A Hard Nut to Crack

Even if the export ban doesn't work, there is no need to go nuts over shea

Of all the instruments in the Nigerian economic policymaker’s arsenal, the ban is surely the bluntest and most familiar. Anytime one hears an announcement from Abuja, you instinctively brace for the usual protectionist measure: another import prohibition in the name of some nascent industry. Yet the ban issued yesterday from the State House gives me pause: President Tinubu has not banned the entry of a foreign good, but the exit of a native one: the raw shea nut:

President Bola Ahmed Tinubu has approved a 6-month temporary ban on the export of raw shea nut to curb informal trade, boost local processing, protect and grow Nigeria’s shea industry.

The ban, which is with immediate effect, is subject to review on expiration and specifically aimed at boosting Nigeria’s shea value chain to generate around $300 million annually in the short term.

If nothing else, this departure from the usual opens up the possibility of a fun six-month experiment we can all watch keenly together.

The case for the ban

The core rationale for the ban, as presented by the government, rests on a stark economic discrepancy. To be clear, these are not my arguments but the case put forward by authorities, which I have seen and I am merely presenting here. They contend that Nigeria is the world’s largest producer of shea nuts, accounting for an estimated forty percent of the global supply, yet its financial return from this dominant position is negligible, capturing less than one percent of the multi-billion dollar global export market. In essence, the country is said to export raw volume, not refined value, forgoing the significant revenue that comes from processing.

This underperformance is attributed to two primary leaks in the value chain. First, a substantial but informal cross-border trade funnels raw nuts out of the country before they can be domestically processed. Second, this external drain exacerbates a critical shortage of raw materials for local processors, who report operating at half their capacity. The financial incentive to change this is clear: exported shea butter earns four times the value of raw nuts, while more refined derivatives like stearin - a cocoa butter equivalent (CBE) used in chocolates and bakery fats - can command a 10x premium.

The situation is further compounded by regional policy shifts. Neighbouring shea-producing nations, including Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, Mali, Togo and Ghana, have already instituted their own bans on exporting raw nuts. This has had the effect of redirecting international buyers towards Nigeria as the last major open market, intensifying competition for the commodity and allowing them to outbid local processors at the source. The result is a critical supply shortfall that disrupts factory operations and causes missed export contracts for higher-value goods.

In response, the policy is conceived as an immediate intervention to secure domestic supply. By halting the export of raw nuts, the stated aim is to channel the entire harvest towards local processing facilities, boosting their utilisation rates and shifting the national export profile from raw materials to refined products. Success, by the government’s projection, would see exports become nearly entirely processed and generate hundreds of millions annually, preventing further factory closures and capturing the value that has, until now, been lost.

It is worth noting that this is hardly Nigeria's first rodeo with export bans. As detailed in a 2024 WTO Trade Policy Review (PDF, page 52), the country has long maintained prohibitions on items like maize, timber, and scrap metals, primarily to address domestic supply shortages, curb vandalism or protect natural resources. The shea nut ban, however, represents a different and more interesting policy experiment. Its primary objective is to forcibly catalyse a domestic value-added industry, making it a distinct and arguably more ambitious use of the export prohibition tool.

Shea nuts, a quick primer

To understand the stakes of this ban, one must first understand the shea nut itself. The shea tree, Vitellaria paradoxa, is a very slow-growing cornerstone of the African savannah, incapable of being rushed. A tree does not bear its first fruit until it is at least ten to fifteen years old, only reaching fuller yields after two or three decades. With a lifespan stretching up to three centuries, these mostly wild-harvested trees represent a natural long-term investment, making supply inherently inelastic and impossible to quickly scale.

The harvest and processing of shea is a women's domain. Across Africa, an estimated 16 million rural women are the backbone of the shea economy. The traditional method of producing shea butter is a labour-intensive, multi-day process of gathering, boiling, drying, shelling, roasting, and hand-kneading the kernels to extract the prized fat. Industrial processing, by contrast, uses mechanical pressing and solvent extraction to produce refined butters and fractionate them into solid stearin and liquid olein, each with distinct properties and uses.

West African shea, higher in stearic acid, is a key component in cocoa butter equivalents (CBEs), vital to the global chocolate and confectionery industry. In fact, a counter-intuitive but critical industry fact is that despite its "cosmetics image," an estimated 85-90% of exported shea ends up in food applications (PDF, page 9), not face creams. Its value extends to by-products like shea cake, used for fuel and animal feed, illustrating a complex and versatile commodity chain.

Should you try this at home?

