Après Chikwe, le Déluge? The Fragility of Progress in Nigeria

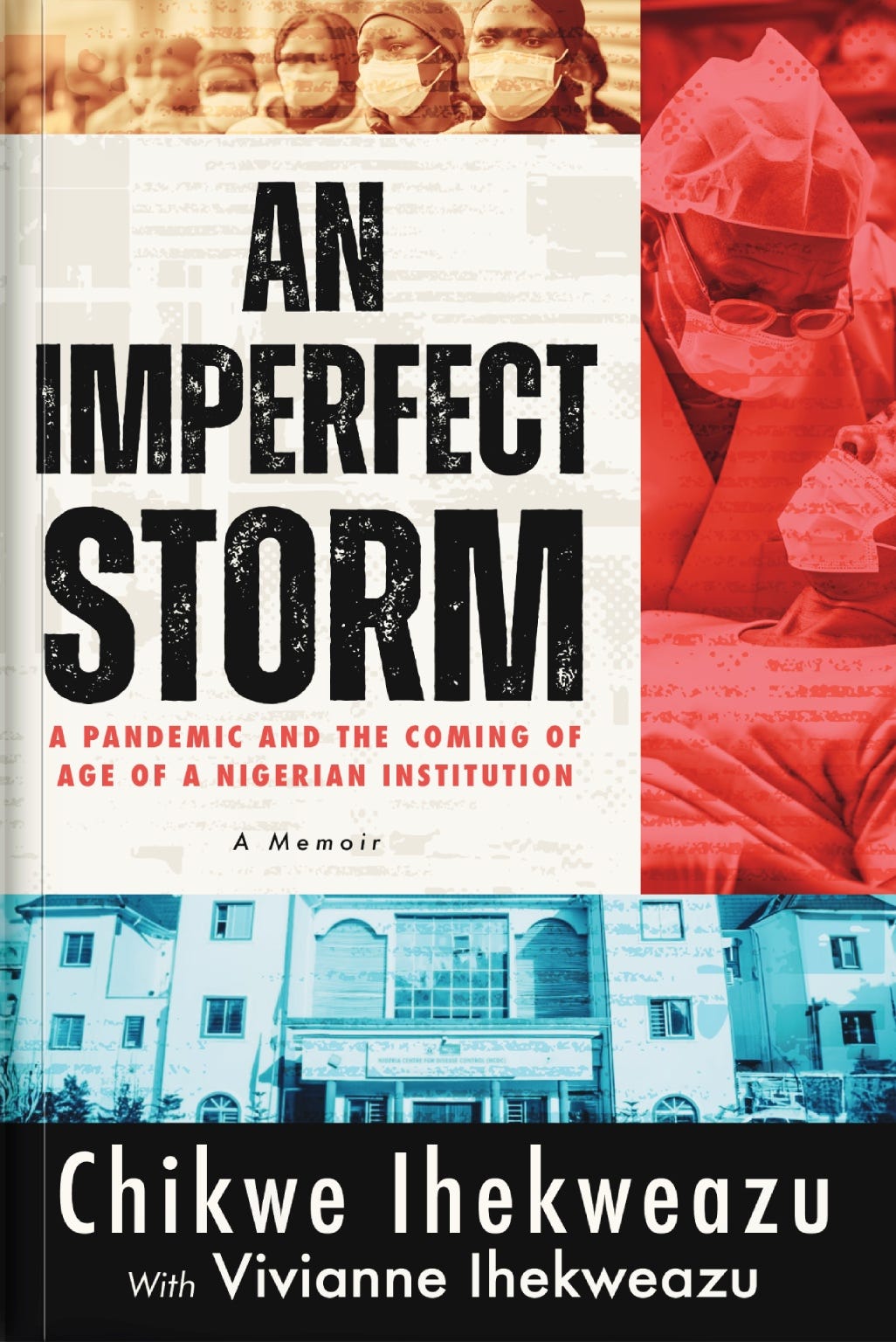

What we can learn from Chikwe Ihekweazu's memoirs 'An Imperfect Storm' and what comes after progress

