Data of the day

Nigeria is due to get an updated Migration in Nigeria: A Country Profile (opens as a PDF in Google Drive) report from the International Organisation of Migration (IOM) this year after the last one released in 2014 (it is contingent on the census being completed).

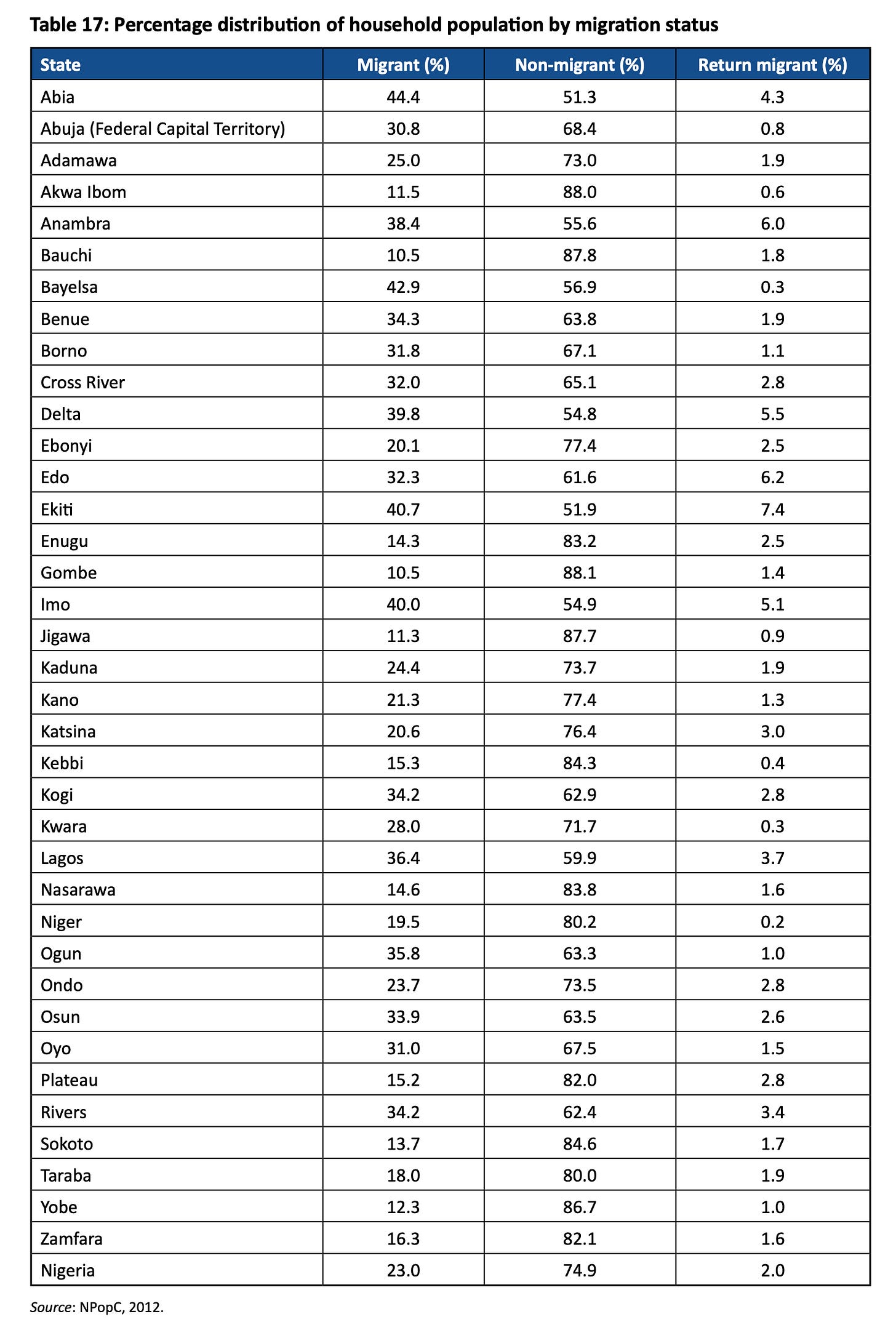

This table from the previous one is one I found interesting while discussing it with a friend:

Here is how the report defines an internal migrant:

The Internal Migration Survey (NPopC, 2012) defines a migrant as a person who has lived in another LGA for at least 6 months in the past 10 years. A return migrant is a person who has moved from the current LGA of residence in the past 10 years to live in another LGA for at least 6 months before returning to the LGA. A non-migrant is a person who has not changed residence in the past 10 years.

Now tell me that data doesn’t surprise you.

In other words this can be a proxy for the rate of internal dynamism in a country. For all that economists and development experts might say, it remains a sobering reality that the best way for people to improve their lives is simply to leave where they are and go elsewhere in search of better opportunities. We tend to mostly focus on people who leave the country altogether but where people are moving to and from within Nigeria often tells a more revealing story.

Here’s an exchange discussing the same dynamic in the US where economists watch the data on internal mobility very closely:

Beckworth: Okay. Across the interstate mobility is declined?

Cowen: That’s right. Yes. It’s gone down by around 50%. There’s a number of factors. Some of them are good, of course. Moving’s a pain in the neck and if you don’t have to move, there’s a lot to be said for that. Some of it I think is the internet and cheaper travel that you learn earlier on in your life where you’d like to live and then you just go there. Some of it is just the economy is more services and less manufacturing. So the notion you moved from Mississippi to Detroit to work in an auto plant, that’s an out of date story.

Cowen: If you’re a dentist, the incentive to move from Columbus, Ohio to Denver, Colorado, it’s not really that great, same job, maybe roughly the same level of pay. So there’s a sameness that set in to the economic geography of this country. And again, that makes life easier for us. I’m not trying to say it’s all bad, but it lowers dynamism. These labor markets adjust more slowly. Even though you’d think like, “Oh my goodness, we have LinkedIn, we have Google. People will now get new jobs again so much quicker than in the bad old days.”

Cowen: But you look at the data and not true as you know, coming out of recessions, we’ve had pretty sluggish labor market adjustments and you can’t blame it all on minimum wage or unemployment benefits. It’s some of it, but labor markets as a whole if not really gotten more dynamic. And we’re just more set in place in physical space and this contrast between information space and physical space is one of the underlying themes of the book.

Beckworth: Yeah, that was an interesting way of framing this discussion, information space versus physical space. Now, on the question again of interstate mobility, people not moving across the country as frequently as they used to. That was a little surprising to me because you hear the standard stories, I did going to school, even when I was an instructor, as a professor. There’s a standard story is that, look, this day and age, you will not stay at one job very long or grandparents may, maybe your parents, but you’ll be moving back and forth, back and forth. But that’s a myth or at least not as true as it used to be.

Hopefully Nigeria gets round to its census this year and we can have a better idea of what’s going on in the country.