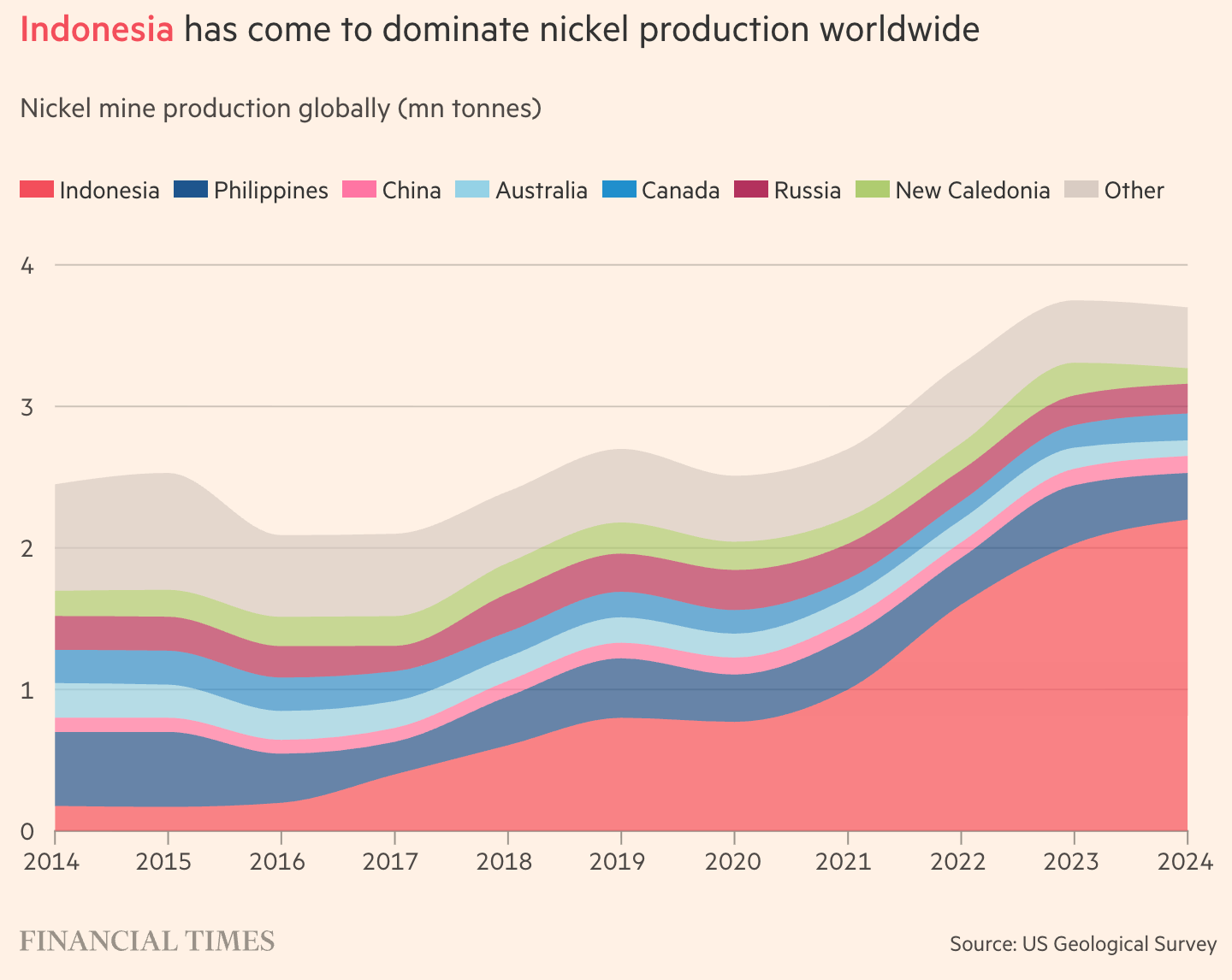

The most salient recent example of an export ban on a raw material is Indonesia’s nickel policy. For any government considering a similar path, its story is both a blueprint and a cautionary tale.

In 2014, Indonesia first banned exports of nickel ore to force domestic processing, though it partially relaxed the rules in 2017. The policy found its teeth with a full, decisive re-imposition from January 2020. Despite a successful legal challenge by the EU at the WTO, Indonesia appealed into a voided process and held its course. The credibility of this threat was that it forced any market participant who wanted access to Indonesian nickel to build smelting capacity within its borders.

