the government lifted the import ban on vegetable oils, including palm oil, and instituted a 35% duty on crude palm oil (CPO). By 2001, however, succumbing to domestic industry demands, it reversed course. The import ban was reinstated, and the tariff on refined vegetable oils was raised from 35% to 60%. This protectionist measure aimed to curb imports and stimulate local production by shielding domestic processors from foreign competition. The following year, in 2002, the government launched the Presidential Initiative on Vegetable Oil Development (VODEP), a three-year programme designed to revitalise Nigeria’s oilseeds industry with a primary focus on oil palm. Its objectives included the rehabilitation of 125,000 hectares of old plantations, the replanting of 62,000 hectares of moribund estates, and the establishment of 203,000 hectares of new plantations (PDF, page 7.) It also provided generous incentives: tax holidays for 7 to 10 years and duty waivers on agricultural inputs (import duties capped at 2.5%), 50% subsidies on inputs (seedlings, fertiliser, etc.), reduced corporate tax (10%), and concessional lending rates.

The year 2008 witnessed another shift towards partial trade liberalisation, as the government once more removed the import ban on bulk crude palm oil and reinstated a 35% duty. The stated objective this time was twofold: to alleviate a domestic shortfall of over 250,000 tonnes per annum by supplying CPO to local processors, whilst still using tariffs to protect primary growers and block finished vegetable oil imports. The following year, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), in collaboration with the Federal Ministry of Agriculture, launched the Commercial Agriculture Credit Scheme (CACS). This ₦200 billion programme was designed to support commercial agriculture enterprises, including major oil palm plantations and processing projects, with loans at single-digit interest rates.

In 2012, the government introduced the Agricultural Transformation Agenda (ATA), a comprehensive programme designed to modernise the Nigerian agricultural sector. Within this framework lay a specific initiative for the palm oil value chain (PDF, section 173), which saw the Ministry of Agriculture partner with private stakeholders to distribute millions of hybrid oil palm seedlings to farmers. This effort supported new planting to replace ageing, low-yield trees and expand the total cultivated area. The initiative aimed to boost productivity and production, create employment, and ultimately regain national self-sufficiency, thereby reducing a palm oil supply deficit that had grown to approximately 600,000 tonnes per year.

In 2015 came the infamous list of 41 banned items where the CBN announced that those items would no longer be eligible for foreign exchange at the official rate. With refined oils on the list, it meant that importers of palm oil, palm kernel oil and vegetable oils could no longer obtain USD at the cheaper official rate, effectively curbing such imports (unless financed at costly parallel-market rates.) This policy, alongside earlier tariffs, significantly pushed manufacturers to source palm oil domestically. A few years later, Business Day wrote that “palm oil producers benefited from the blacklisting of some 41 items including oil palm by the Central Bank of Nigeria in 2016, when dollar shortage fostered local demand of the agro-product and the fifteen months border closure policy.” Yes, the 2019 border closure can be counted as government support for the industry as well. Any attempt to allow any kind of palm oil imports was met with howls of protest by the palm oil cabal, POFON (Plantation Owners Forum of Nigeria.)

The border closure of 2019 was accompanied by another significant intervention: the launch of the Central Bank of Nigeria’s (CBN) dedicated Oil Palm Development Initiative. As part of its broader Anchor Borrowers’ Programme, the Bank established a dedicated fund - with over ₦30 billion committed within months - to finance the expansion of oil palm cultivation. It convened meetings with 14 state governors to secure vast tracts of land for new plantations, with the ambitious goal of cultivating an additional 1.4 million hectares within three years. Under this scheme, states pledged approximately 100,000 hectares each, while private investors were matched with these land parcels and received CBN financing. The stated objective was to bridge an estimated 1.25 million metric tonne annual supply gap (a figure that had grown steadily despite previous government efforts), conserve about $500 million in foreign exchange spent on imports, generate employment, and ultimately position Nigeria among the world’s top three palm oil producers. A report from three years ago said that “a total sum of N45.03 billion had been disbursed by the bank to stakeholders in the oil palm industry including the major producers, Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) and smallholders’ operators, to cultivate about 31, 442 hectares to grow the commodity.”

