Cementing Aspirations: Upgrading from Concrete Dreams

Regular readers of 1914 Reader will know that a single piece is usually not the last word on an interesting subject. To be fair, I have been the biggest beneficiary of biting off an existing piece. That’s because I am the least inventive of our duo. But do not despair, like the subject of the foregoing piece, I am going through an upgrading. So, bear with me.

Two weeks ago, Feyi Fawehinmi wrote a thoughtful essay on an observation he had from reading Ed Conway’s new book. The basic idea is that a deliberate government policy to create a domestic cement industry has not led to any transfer of skills in 20 years — despite the technology and process of making cement being thousands of years old. However, in that span, Nigeria’s cement industry has minted at least two billionaires (in dollars), but there is very little evidence that their success has contributed to Nigeria’s development in any significant way.

On the surface, it is easy to dismiss Feyi’s observation as pointless griping. After all, there is a cement industry that produces cement and employs people. So, aren’t we just a couple of bloggers hating on billionaires by asking them to carry the problems of Nigeria on their heads? The first underlying point he was making is that the emergence of the cement industry was a government industrial policy — hence the ‘success’ in this case should be measured by how it meets developmental objectives. Secondly, if the cement industry has not improved its domestic production capability in the last twenty years, then it is reasonable to conclude that it has failed to contribute to Nigeria’s development. The real question is how has it failed, and why did this failure persist?

The Catch in Catch-up Growth

One of the core ideas in economic development is the concept of ‘catch-up growth’. The simplified explanation of it is that poorer countries can grow faster, and catch-up with richer countries because they do not need to invent new technology, they can just import existing technology and know-how. So, if your country wants to industrialise and grow, then you do not need to invent your way of making cement or automobiles. Public or private firms in your economy can start cement or automobile production by following the current process and technology of how it is done elsewhere.

But there is a catch in catch-up growth. Besides the constraints of importing technology and know-how — like geography, culture, human capital, and institutions — the economic benefits of successfully importing technology are not static. For example, if your firm started with a low capability in making cement 20 years ago, the best way your firm can be productive is for you to increase your capability over that period. It is possible to be profitable without increasing capability — all it takes is to find a political arrangement that keeps other more capable firms from competing with you, thus giving you a captive market. If we scale this description to industry and country level, then it is easy to see why it is problematic. When a country is dominated by firms that do not increase their capabilities, then innovation and productivity will be slow or static. And catch-up growth and prosperity will not happen.

Firms increase their capabilities by upgrading. In response to Feyi’s piece, one of our brilliant guest bloggers drove home the point that ‘constant industry upgrading is how a country develops’. Upgrading happens when firms learn new and better ways to make their products, hence raising product quality — or when firms learn to make other complex and high-value products. The guest blog cited the example of Hyundai, one of the early and largest chaebols during South Korea’s reform era. Many of us know Hyundai as a manufacturer of automobiles today, but it started its industrial journey as a construction company. This is not limited to Korean chaebols alone, historically and across developed economies, industrial upgrading and economic development are strongly correlated.

What drives Upgrading?

I think what we need to understand is what drives upgrading. Understanding this can allow us to speculate on the possible reasons why industrial policy in Nigeria does not lead to upgrading, and how we might change that.

Eric Veerhoogen, an economist and one of the foremost researchers on industrial development, conducted a recent review of the research on upgrading. The conclusion is that:

Increases in sales to developed-country consumers, either directly through exports or indirectly through supplying in value chains with developed-country end-consumers, appear to robustly generate increases in the average quality of goods produced. Evidence is accumulating that they generate increases in productivity as well. Increased availability of high-quality inputs also appears to promote upgrading.

It is not clear that developing-country firms are making mistakes by not upgrading, given the differences in market conditions they face and their existing levels of know-how. But there is growing evidence that tailored, intensive consulting interventions can improve firm performance. Developing-country firms appear to be constrained by a lack of know-how. A key challenge, perhaps the key challenge, in promoting upgrading is to promote learning by firms.