The strategy succeeded, surprisingly to many, for a number of reasons. Chinese industrial giants, led by Tsingshan, responded with tens of billions of dollars in investment, bringing technology, capital, and guaranteed offtake agreements for China’s stainless steel and electric vehicle battery supply chains. This was facilitated by ‘plug-and-play’ industrial parks with captive coal power and aggressive fiscal incentives, including multi-year corporate tax holidays. Critically, process innovation (you know this is one of my favourite words right?) cracked the code on converting Indonesia's specific type of nickel into battery-grade material, pivoting the entire operation into the high-growth EV sector. The government’s entire apparatus was focused on a single objective: build downstream capacity in-country.

The results in the data are undeniable. Indonesia’s share of global refined nickel production surged, and it now accounts for the overwhelming majority of global supply growth. It transformed from a mere miner of ore to a dominant power in refined metal, even gaining approval for its brands on the London Metal Exchange.

However, this ‘success’ has come with significant costs that define its current reality. The flood of new supply has created a global surplus, hammering nickel prices and squeezing producers worldwide, including less competitive Indonesian smelters. The strategy has also led to a profound dependency, with roughly three-quarters of the country’s refining capacity now under Chinese control. Furthermore, the breakneck development has a severe environmental price, reliant on coal-fired power and drawing scrutiny for waste violations, which is now triggering tighter regulatory reviews and raising future compliance costs.

Indonesia’s nickel ban, therefore, “worked” in the narrowest industrial-policy sense: it built a downstream processing sector at scale, attracted immense foreign capital and technology, and catapulted the nation to become the world’s swing supplier. The reward for this audacious policy is undeniable market dominance. The bill, however, includes profound dependence on foreign operators, severe environmental exposure, and a market bust triggered by its own success. Whether this constitutes a model depends entirely on a nation’s appetite for such trade-offs and, crucially, its capacity to secure the anchor investments that can transform a ban from a blunt instrument into a functioning industrial reality.

To state the obvious: shea nuts are not nickel. No vast, hungry electric vehicle battery supply chain awaits its output, and no foreign power is compelled to underwrite Nigeria’s industrialisation for the simple reason that no one is putting shea butter in a battery. China’s strategic imperative, which proved so decisive in Indonesia, simply does not apply here. The critical, unanswered question therefore remains: from where will the investment come? If Nigeria intends to follow this playbook, its success hinges on its ability to seek out and secure committed partners from a far more fragmented global market - whoever and wherever they may be.

Start the clock

All of this leaves me in a suspended state of judgement. Despite my instinctive aversion to trade bans, this particular intervention is “interesting.” The logic is somewhat coherent, the regional context justifies a defensive response, and the potential upside is tangible. Yet, a host of practical questions remain. Is a six-month timeline sufficient to build the aggregation hubs and attract the necessary investment, or is it merely a political gesture? Given Nigeria’s notorious customs enforcement, can the ban even be policed effectively, or will it simply distort the informal trade without capturing the value?

Furthermore, the immediate economic dislocations cannot be ignored. With recent annual exports valued around $15 million, who will compensate the countless smallholder farmers and aggregators for the sudden loss of this badly needed foreign exchange? And with the smuggling routes to neighbouring countries largely closed by their own bans, will local processors, now endowed with monopsony power, simply shaft the farmers, knowing they have nowhere else to go?

Ultimately, this policy presents a fascinating, and thankfully contained, experiment. Shea nuts are not crude oil; the sector’s fortunes will not make or break the national economy. If the ban fails, the damage will be limited. But if it succeeds, it could provide a replicable template for capturing more value from other raw commodities. It is for this reason that I’m choosing instead to sit on the fence. I will be paying attention to the implementation, the market response, and the real-world impact on the women who gather the nuts.

See you in six months.

Well in the words of a wise sage 'the propensity of the manhood to attain turgidity or otherwise does not rest in the physical strength of the man carrying it but in other less obvious attributes'. While there seems to be a case for a ban, it feels to me like another one of our whack-a-mole policy interventions. I would have expected that other follow up interventions/incentives would have been put in place to ensure its success but going by just your article here, it seems that has not happened? And if Niger has not 'banned' the export, doesn't that open a viable route for the exportation to just continue via the already existing informal networks in a manner similar to the unfettered flow of refined fuel during the subsidy years? But then we are Nigeria; learning is not exactly our forte.

Apparently, a couple of companies have already set up processing plants, viz Salid Agriculture (https://salidagriculture.com/) and TGI (the CHI Farms guys). However, they are starved of raw material to enable them run at full capacity. But you raise valid concerns about their new-found monopsony power. Also, considering how porous our borders are, will this ban be enforced?

We wait to find out.