If you ever get a random phone call telling you you’re now the head of a Nigerian government agency, congratulations—you’ve just won the Nigerian Meritocracy Lottery! In a country where offices are auctioned off to the highest bidder or the most connected crony, landing a role you didn’t ask for is the gold standard of "merit." Extra points if you and your family first hear about your appointment from the media. This was exactly how Dr. Chikwe Ihekweazu found himself, quite by surprise, as the Director General of the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) in August 2016.

Here’s another reason I know the appointment was based on merit: I first met Dr. Chikwe in London around 2012, back when he was organising TEDxEuston. Over a few meetings, I found him to be unfailingly polite, fiercely passionate about public health, and a thoroughgoing gentleman. So hearing that a good man entered public office and did good work is hardly breaking news. But what makes his memoirs worth reviewing? As it turns out, plenty. Meritocratic appointments, rare as they are in Nigeria, still happen, proving there’s hope for progress when qualified people step up. But here’s the real question: what happens after they leave office?

Dr. Chikwe Ihekweazu’s tenure at the NCDC was inevitably defined by the Covid-19 pandemic, which gripped the world in late 2019 and refused to let go for nearly three years. Nigeria had previously managed the 2014 Ebola outbreak with surprising success—a mix of good fortune and the right people in the right places. Yet, as he notes in his memoir: “One would think that our response to Ebola would have prompted the government to transform the country’s national public health institute in Abuja into a world-class agency; this didn’t happen.” Instead, when Covid-19 arrived, Nigeria was underprepared, facing not only this new crisis but also the ongoing health emergencies of Lassa fever and other endemic challenges. At the time, the NCDC had a mere 300 staff members, a third of whom were new recruits still in training and an annual budget of less than $1 million (N300 million back then). By contrast, the U.S. Centre for Disease Control (CDC) boasted over 50,000 employees, while the UK’s Health Security Agency (formerly Public Health England) had a workforce of 5,500. On top of all that, the NCDC had been set up without a legal mandate to guide its operations: the NCDC Bill would only be given assent by President Buhari in November 2018.

All of this meant that something as simple as getting all NCDC staff official NCDC email addresses was still to be done. A library was established from donated books and Nigerian researchers were integrated into the global body of published research to limit what is called in the jargon “parachute research“. NCDC got a website for the first time and began interacting with the public via social media. Small stuff you might say but everything needed to be built from the ground up and each one was very urgent. In confronting his first outbreak of meningitis in northern Nigeria, he describes scenes of children in Zamfara being treated under trees that passed for a hospital (the governor at the time, who lived 500 kilometres away in Abuja, described the outbreak as God’s wrath for the people’s sins). Even after obtaining help with testing from the US and WHO, it all came to nought when he realised that there was no national laboratory up to the task. Laboratories that had been donated to the Nigerian government in the past had fallen into complete disrepair. If ever there was a way to be unprepared to fight a pandemic, Nigeria was it.

Reading Dr. Ihekweazu’s account of Nigeria’s pandemic response feels like stepping into a time machine to a world we’ve collectively tried to erase from our memories. Remember when testing reagents were so scarce that they became a global treasure hunt? He recalls calling in personal favors to secure test kits and chemicals from the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) in Germany. The kits finally arrived in late January 2020—only for everyone to realise the wrong box had been shipped. After quickly pressing DHL into service, a week later, the correct test kits landed in Abuja. Dr. Ihekweazu, an international man of public health, reflects: “The true strengths of multilateralism and global collaboration were evident in our preparedness for the coronavirus outbreak in Nigeria. The support we received from WHO, Africa CDC and RKI at the early response stages were important catalysts as we prepared for our first case.” A sentiment that was easily overshadowed at the time and has been largely forgotten since.