The incentives for upgrading can come from both internal and external conditions — or sometimes a serendipitous mix of the two. Setting an export agenda for industrial policy is a good way to incentivize learning for domestic firms — exporting to rich economies is also a good incentive for quality upgrades. Trade policies can also be an external source of incentive for upgrading. A very cool paper by Professor Pamela Medina on the Peruvian apparel industry illustrates how import competition can yield positive outcomes:

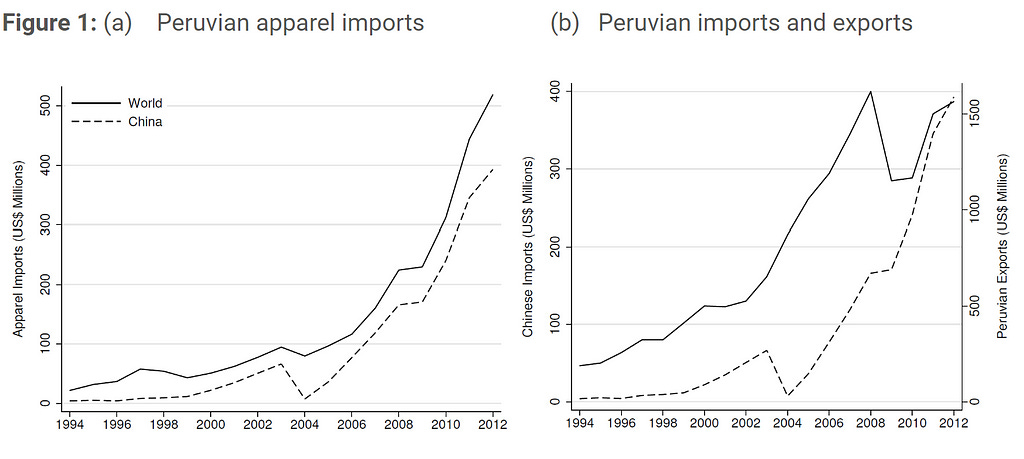

Import competition intensified for the Peruvian apparel industry after China joined the WTO in 2001. Before China entered the WTO, most of the clothes sold in Peru were made by Peruvian firms. As Panel (a) of Figure 1 shows, in just one decade, China inundated the domestic economy with cheaper clothing. As a result, Peruvian firms lost substantial domestic market share, and by 2011, half of the clothes sold in the country were of Chinese origin. The situation was no different in Peru’s most prominent export destinations: Chinese import competition also increased in the United States and other developed countries. This represented a massive negative shock for Peruvian producers.

Consequently, the Peruvian apparel industry experienced a transformation, but did not take the bad turn everyone expected. Surprisingly, while Peruvian firms lost substantial domestic market share, the industry kept afloat, mostly thanks to unprecedented export growth (Panel (b) of Figure 1). The rise was such that between 2000 and 2008, the share of total industry sales that were exports rose from 56% to 71%. Interestingly, most of this export growth happened in garments made of a very high-quality material, the native Peruvian pima cotton. Peruvian firms were changing their product bundle towards these high-quality cotton garments, whether they were frequent exporters or had just started to sell abroad.

Professor Medina was also careful to note that this transition would have had a reduced positive effect without access to quality inputs and a rich external market for Peruvian apparel producers. This means that despite the lack of domestic control on some international trade arrangements, there is room for local policy support for firms in accessing inputs and strategic overseas markets.

Daewoo in Bangladesh

The origin of the garment industry in Bangladesh provides another interesting example of external trade incentives for learning and upgrading. Daewoo was South Korea’s second-largest chaebol (after Hyundai of course), and it started as a textile manufacturer before growing into a multi-billion-dollar conglomerate with divisions for automobile, shipbuilding, and electronics. But before its eventual collapse due to excessive debts during the Asian Financial Crisis in the late 90s — Daewoo helped start a garment industry in Bangladesh. As summarized in this article, the process was kickstarted by pressures from U.S trade policy:

Though credit for social development often goes to large civil society organisations, Bangladesh’s transformation has been largely driven by the ready-made garments (RMG) sector. From 1974, the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA) set quotas on garment exports from Asia’s newly industrialising countries into the US market. Entrepreneurs from quota-restricted countries like South Korea began looking at options for ‘quota hopping’.

Daewoo was an early entrant in Bangladesh and set up a joint venture with Desh Garments in 1977. 130 supervisors and managers were trained at a state-of-the-art plant in South Korea. Within a year, 115 of the 130 left Desh to work at newly formed RMG companies in Bangladesh.

After the quota regime ended in 2005, Bangladesh stepped up its garment exports — and even outcompeted India and China. Today the Bangladesh garment industry is an export and employment juggernaut, and the country has ambitions to follow the example of Vietnam by upgrading to more complex products like electronics. This shows that with the right leadership and partnerships, negative shocks from trade agreements or geopolitical events can also provide positive pressures and opportunities.

What Nigeria needs to learn here is that government industrial policy and investment must pay their ‘’dividends of development’’ in productivity, jobs, and economic growth. An industry that has failed to improve its capabilities over an extended period should no longer enjoy generous policy support.

Even if you protect an industry from foreign competition, a vigorous domestic competitive environment that incentivises learning and accumulation of new capabilities should be the default policy intuition.

Cementing Aspirations: Upgrading from Concrete Dreams was originally published in 1914 Reader on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.