This federal support was mirrored by significant initiatives at the state level. For instance, in 2019, Edo State launched its Oil Palm Programme (ESOPP), allocating over 120,000 hectares to major agribusinesses like Dufil Prima Foods to establish new plantations and mills. Similarly, in 2021, Ondo State introduced its “Red Gold” project, designating vast areas of forest reserve for development by private investors using Central Bank financing, with companies like SAO Agro-Allied commencing cultivation.

The late 2023 repeal of the eight-year ban on 41 items, a component of the CBN’s foreign exchange reforms, did not signal a market opening for palm oil. Importing refined palm oil remains prohibited under Nigeria’s Import Prohibition List, a legal statute that imposes an outright ban. In practice, this creates a de facto monopoly for domestic refiners, who are shielded from foreign competition in finished products. The sole legal import is crude palm oil (CPO), intended for industrial processing by local refineries, and even this is heavily managed through tariffs and quotas. Government bodies like Customs and NAFDAC rigorously enforce these rules at the borders. Attempts by a few companies to circumvent this regime - for instance, by lobbying for duty-free CPO under ECOWAS provisions - have been consistently rejected following pressure from local industry associations. Consequently, the entire regulatory framework is designed to insulate the local market, guaranteeing a protected environment for domestic producers and investors in import substitution.

I’ve surely missed out some other support programmes. But I should think that all of the above makes the case that the government has consistently offered support and protection for palm oil in a bid to reclaim some lost glory or the other. This is not to exonerate the government from promulgating foolish policies with predictable outcomes, but to shine a light on those who have benefitted from these policies and given nothing back in return.

The Terrible Twins

Before we get into the numbers, the first thing I will like to say to these two companies is to find some shame. These are very highly profitable companies, protected from any external threats by years of favourable government policies, with Presco alone having a market capitalisation of more than a billion dollars, and yet I can tell you their annual reports and accounts are some of the ugliest things I have ever set my eyes on. As someone who has examined thousands of annual reports, I can attest that these documents fail to meet the standards one would expect from institutions of their standing.

When you open Okomu’s 2024 annual report, on the very second page, you are confronted with this eyesore:

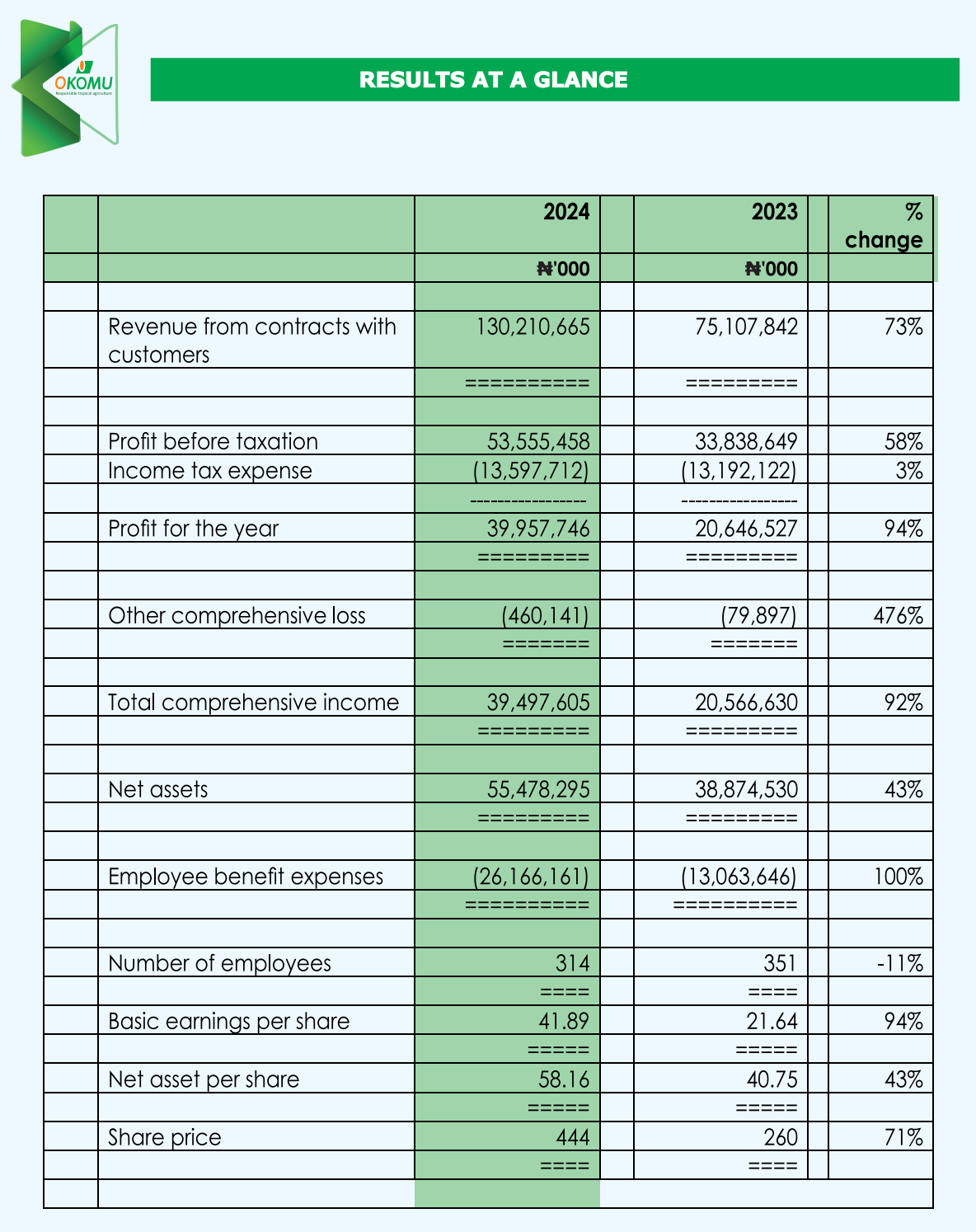

The bottle on the right looks like it suffered a near fatal accident before the “photoshoot”. This is what the company confidently puts out as what it produces and earns fat margins on. It is almost like taunting its readers. The rest of the accounts look like they were stained by palm oil during printing. The actual numbers were just dumped in the accounts from Microsoft Excel:

Presco is only marginally better. I appeal to both companies to please find some shame. At least pretend like you’re actually doing something to earn those margins.