In a grimly ironic twist, the arrival of Covid-19 in Nigeria during the peak of Lassa fever season (December to April) turned out to be something of an advantage. The disease, which Nigeria has been battling for over 50 years, meant the country was relatively well-stocked with protective equipment, and NCDC staff with outbreak response experience were already deployed across the nation. As Dr. Ihekweazu writes, “In the same week that Nigeria’s first Covid-19 case was eventually reported, we had 109 confirmed Lassa fever cases with eight deaths across 19 states.” The double crisis, though daunting, found Nigeria somewhat prepared—if only by misfortune’s peculiar logic. At 11:36 p.m. on February 27, 2020, Nigeria broke the news of its first confirmed Covid-19 case via a tweet. Less than a month later, on March 23, the first death from the virus was announced. In the chaotic interim, the President’s Chief of Staff, Abba Kyari—a polarising figure whose reputation I had reevaluated after meeting him in the UK months earlier—tested positive. This development sent shockwaves through the country, prompting urgent tests for President Buhari and his family. By April, Abba Kyari was dead, marking a grim milestone in Nigeria's battle with the pandemic.

Far more intriguing was the chaos unfolding behind the scenes as Nigeria scrambled to contain the virus, projecting authority and confidence from the shaky foundation of near-nonexistent state capacity. Governors and senior officials who caught the virus refused to disclose their diagnoses, for reasons best left to speculation. Meanwhile, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, bypassing the NCDC entirely, unveiled a new infectious diseases bill that dramatically expanded the Director General’s powers. The bill, however, quickly became a farce when it was revealed to be a near word-for-word copy of a Singapore law, with "Director General" appearing more frequently than "disease." Dr. Ihekweazu, unaware of its existence, suddenly found himself the target of public ire over the plagiarised proposal.

Other challenges bordered on the absurd. The NCDC, suddenly thrust into the spotlight, saw its phone lines—staffed by just 10 people—flooded with calls, ranging from pranksters to impossible demands for ambulances. Amid the chaos, Dettol Nigeria lent support by creating a public health advert featuring actress Funke Akindele, encouraging Nigerians to celebrate responsibly during Christmas and Salah. The goodwill was short-lived once videos emerged on social media showing that Akindele had hosted a party at her home in violation of public health guidelines. The NCDC found itself forced to play damage control—despite having no formal connection to her or the advert beyond Dettol’s involvement. Kogi State, sitting at the geographical crossroads of Nigeria and bordering nine other states, turned out to be an administrative minefield during the pandemic. Governor Yahaya Bello inexplicably declared the state "Covid-free," refused to cooperate with the NCDC, and famously avoided wearing face masks—except, of course, when meeting President Buhari. When the NCDC sent a response team to assist, the governor staged a theatrical rejection, live on television, deporting the team from the state. To add a twist of irony, he accused the NCDC of violating its own protocols by shaking hands without gloves and offered them a stark choice: either return to where they came from or endure a two-week quarantine in Kogi. Unsurprisingly, they chose the former.

Nigeria’s long-running struggles could only be overshadowed by the pandemic for so long. By October 2020, the #EndSARS protests erupted across the country, sparked by years of killings and harassment by the notoriously unaccountable Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) unit of the Nigerian Police. While the protests initially called for justice and reform, they eventually devolved into chaos, with widespread looting and arson. Warehouses became prime targets, fuelled by rumours of hoarded “Covid palliatives” meant for public distribution. One such warehouse belonging to the NCDC nearly fell victim to rioters, and it took personal appeals from Dr. Ihekweazu and his team to prevent it from being ransacked. Around the same time, an NCDC team on a supply delivery mission was ambushed by armed men, leading to the tragic death of Uche Njoku, a volunteer staff member who was shot during the attack. In another blow to the organisation, an NCDC staff member was found dead in his apartment after failing to report to work, though no foul play was suspected.