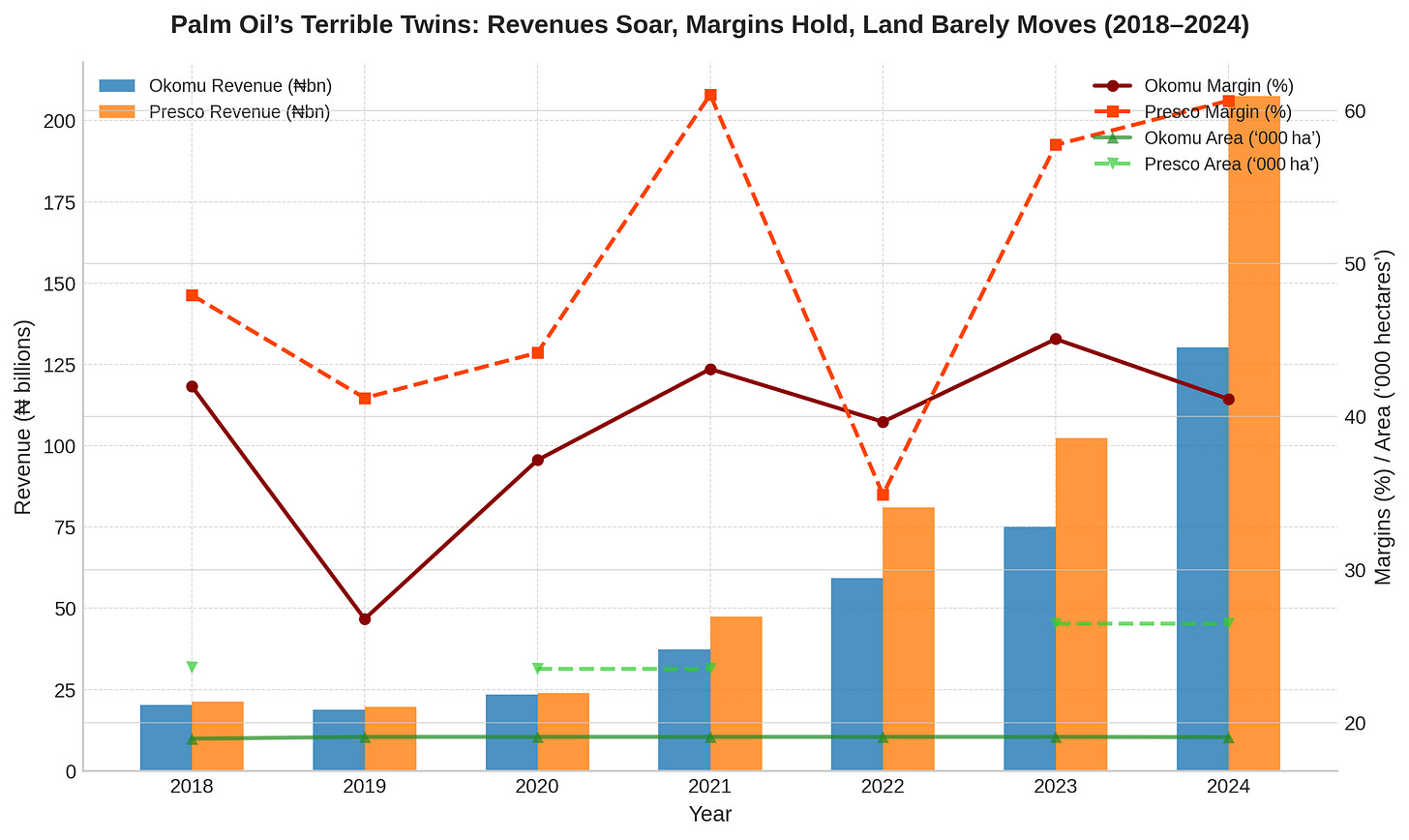

But enough about aesthetics. I went as far back as 2018 and pulled the revenues, operating profits and area under cultivation for the Terrible Twins so see how they’ve been doing over the years:

Apologies for the dense looking chart which is trying to squeeze in three key pieces of information. The most straightforward is revenue, which has demonstrated steady growth with Presco gradually widening its lead over Okomu. Given the domestic shortfall in crude palm oil, the notable revenue surge from 2023 onward can be partially attributed to currency devaluation: their combined annual revenue leapt from N140 billion in 2022 to N338 billion in 2024 (that is, they put up their prices significantly.)

The second metric, operating margin, reveals a history of sustained and exceptional profitability. While the chart may suggest fluctuation, the underlying reality is one of consistently high returns. In 2024, Presco achieved a remarkable operating margin of 61% - a startling figure for a company producing a basic food staple, not some AI-enabled palm oil or proprietary technology. Okomu’s performance has been similarly robust, peaking at 45% in 2023 and settling at a still-impressive 41% in 2024. Its margins have dipped below 30% only once in recent years (2019), demonstrating their enduring strength.

The final, and most telling, metric is the companies’ reported cultivated land area. Okomu’s figures demonstrate stagnation: from 18,946 hectares in 2018, it reported a minimal increase to 19,060 the following year - a number that remained unchanged until a reduction to 19,044 in 2024. Presco’s reporting (I couldn’t find numbers for 2019 and 2022. As I said, their disclosures are terrible) shows a marginal increase from 23,592 hectares in 2018 to 26,459 in 2024. When viewed against the first chart in this analysis, these numbers are a mere fraction of the landholdings of their global peers. These laughable numbers underscore the profound disconnect between the CBN’s ambitious 2019 goal to cultivate an additional 1.4 million hectares and the on-ground reality of Nigeria’s leading producers.

Yesterday’s price is not today’s price

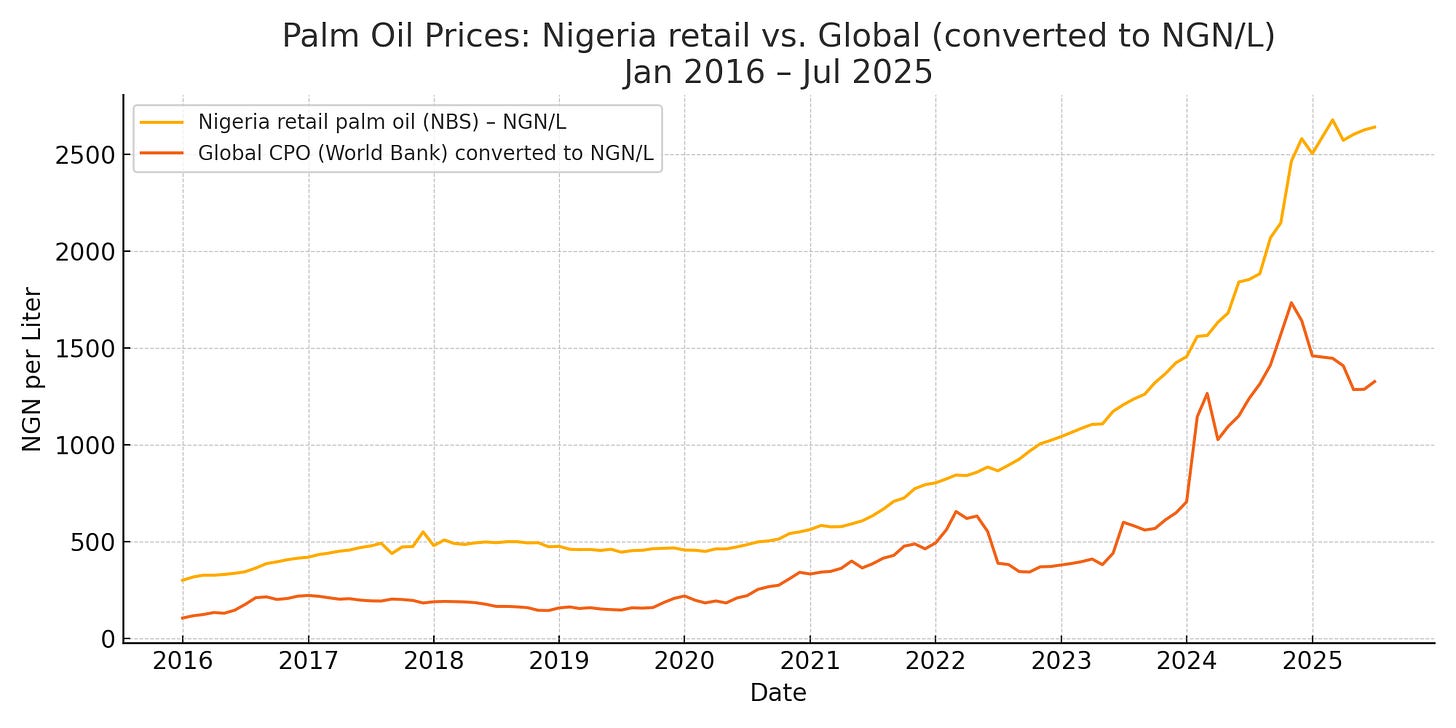

Despite very minimal new planting, negligible research and development, and a lack of innovation even in basic branding, these companies maintain consistently high profit margins. The explanation, a recurring theme in the F.O.O.D series, is their immense pricing power. To demonstrate this, we can turn to consumer price data from the Nigeria Bureau of Statistics (NBS), which tracks the cost of a one-litre bottle of palm oil from January 2016 to the present. By comparing this domestic trend against the global benchmark for crude palm oil - the US dollar per metric tonne price from the World Bank Pink Sheet - the nature of their advantage becomes evident.

To compare both prices, I first established product comparability by treating the NBS data as representing crude palm oil at the consumer level. I then converted the Pink Sheet’s price per metric tonne into a price per litre using the standard density of crude palm oil, and for the currency conversion, I used the monthly average of the CBN’s official exchange rate. No adjustments were made for freight, taxes, or retail margins, as the goal was to analyse relative price movements over time, not to calculate an exact landed cost for importers. The refining yield figures were a separate consideration, used only to estimate the volume of refined oil produced from crude. You can inspect my data here.

Here’s what it looks like:

At every point in the series, local prices have been higher than international prices. Even worse, when international prices drop, local prices don’t drop. By the end of the series in July 2025, local prices are N2,642 per litre with international prices N1,328 per litre, almost exactly double. This has been the story for as long as the Nigerian government has been “protecting” the local palm oil industry. In 2001, the United States Department of Agriculture FAS report had this to say about the Nigerian palm oil market:

Nevertheless, domestic vegetable oil prices remain well above world market levels. The world market price for crude palm oil fell from $700 per ton in 1999 to less than $300 per ton at present while domestic prices fell from about $800 per ton to $550 per ton over the same period. Local processors complain that lower-priced imports have adversely affected demand for their products and their profit margins.