Amid these challenges, Dr. Ihekweazu faced a personal health crisis. Diagnosed with a serious medical condition in January 2020, he postponed urgent surgery for months to remain focused on managing the pandemic. It wasn’t until August that he finally underwent the procedure, a stark reminder of the personal sacrifices demanded by leadership during a crisis. The book’s final chapters, written by his wife Vivianne—a health professional in her own right—offer a poignant perspective on the toll his role took on their family. She writes movingly about balancing the demands of raising their two boys while supporting her husband, who had suddenly become the face of public health in Nigeria.

It’s been three years since Dr. Ihekweazu left his role as Director General of the NCDC to join the World Health Organization (WHO) in Berlin. Under his leadership, the NCDC transformed itself from a fledgling agency into a force to be reckoned with, expanding to 700 staff and forging robust partnerships with global public health institutions. More importantly, it cultivated a culture of dedication and purpose. Dr. Ihekweazu recalls the story of one staff member who began as a storekeeper and, with support and determination, earned a fully funded Master’s in Public Health at a South Korean university. From almost nothing, the NCDC became a name Nigerians could trust—a beacon of competence in times of crisis. Its presence offered reassurance that someone, somewhere, was working tirelessly to safeguard the nation’s health.

To paraphrase Napoleon: the NCDC’s achievements are granite—the teeth of envy are powerless against them.

For now, things are back to "normal" in Nigeria—but normal in Nigeria is anything but reassuring. Lassa fever has claimed hundreds of lives this year, while mPox continues to loom as a persistent threat. The pandemic severely disrupted the country’s immunisation programs, and there’s little evidence that Nigeria has fully caught up. Sourcing and funding vaccines remains an uphill battle. The country clings to donor-funded subsidised vaccine programs, not because it has the capacity to transition off them, but because ejecting Nigeria would be too embarrassing for everyone involved.

Yet I am left with several nagging questions about Nigeria after reading this book one of which is: how much is possible through the efforts of one person? Dr. Ihekweazu is generous in his praise of civil servants and the ordinary people tasked with the delivery of policies and programmes in the country. I am a bit more cynical than he is, I’m afraid. But I do subscribe to the idea that magic can happen if you have one good person in the right place at the right time. They can be a force for good and deliver positive change in a way that makes life that little bit more meaningful for millions of Nigerians across the country.

And what happens when they leave office? Ralph Waldo Emerson famously remarked that “an institution is the lengthened shadow of one man,” suggesting that individuals have the capacity to shape institutions with their vision and greatness. While this rings true in many contexts, it assumes a level of permanence and responsibility that Nigeria’s institutions often fail to deliver. In Nigeria, institutions frequently resist the influence of even the most determined leaders, stubbornly reverting to a zero state once that individual departs. It’s a dynamic Emerson likely didn’t foresee—a reality where institutions are less a reflection of leadership and more a testament to their own refusal to be institutionalised.

I shouldn’t be so cynical. Dr. Ihekweazu is a good man, and Nigeria is undeniably better off for his service during such a critical moment. The lessons of the pandemic are still unfolding globally, but the world’s response—riddled with errors and hysteria—has prompted many countries to quietly sweep it under the rug, pretending it never happened. In this context, much of Nigeria’s pandemic experience and its aftermath, as a country on the receiving end of the virus, is far from unique.

The most pressing question for me is this: how is progress sustained in a country like Nigeria? We know progress is possible—countless examples prove it. We know there are good people—finding them isn’t the challenge. What remains uncertain is whether something good and progressive today can withstand the forces of inertia, apathy, or regression to remain so tomorrow. Progress, after all, isn’t self-sustaining; it requires vigilance, effort, and systems strong enough to outlive the individuals who create it.

An Imperfect Storm is published by Masobe Books and is available from all good bookstores.

Thank you for writing this. It was a blessing we had him at the helm at that time 🙏

Great piece. Naira equivalent in 2019 should be ~300mill not 180.