Later, in a report on Sub-Saharan African import duties, the Malaysian Palm Oil Council (MPOC) almost mockingly singled out Nigeria, writing:

The first ban on the importation of vegetable oil was implemented in 1986. In 1995, there was a replacement of existing ban with high import duty by the federal government. In the year 2002 – 2008, the Nigerian federal government again imposed a total ban on the import of vegetable oil. The government of Nigeria removed the total import ban on crude palm oil in December 2008 but an import duty of 35% was put in place instead. However, this duty applies to edible oil imported from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) countries. Packed vegetable oil products imports remain banned.

Although the policy has managed to increase the prices of locally produced palm oil, it has not been successful in attracting new investment in large oil palm plantations. In ten year period between 2010-2019 oil palm plantations’ area in Nigeria only increased by 110,000 hectares from 430,000 hectares in 2009 to 540,000 hectares last year. Palm oil production increased from 780,000 MT to 1,220,000 MT during that period, while demand has increased from 1,630,000 MT to 2,570,000 MT. As a result, Nigeria has continued to increase its imports from Malaysia, Indonesia, and other neighbouring West African countries.

You can almost hear the report’s author saying “hope these guys stay stupid with their policies, so we can keep selling palm oil to them”. Given how long ago this report was written, you can say their hopes were not unfounded.

Conclusion

In Patrick McGee’s excellent book, Apple In China, a chapter details “Project Purple” - Apple’s codename for its clandestine mission to build the first iPhone. This endeavour required more than reimagining mass manufacturing; it necessitated designing the entire production process from the ground up with untested ideas. Since no contract manufacturer possessed the requisite experience, Apple faced a unique challenge. This ultimately worked to Foxconn’s advantage. While not the most skilled manufacturer considered, Foxconn distinguished itself through its willingness and hunger to learn. McGee notes, “So Foxconn’s ignorance was, in a way, a plus, coupled with its deep ambition to learn and proven ability to scale.” Apple engineered everything from scratch, from the specialised machinery to the factory floor layout, while parts were sourced to entirely new specifications - the touchscreen being a particularly complex hurdle (epitomised by the story of Zhou Qunfei, one of my favourites.) Only after these foundational challenges were solved could the “easy part” - manufacturing 10,000 iPhones daily in a single factory - commence in earnest.

It is a now well-established fact that F.O.O.D. beneficiaries, through their malign alliances with the government, secure outsize profits by artificially inflating the prices Nigerians pay. Yet, a more profound and, to my mind, more painful aspect of this dynamic exists. A significant portion of a society’s practical knowledge resides within its companies. The specific production knowledge that Apple developed for the iPhone in China, for instance, could not have been acquired in any American university. Although Foxconn would later leverage this hard-won expertise to manufacture Android phones for others, that knowledge was, at the outset, entirely novel and concentrated within that unique partnership. This illustrates what is lost: when a country’s industrial policy stifles genuine innovation and learning by blunting market mechanisms and feedback, it forfeits the chance to build and disperse such valuable knowledge at home.

A robust market mechanism is essential for generating the specific knowledge that drives industrial progress. Without it, companies cannot develop this crucial understanding, and the nation as a whole is deprived of what they might have learned. The reality is that Nigeria has failed to cultivate meaningful expertise in palm oil production even as the government lavishes support on the industry. The primary reason lies with the protected beneficiaries of government policy who, to be blunt, are fundamentally deficient in the core competencies of their industry. Their proficiency lies in extracting outsize profits from a captive market and distributing lavish dividends to shareholders. As the evidence shows, beyond this simple task of rent-seeking - transferring wealth from Nigerians who have no alternative - these entities are otherwise entirely stagnant.

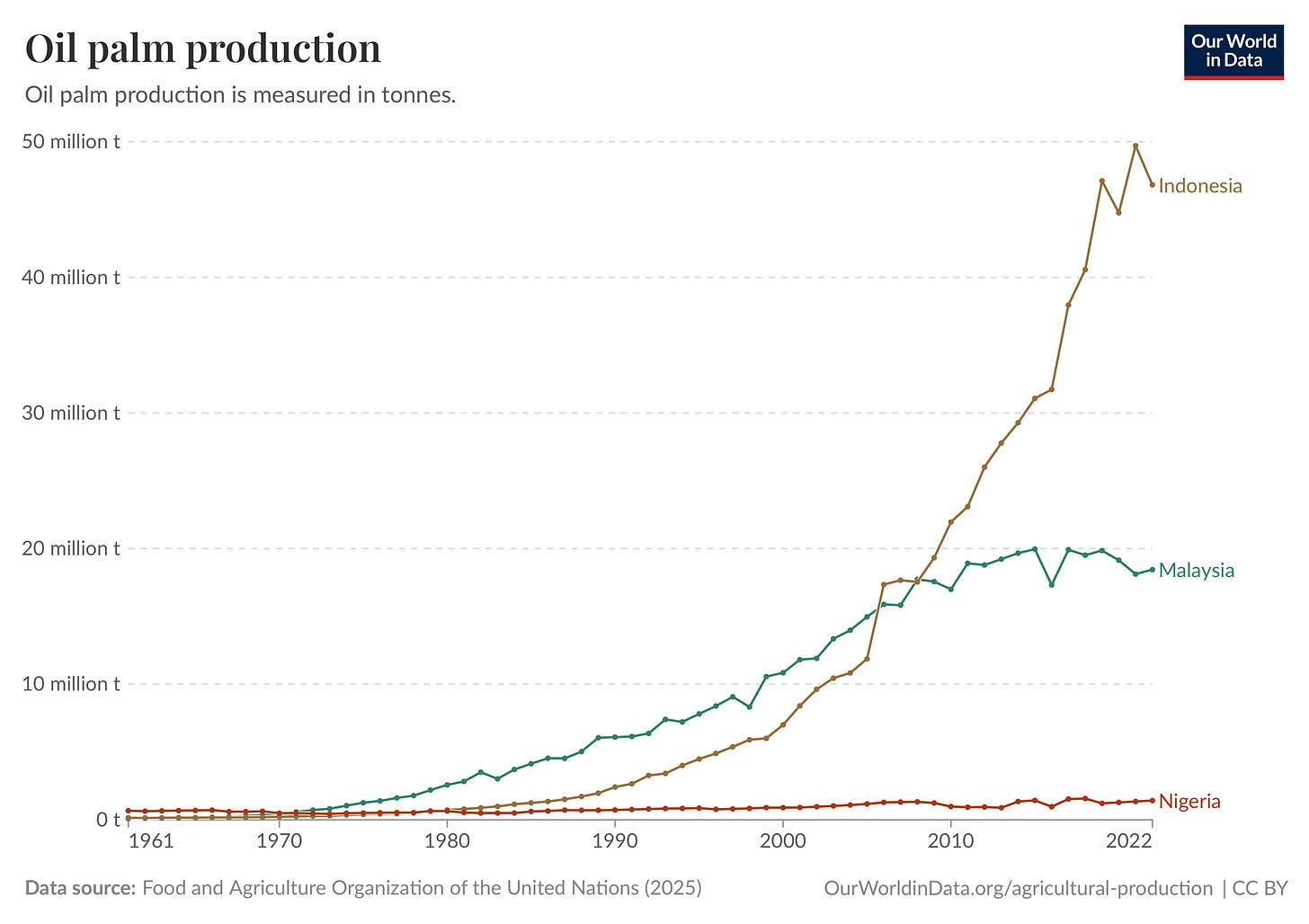

One often encounters the twin tales of Nigeria’s lost dominance in the palm oil trade and the notion that Malaysia “stole” its founding samples. This latter claim is frequently presented as an original sin, rather than a common practice in global crop development. The reality looks more like this:

Nigeria got handed a historical head start, pivoting to palm oil following the abolition of the slave trade, yet proceeded to squander this inheritance. A chart showing decline like this should compel policymakers to confront a fundamental question: how can companies achieve such extraordinary profitability within an environment of stagnation? Such easy profits are the hallmark of a distorted system. Only by completely blunting the mechanisms of a competitive market can such prosperity be extracted from outright failure.

The government might persist in heaping protections and incentives upon the palm oil industry, allowing itself to be captive to producer interests that vehemently resist any reduction of their unearned privileges. It may continue to neglect its fundamental duty to measure success by the tangible benefits delivered to Nigerian consumers. And in a vain pursuit of national glory, it might further blunt the market mechanisms essential for translating its support into genuine progress.

Yet, for as long as it pursues this course, Nigeria will consign itself to a fate of perpetual stagnation in this sector - a palm oil know-nothing among its peer nations - and a profound failure to cultivate the genuine expertise that a competitive market demands. This is not merely an opinion, but the inevitable consequence of the choices being made. I don’t make the rules.

I think you might just write a book on this F.O.O.D series coz this is just too revealing..

Solid 💯

Excellent and depressing writing, as always.